Many picture books aim to spur conversation around the quirks of English spelling, but Beth Anderson’s An Inconvenient Alphabet is a class above. While alphabet books like the popular P Is for Pterodactyl highlight unconventional spellings without illuminating the why’s behind them, An Inconvenient Alphabet goes much deeper. It brings to life some of the history and power dynamics responsible for English spelling—in ways that intrigue adults and children alike.

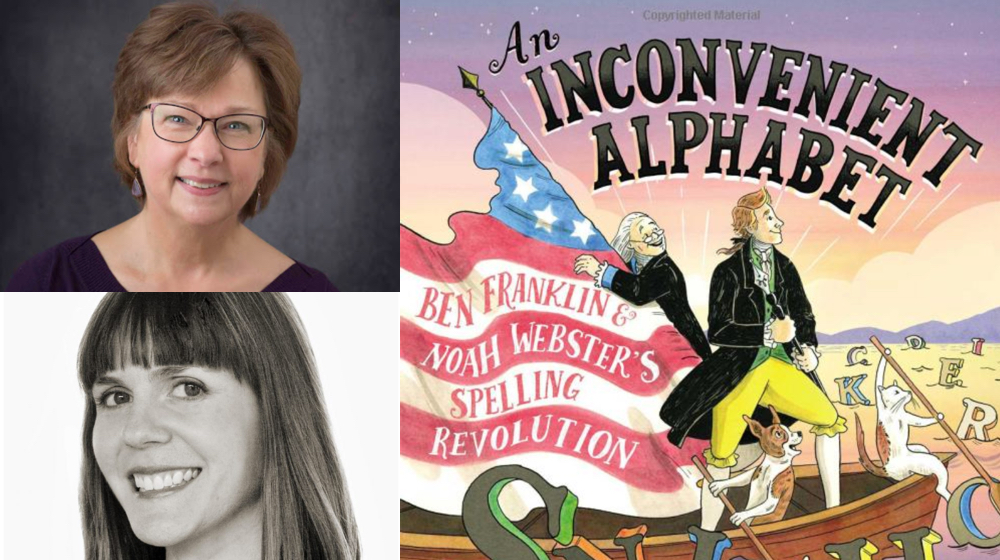

The book explores the true story of Ben Franklin and Noah Webster’s shared belief that English has letters with too many sounds (think: the various g sounds in goat, giraffe, and laugh), sounds with too many letters (the k sound in chorus, kite, cat, and quiet), and some letters that just aren’t needed at all (the silent letters in lamb, walk, knock, give). The bright, energetic marriage of text and illustration powerfully presents their efforts to revamp spelling in the service of American unity, identity, and clear communication.

Letters themselves, the 26 we know plus others Franklin created that never took off, are important characters in the book. Designed to represent the sounds aw, uh, edh, ing, ish and eth, Franklin’s new letters are depicted as 3D models carried around in a sack and handed out for examination. When I read the book with my daughter, she anticipated objections to the new letters—they look funny, would be tough to learn, and would make old books harder to read.

Illustrated with color, movement, and flair, the lively letters heighten the smart, inventive book’s explanatory power. Kids can see the oddity of the proposed letters, as well as the resistance in the faces of townspeople when Franklin shares them.

When Franklin’s introduction of new letters flops, the book moves on to Webster—the founder of the famous dictionary. It recounts his attempts (and mostly failures) to make English spelling more phonetic by advocating for using existing letters differently. Namely, he pushed for getting rid of silent letters (thum vs. thumb), plus using one vowel for short sounds (hed vs. head) and two for long ones (seet vs. seat). We read about how a few of his changes were adopted in fits and starts, and others rejected wholesale.

“Next time you sound out a word, think of Ben and Noah,” the book concludes. “THAY WUD BEE PLEEZ’D BEECUZ THAT IZ EGZAKTELEE WUT THAY WONTED!”

Informative and funny, An Inconvenient Alphabet shows how English spelling represents much more than letter-sound correspondences. Letter sequences, it reveals, embody choices that people and publishers have made, based on their own accents, understanding, and ideas about the value of tradition.

And people’s resistance to purely phonetic spelling has something to teach also: that history and meaning matter—and old (spelling) habits die hard.

Do you think English spelling should be made more phonetic? If so, why? And whose pronunciation would you use as the model, given the range of English pronunciations around the world?

Sources and Further Reading

Treiman, Rebecca, “Teaching and Learning Spelling,” Child Development Perspectives 12, 4 (2018): 235-239.

Treiman, Rebecca, “Statistical Learning and Spelling,” Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools 49 (2018): 644-652.

Sliter, L., “Cough, Cough: Here Are 10 Different Ways To Say ‘ough’,” Dictionary.com Everything After Z, accessed February 7, 2019, https://www.dictionary.com/e/s/ough/.

Treiman, Rebecca, and Brett Kessler, Kelly Boland, Hayley Clocksin, and Zhengdao Chen, “Statistical Learning and Spelling: Older Prephonological Spellers Produce More Wordlike Spellings Than Younger Prephonological Spellers,” Child Development, 89, 4 (August 2018): e431-e443.

Doyle, A., J. Zhang, and C. Mattatall, “Spelling Instruction in the Primary Grades: Teachers’ Beliefs, Practices, and Concerns,” Reading Horizons 54 (2015): 1–34.

Fresch, M. J., “A National Survey of Spelling Instruction: Investigating Teachers’ Beliefs and Practice,” J. Lit. Res. 35 (2003): 819–848.

Jones, A. C. et al, “Beyond the Rainbow: Retrieval Practice Leads to Better Spelling than does Rainbow Writing,” Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28 (2016): 385–400.