A defining moment in Elizabeth Warren’s life was watching her 50-year-old mother wrestle herself into a worn black dress typically reserved for funerals and head out for her first job interview. The family was in dire financial straits after Warren’s father suffered a debilitating heart attack and her mom wasn’t going to lose their house without a fight.

“The dress was too tight—way too tight,” Warren writes in “A Fighting Chance.” “It pulled and puckered. I thought it might explode if she moved. But I knew there wasn’t another nice dress in the closet. And that was the moment I crossed the threshold. I wasn’t a little girl anymore. I stood there, as tall as she was. I looked her right in the eye and said: ‘You look great. Really.’”

Her mother got the job answering calls at Sears, and Warren got an education in walking straight ahead, no matter how tough the going (or wobbly the heels).

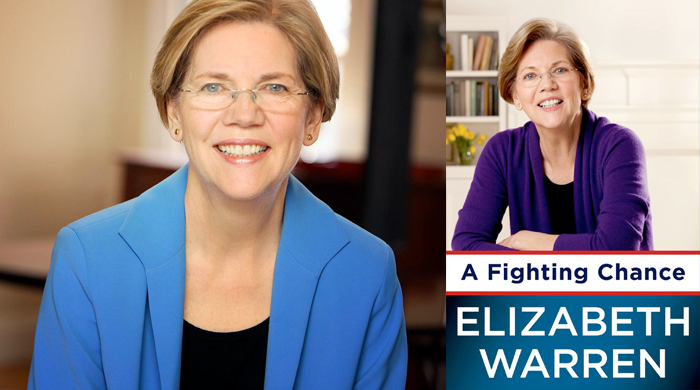

Personal stories like this make Massachusetts Senator Warren a compelling character in her political narrative. Ultimately, though, the family dramas she recounts are mere asides. The memoir’s primary concern is combatting the big corporations, lobbyists and billion-dollar tax loopholes that she believes rig the game against working families.

“It’s not meant to be a definitive account of any historical event—it’s just what I saw and what I lived,” she writes of her book. “It’s also a story about losing, learning, and getting stronger along the way. It’s a story about what’s worth fighting for, and how sometimes, even when we fight against very powerful opponents, we can win.”

I would expect nothing less from the former Harvard Law professor and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau visionary. But more than her policy prescriptions and political rhetoric, the book struck me with her enviable courage, consistency and fight. Here are a few unexpected takeaways from the senior Senator from Massachusetts.

Bloom where you’re planted. Career “experts” encouraged my generation to seek “dream jobs” at the intersection of our unique talents, passions and skills. Problem is: Most of us need real jobs, the kind where pay stubs meet living expenses, and those are often less than dreamy.

Warren’s expectations were much lower as a young professional. For her, working — period — was a triumph, because married women were expected to stay home with kids. She got one job offer after law school, and part-time at that, but she accepted and relished it, striving to make it meaningful. She taught legal writing with gusto, and when her husband’s job transferred, she cold-called a law school to win her next gig—a real professorship. In short, she sought “better,” not “perfect,” and kept taking the next step.

The long arc of Warren’s career is instructive. When she had small children, her teaching, writing and research hours were limited, but she never abandoned them altogether. By putting one foot in front of the other day after day, cranky toddlers and all, she laid a strong foundation of expertise—and indignation—that propelled her all the way to the Senate, where she arrived at 62.

Outrage can drive a career. Notably, her rise from legal writing instructor to bankruptcy law expert to the U.S. Senate wasn’t fueled by a love of the law. Rather, a deep disdain for the injustice of some laws and a commitment to fighting for change spurred her on. This notion that pain points, not warm fuzzies, are worthy motivators is powerful.

Warren’s book is filled with her visceral reactions to injustice. When a world-famous law professor couldn’t support his negative claims about people in bankruptcy with data, her teeth hurt. National Bankruptcy Review Commission hearings made her gag. Politics felt dirty, and the cynicism of banks who preyed on vulnerable families infuriated—and motivated–her.

In each instance, she adopted a fighter’s stance and hustled to learn enough about the problems to propose and advocate for effective solutions. She took it all very personally. “My daddy and I were both afraid of being poor, really poor,” she writes. “His response was never to talk about money or what might happen if it ran out—never ever ever. My response was to study contracts, finance, and, most of all, economic failure, to learn everything I could. My daddy stayed away from big sores that hurt. I poked at them.”

Never be afraid to pick a fight. Throughout the book, Warren uses the language of direct confrontation to describe her work. She chooses battles, wrangles with opponents, and punches back—all to give working people a fighting chance. Whether snatching a microphone from a bankruptcy judge on a panel or railing against industry-backed bills, her message is consistently loud and clear.

Amid the pitched battle for a consumer protection agency, she refused to see it gutted. “My first choice is a strong consumer agency,” she said. “My second choice is no agency at all and plenty of blood and teeth left on the floor….My 99th choice is some mouthful of mush that doesn’t get the job done.”

Love her or hate her, you always know where she stands. May we each learn to fight our own good fights with such urgency and resolve.