I’m reminded of my dad as I watch the #banbossy and #bossyandproud hashtags fly on Twitter. He was committed to cultivating my leadership potential and I’m sure that if he were still alive, he would be on Team Bossy and Proud. More importantly, he would expect me to have my own opinion on the subject and to put forth a well-reasoned defense of my view, whether I agreed with him or not. He was that kind of a father–and lawyer.

Team Ban Bossy led by Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook COO and “Lean In” author, posits that the term “bossy” is disproportionately applied to girls and inhibits their leadership aspirations. Her BanBossy.com website, launched in conjunction with the Girl Scouts of the USA, offers tips and tools for fostering ambition in girls.

While the literal notion of outlawing the word “bossy” is absurd, the underlying call to be conscious and intentional in the labels we apply to ourselves and others is spot on. As the mother of a daughter, the spirit of the Ban Bossy campaign resonates with me. Upon hearing of it, I immediately (and only half jokingly) began referring to my 2-year-old’s incessant demands as “displays of executive leadership potential,” instead of something less complimentary. So, hat tip to Sandberg and the Girl Scouts for raising the issue of gender bias in a catchy enough way to engage the public.

I also applaud Sandberg’s campaign for providing practical activities, worksheets and talking points that parents can use to groom their daughters to lead. In them, I see many things that my dad did with me through the years. He didn’t need a Ban Bossy manual to tell him to use role-playing to impart skills that I would need to navigate tough conversations. He was a leadership training natural. From elementary school mock trials in our living room to salary negotiation drills after high school, he was constantly filling my toolkit of practical strategies for advocating for myself and others.

But as a smart, ambitious black man born in 1944, he had an edge to him that was sharpened by years of combating and overcoming racial discrimination. And that edge informed his worldview and parenting style. He was forceful and determined (read: bossy) in teaching me to be excellent and uncompromising, because experience taught him that was an effective way for black people to command respect in a world unwilling to freely offer it.

I am my father’s daughter and in 2014 I suspect that “bossy” is the least of the epithets my daughter Zora may face. Moreover, I’m convinced that she may need all the insistence and assertiveness that the word implies to thrive. That’s not to say that I don’t want her to be kind and generous. I do and she is. But when it’s time to lead (and when isn’t it?), I would prefer for her to err on the side of dominance than submissiveness. That’s real talk.

I would want her to proclaim, like bell hooks, the feminist/activist/scholar who launched the Bossy and Proud of It countermovement: “I will not have my life narrowed down. I will not bow down to somebody else’s whim or to someone else’s ignorance.”

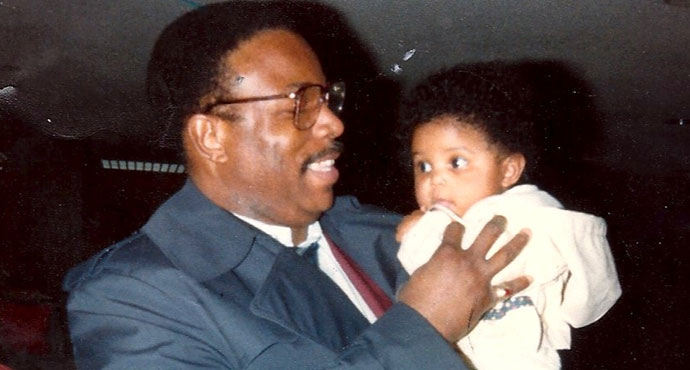

My dad taught this kind of mettle by example and lecture, but also through story. He was a wonderful tale teller with a rich voice and a commanding presence. He punctuated insights with dramatic pauses, wooed audiences (whether a jury or his pint-sized daughter) with well-timed zingers and worked every inch of the stage (and, believe me, anywhere he stood became his personal platform).

As a city prosecutor, using those rhetorical devices in closing arguments won him the nickname Jury Jim. At home, holding court before me, his only child, those dramatic flourishes won my lifelong admiration.

Most of his stories seemed to emerge spontaneously, but one–the chronicle of his career–was well-rehearsed. The speech originated as a part of a youth motivational task force that dispatched speakers to schools around town to inspire academic achievement and lifelong success in kids. But he happily gave encore presentations to my classes and youth groups whenever I asked.

Wearing a suit and tie, wire-rimmed glasses and a broad smile, he regaled us with stories from his youth. Notably, he drew straight lines from his bossy, argumentative childhood to his career success in adulthood. Playing little dictator and ruling over three siblings who were a decade his junior? Preamble to business school. General mouthy impudence? He made it sound like early LSAT prep.

And I listened, rapt, year after year, to this origin story of a mythic figure in my life. Having no siblings of my own, I sought out opportunities to boss, er, lead other kids everywhere I could–the local NAACP Youth Council chapter, student council, PEACE (People Encouraging the Acceptance of Cultures Everywhere) and other groups. In high school I announced my plan to get a joint JD/MBA from Harvard.

My dad was the model parent described by Rachel Simmons, co-founder of the Girls Leadership Institute, in the Ban Bossy parent’s guide: “Caregivers who celebrate their girls’ assertiveness can buffer them against the culture’s mixed, sometimes toxic messages about girls’ personal authority and power. What we say matters as much as what we do.” He built me up, loudly and proudly.

I want to do the same for my daughter and I think nurturing a little edge, or “vinegar” as my husband calls it, may help. I bet time, experience and practicality will slough off any counterproductive pushiness in her. I know that the bigger threat to her leadership development is failing to build sufficient confidence and conviction in herself in the first place. So, advantage: Team Bossy and Proud.