Do you ever wish you had a fairy godmother to get you through the tough moments of parenting? Or maybe a magic wand?

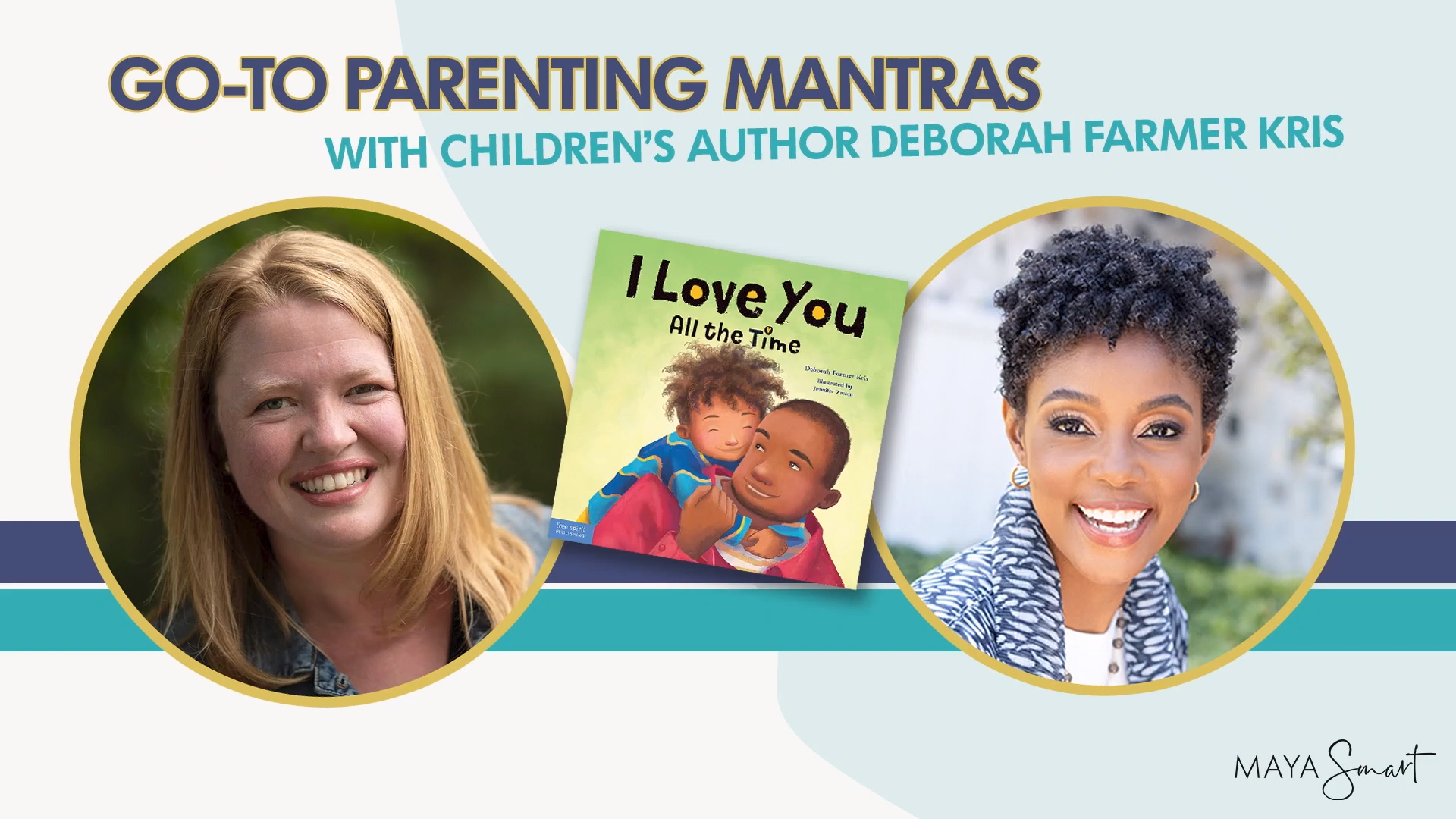

Parenting author Deborah Farmer Kris shares how parenting mantras can work like magic for parents when they’re at their wits’ end—how remembering a key phrase can rescue the moment when we’re in deep.

In this interview, she reveals:

- What to say to kids, from toddlers to teens, when they’re stressed

- How to handle children’s meltdowns with six little words

- The single lowest-effort, highest-return thing you can do for your child

As a parent, an author, and an advocate, I’ve found Deborah’s insights illuminating and her advice inspiring. She’s the founder of Parenthood365, author of a powerful line of children’s books, and a parenting writer for outlets like PBS KIDS for Parents and NPR learning blog MindShift.

That’s why I wanted to chat with her about raising kids, and share our conversation with you. I know I’ll keep some of her tips on turning challenging moments with children into transformative ones in my toolbox for use for years to come. If you want to learn some of Deborah’s favorite parenting mantras—plus get inspired to create your own—hit play or scroll down for a transcript of our conversation.

Maya Smart: I'm so excited to be here today with Deborah Farmer Kris, who has worn many hats as a mother, a writer, a parent educator, a teacher, a school administrator, and much more. Can you tell us a bit just about your journey into writing and parent education and also children's literature now?

Deborah Farmer Kris:

I had my first child in 2011 and I began to realize that as much as I just adore working with kids, and I still do—I was trained as an educator—and parenting was still really hard. I was trained in child development. I was steeped in this, and still when my kid would have a meltdown at Target, it just triggers all of your anxieties. And I thought, there’s so many amazing, wonderful, loving parents who don’t have all this training, and that must be… What can we be doing to support each other? And so that’s where I began to get really interested in parent education. And then I decided a couple years ago to write some picture books for kids, which we can talk more about later.

Maya Smart: Tell us a little bit about the process you discovered for translating some of the research and theoretical things that you had learned into actually, in the moment, doing the right thing with your child.

Deborah Farmer Kris:

Well, it really—honestly, the process of writing about it has really, really helped. Because I read everything. I’m a bit of a compulsive student, and so I read lots of articles and books, and like you, I talk to a lot of people. And then when I sit down to, say, write the article for PBS Kids for Parents, I try to think, okay, what are the two nuggets here? Of everything I read, I know that our working memory can only take in so much. What are the two or three nuggets? And then I often think about, okay, so what does that sound like in the moment?

So, let’s say we’re talking about trying to help our kids understand their emotions, or let’s say that they’re hitting their sibling. What might more responsive parenting sound like? And so, practicing the script. And then I would say, all right, so I have to try this myself. It got to the point where I’d practice it so much, it became part of my internal script.

And one of the things that, when I’m working with parents, that I have to emphasize is that it’s never a quick fix. Parenting is a long game. And your child, there’s no cookie cutter. There’s no vending machine where you put in something and out comes your Twix bar. It may work great one day, and the next day you use the exact same script, and it just falls flat. Which is why just feeling like you have a lot of tools, and not just for talking to your kids, but for talking to yourself… What are my go-to things for talking myself down when I’m feeling like crappy parent, or I’m feeling like I don’t have it in me, or I’m triggered by my child’s insecurity that day, because it’s triggering something deep from my childhood, what are my own self-care tools that I am practicing over and over again?

I have a dear friend who has a child who’s been going through a lot of struggles. And she’s the one who said to me, “I just keep telling myself it’s the long game.” And that has become one of my parenting mantras, is that one of the joys of having worked with kindergarten through 12th grade, I work a lot with college seniors, is you see them as fourth graders, and you see them as awkward middle-school students, and their parents are freaking out because their cute 10-year-old is now a very hormonal, sassy 14-year-old, and then you see them as seniors, and you see, okay, this is such the long game. Everything we’re putting into it, none of it’s wasted. All these conversations, all these books that you read to them when they were one-year-olds, that’s not wasted for their literacy when they’re five. And all the conversations you’re having when they’re 9-year-olds about tough stuff are not wasted when you can have a conversation when they’re 15, and the stakes are higher.

Maya Smart: I love this idea of having go-to mantras, both things that you say to your child when certain situations arise, whether they're having a meltdown or some other situation, but then also having go-to mantras or touchstones that you return to for yourself. Do you recommend that people write those out in a journal, or how do they instill the habit of thinking those things?

Deborah Farmer Kris:

I think it’s helpful, whatever your system is, right? Whether it’s helpful to write it down, put it on a sticky. For me, my writing mantra is “tell the story of hope,” and it’s on a sticky note and it’s by my desk. It’s pinned to the top of my Twitter feed, so I see it every time I go there. Because for me, that’s motivating to me, is that we live in a really, sometimes, very scary world. And every time I write an article or write for parents, I think about, how do I tell the story of hope? So if a parent is searching for this because their child is having tremendous anxiety, and so they’re searching out my interview with Lisa Damour about this topic, I want them to leave feeling like hope isn’t… It’s not wishful thinking. It’s not toxic positivity, but it’s real. And that’s a good thing to have.

So sometimes I literally write them down, and sometimes there have been phrases somebody has shared with me that are so good, they just get sticky in my brain. And I’ll share one of them with you that I use with teenagers all the time. And this one actually comes from Lisa Damour’s book, Under Pressure, where she talks about, the real concern is not whether or not your child is stressed out, because they will be, and that’s okay. It’s what are the strategies they’re using to cope with that stress. So are they turning to substance use? Are they turning to self harm? What are the strategies they have?

And so, rather than jumping in to trying to solve it, this phrase, which is just like magic, is: “That sounds tough. How do you want to handle it?” Or: “That stinks. How do you want to handle it?” And that honestly is a great mantra for myself too. So it’s like, okay. The situation stinks. How am I going to handle this?

Because it communicates to kids two things at once. One, empathy. This is a tough situation. But two, confidence. I trust your ability to figure this out, and I’m standing right here by you. And I have had a couple of moments where I’ve been mentoring a high school student. We’ve been going on a walk around the block, and literally every five minutes, they’ll finish something, and I’ll say, “Oh yeah, that’s rough. How do you want to handle this?” And that’s literally almost the only thing I say. And at the end, they’ve solved their own problems, and they thank me for doing—nothing other than listening.

And I feel like that is one of those great core phrases that sometimes I just hear and say, “That’s going to work.” And that may be not the core phrase you choose to use, but I look for those when I’m reading somebody. Like, okay, that one for my child, for my students, I think that one might work. That fits my personality. I’m going to try it and make it my own.

Maya Smart: I also have a 10-year-old, or a child born in 2011, and I definitely will try that phrase out. Because there are almost daily situations with friendship or on the sports field or in other situations where, as a parent, you want to offer a solution and give a specific bit of that, well, you should say this or you should do this. But I love that idea of just stepping back and empathizing with, yes, that's a tough situation. That's tough, but how do you want to handle it? I think it also implies that they have some choices, and they can think through all the different things that come to mind for how they might handle it, and then proactively make a choice that makes sense for them in that moment. Would you also say, when they respond with a way of handling it that isn't how you would've recommended, how do you follow up? How do you pause and not correct or change what they've responded with?

Deborah Farmer Kris:

That’s a great question. I’ll go to the high schoolers I work with, because this is… For anybody you have who has a high school audience, sometimes I just ask, “If you could wave a magic wand and solve the situation, what would be… What would you hope it would come out of it?” And then if there… First of all, if it’s not something that’s going to necessarily hurt anybody, they can try it. And if it fails, they try something else. I don’t want to undermine their ability to test something else, because trial and error is a huge part of, just, emotional growth. But if their instinct is to be like, “I’m going to go tell that teacher off,” then I’ll say, “Okay, but what do you want the ultimate outcome to be? Well, if you want to still have a good relationship with that teacher, is this going to help get you there?” And so it’s more of that—coaching questions.

But the idea being the coach versus the problem solver. It’s so easy to say this when you’re writing the article. It’s so much harder in the moment because you’re thinking, “I’ve been here. I can solve your problem.” But it’s really undermining for kids and for their… Even just for their own, not only their growth, but for their anxiety, if we’re constantly stepping in, saying, “This is how to handle it. This is how to handle it.” Because I think it reflects that I can’t do this without my mom or dad. I can’t do this without my teacher. And we want them ultimately to be able to do it without us. With our love, with our support, but with the confidence they can do it on their own.

Maya Smart: Another thing I've gained from reading your work, both in children's literature, and then also through your columns, is this idea of I love you all the time as a mantra or something that parents can just have as a go-to. And I can imagine that phrase being used with a toddler who's had a meltdown, and you're responding to that. I love you, but I'd like to maybe see a different behavior. But then also, as you mentioned with the teenager who's having some more complicated problems and maybe making choices that aren't necessarily the ones that you would make as an adult who's lived through some of that trial and error that they have up ahead. But can you tell us a bit about the inspiration for this book, I Love You All the Time, and the message that it sends to children through parents?

Deborah Farmer Kris:

So that is my ultimate parenting mantra. That is the one. And the background on that is really when my daughter was a two-year-old and she was having just an epic meltdown, and I was trying everything in my repertoire to calm her down. It wasn’t working. And I finally, I scooped her up, and I put her on my lap. And we were rocking, and she was fighting me. And I said to her, “I really love you when you’re mad.” And she stopped crying. And she looked at me like I was nuts. And so I kept going, and I said, “I love you when you’re happy. I love you when you’re sad. I love you when you’re scared. I love you when you’re mad, I love you all the time.”

And she settled down. And I realized that that was, I think, such a core question that so many of us have about our own selves, even as adults, of will I still be loved if I don’t do this. And I think for kids who have these big, overwhelming feelings or are getting lots of constructive feedback, let’s say you have a child who is neurodivergent, who they’re getting constant feedback at school about… “Where are your shoes? Where’s your assignment? Where’s this? Pay attention.” Just to be… That feeling that Mr. Rogers gave those of us of that generation, who watched him and could hear him say, “I love you just the way you are.”

So that became my nighttime ritual with my kids, is that I would say that. “I love you when you’re happy. I love you when you’re sad. I love you when you’re scared. I love you when you’re mad. I love you all the time.”

And my son, when he got a little older, would start pushing on that. And he would say things like, “What if I chopped down your favorite tree? What if I punched you? Would you still love me?” And it was this awesome opportunity to talk through, “I wouldn’t be happy that you hit me, but I would still love you.” That love is the common baseline.

And I think it reminds me that in so much of parenting, there are things that we assume our kids know. And I think so much of parenting is making the implicit explicit. So the things that we think that they understand, from issues of how to be polite and say please and thank you, how to write a thank you card, to issues of race and class in America. We might assume they’ve just picked it up, but we have to be able to talk in an open way. And so for me, being able to say “I love you all the time,” that’s my mantra. Then that’s the baseline where we can have every other conversation, every other important conversation.

So after about seven years, I decided, hey, that’s a picture book, so I turned it into one. Free Spirit accepted it and then said, “Could you turn into a series?” And that’s how the All the Time series came about.

Maya Smart: And what was it like for you, transitioning from writing for parents to writing for children?

Deborah Farmer Kris:

Well, the great part about writing for Free Spirit is that at the back of the book, there’s a letter to caregivers, which is one reason I really want to work with them, is because my thought was, one of the most amazing moments for me as a parent, there’s nothing I love more than read aloud. I’ve read to my kids every day since they were born. They’re 8 and 10 now. It’s just part of our daily routine. And I thought, there are a lot of parents for whom they may not be reading the parenting book, but hopefully they’re still sitting and reading to their kid. And so, all of these books are written from a caregiver’s voice writing to a child—sorry, speaking to a child. And so, I thought I’d love to be able to just almost facilitate that moment between a caregiver and a child, where in reading this book, there was that practice with the language, but also just that sense of closeness that can come.

And so, the best part is that my kids could be beta testers on a book like this, and I’ve read so many thousands of books, not only to my own kids, but as an elementary school teacher, that getting the rhythm right was really important to me. Getting the pictures, art direction right was really important because I just know what read-aloud can be. And so do you, with all of your work on reading, that it feels—much more so than even my other writing for publications—this feels like, almost, the sacred-trust writing, because you’re writing something that is read aloud to a child. And that, to me, it’s just absolute magic that I’ve had a chance to do it. And I’m super excited to do more of it.

Maya Smart: I love this idea that the book itself contains a lesson for parents. There are so many wonderful children's books, and, as parents, we choose them for all different reasons. Sometimes we love more of the story, or we love the illustrations, or there's some other feature of the book that we love. And sometimes, books—the author's intent for how the book will be read and what it can teach are different than the parents' ideas. So I love this idea of books that are explicitly written in the parents' voice and books that contain a couple of pages of notes or a letter to the parent, telling them how best to apply some of the themes of the book in everyday life with the child. But I love the phrase that you use also, just facilitating a moment with children. What advice do you have for parents, as someone who has read hundreds of books now, or hundreds of stories? What advice would you have for a parent who has not yet instilled that habit, or perhaps doesn't see the value in it?

Deborah Farmer Kris:

It’s the most rewarding, high-benefits, low-effort thing you can do to influence your child, in the sense that you can go and get some books at the library, zero cost, sit down. And every time you read a book to your child, you know you are helping them. You know that moment, one, is developing a relationship with books, because they’re associating books with the moment of closeness with their parent. They’re getting just the sense, the rhythm of the story, the context clues. And so, I know especially when COVID just started and there was so much concern about how do we do this at home? And my thought is, if we do nothing else but sit and read to our kids, the research is so profound that children who are read to are those who become stronger readers.

And it’s not… And I think so much of that is just even the emotional connection with books, that you remember the lilt of a person’s voice, your grandmother sitting and reading a favorite book, and sitting on the lap and having that closeness. And, for me, I do mostly read aloud at bedtime. And so, it’s one of those ways where even if the evening really didn’t go well, there’s a moment of closeness at the end of the day. Pick one book off the shelf. Often, it’s an old favorite. We’ll sit, we can read one book, and you end the day feeling connected.

But I remember, my second book is You Have Feelings All the Time. And before I wrote that, I remember there was a day when my son was about four, and he was just having a terrible evening. And I had lost my patience. He had lost his. And finally, I was like, “Go get yourself a book.” Because I always read a book. And he went over to a shelf, and he pulled out Glad Monster, Sad Monster, which is a feelings book.

And he brought it over. And I read it, and I actually got teary while I was reading it. And I looked at him and I said, “Are you having a lot of big feelings today?” He just—his eyes got big and he nodded. And I thought, that book provided this moment where it allowed him to communicate what he was struggling to communicate. His emotions, his behavior was not about trying to make me angry or be defiant. It was about something else going on inside of him. And it was just that reminder to me.

And, you know, I go in and read these books to a bunch of preschoolers. I’ve been going on the school tour. It’s the best book tour ever. I get to go to a bunch of preschools. And these four- and five-year-olds, they love talking about their emotions. You just get them started, and they really are so eager to talk to an adult. And so, I’d say if you’re sitting down to read a book like You Have Feelings All the Time, just pause, look at the pictures, and say, “What do you think she’s feeling right now?” There’s this spread at the end where they’re releasing butterflies at the end, the classes raised butterflies. And before I showed it to them, I think I said, “Well, how do you think everyone’s feeling because they’re about to release the butterflies?” “They’re excited, they’re happy.”

And then I show the picture. And there’s one man who’s scared, and there’s a baby who’s crying, and there’s a mom who looks stressed-out, and somebody’s flapping excited, and somebody’s sitting peacefully—because we have feelings all the time. And they’re not always what we expect to have. So, picture books are so, so amazing as their own genre, to be able to sit and read to kids and get them to think contextually and to just bond and just pause and point out, what are you noticing here? And often, they’ll notice stuff that we haven’t.

So sometimes, if you just pause and linger, you’re going to learn a lot about your kid just by hearing how they’re talking about the pictures. It’s magical. Get a library card, go stock up. To me, it’s one of the great benefits of parenting is that you get to read books.