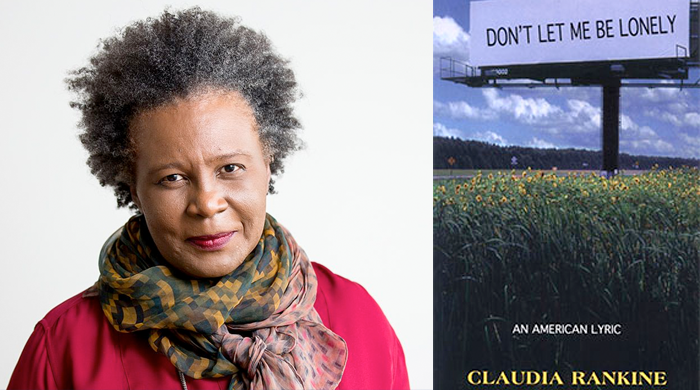

“Don’t Let Me Be Lonely” is an evocative exploration of loss. The book of poetry and prose vignettes opens with author Claudia Rankine as a child witnessing her father looking flooded, leaking, breaking, broken. He was grieving his own mother’s death, and Rankine climbed the stairs as far from him as she could, distancing herself from his unfamiliar expression.

“He looked to me like someone understanding his aloneness,” she writes.

The rest of the book ranges over the territory of loneliness–mourning, depression, oppression–with a poet’s flare for imagery and economy. A friend submitting to cancer, safekeeping her death with a do-not-resuscitate sign. Another gazing listlessly at the TV while asking for “the woman who deals in death,” meaning the show Murder, She Wrote. Her sister, a psychiatrist, unable to help herself after her husband and children are killed.

This is challenging terrain, but Rankine navigates it masterfully, evoking sadness, anger, and resignation without belaboring them.

She pierces our illusions with tight analyses of the news of the day, such as a 13-year-old convicted of first degree murder for killing a 6-year-old while play wrestling. “The boy was tried as an adult or he was tried as a dead child,” she writes. “To know and not to understand is perhaps one definition of being a child. Or responsibility is not connected to sense-making, the courts have decided.” This is an unexpected brand of poetry.

Her writing is particularly charged when exploring the visceral, personal experience of grief, disconnection and futility wrought by media depictions of racial violence. She juxtaposes the brutality of police sodomizing Abner Louima with a broken broomstick against the violence of a reporter asking him how it feels to be a rich man after he settles for $8.7 million.

The hybrid prose-lyric-poem form gives Rankine space to both describe and question her experience of news like Amadou Diallo’s senseless death in a hail of bullets. “Sometimes I think it is sentimental, or excessive, certainly not intellectual, or perhaps too naive, too self-wounded to value each life like that, to feel loss to the point of being bent over each time,” she writes.

The opposite, though, is the callousness of President G.W. Bush, unable to recall whether two or three people were convicted for dragging a black man to his death in Texas.

I forget things too. It makes me sad. Or it makes me the saddest. The sadness is not really about George W. or our American optimism; the sadness lives in the recognition that a life can not matter. Or, as there are billions of lives, my sadness is alive alongside the recognition that billions of lives never mattered. I write this without breaking my heart, without bursting into anything. Perhaps this is the real source of my sadness.

The poetry of “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely” is most of all, I suppose, in Rankine’s refusal to argue a point or come to a clear conclusion. In her decided opacity on what to do with the tensions she’s illuminated, revealed in the abundant white space separating passages. And, of course, in the occasional verse.

Define loneliness? Yes. It’s what we can’t do for each other. What do we mean to each other? What does a life mean? Why are we here if not for each other?

Quoting Paul Celan, she concludes the book by likening a poem to a handshake. “The handshake is our decided ritual of both asserting (I am here) and handing over (here) a self to another,” she writes. “Hence the poem is that–Here. I am here.”

It feels like this is her way of saying, my work here is done. I’ve extended my poem, myself. Don’t let me be lonely. Perhaps that’s all we ever get — an extended hand, a call to risk connection.

If this review resonates with you, I bet you’ll enjoy my newsletter. I regularly send bookish news and notes out to more than 1,000 readers. Sign up here.