I know my opinions make an impression—among people inclined to agree with me, anyway. My confidence in influencing those with divergent views, however, is so low that I generally avoid addressing controversial issues with them at all. I wouldn’t talk guns or race with a Republican, for example. I’ve read one too many reports on partisan polarization to go there. To be fair, I’ve offered similar silence to some on my side of the aisle, too, especially the “colorblind” and others who may be well-intentioned but willfully ignorant. My pragmatism, I’ve long told myself, won’t allow wasting breath in futile debate.

But for the new year I’m open to engaging in the kind of fraught conversation I’ve typically shunned. I turn 40 this year and feel like it’s time to drive change instead of staying cloistered in a comfortable place. Dramatic shifts in public opinion on same-sex marriage, gender-neutral pronouns, and more give me hope that minds can be changed about the value of racial equality, immigration, and climate action, too. This year, I aim to learn the tools of persuasion that work and use them to do my part to fuel equity and social progress.

Though I’m still likely to avoid the aggravation of live debate, I’ve resolved to share my views more widely via regular opinion pieces and essays. Putting arguments out there, listening to the responses, and genuinely seeking common ground to pursue is perhaps the best any of us can do. What looks like sweeping change is usually hard won step by step.

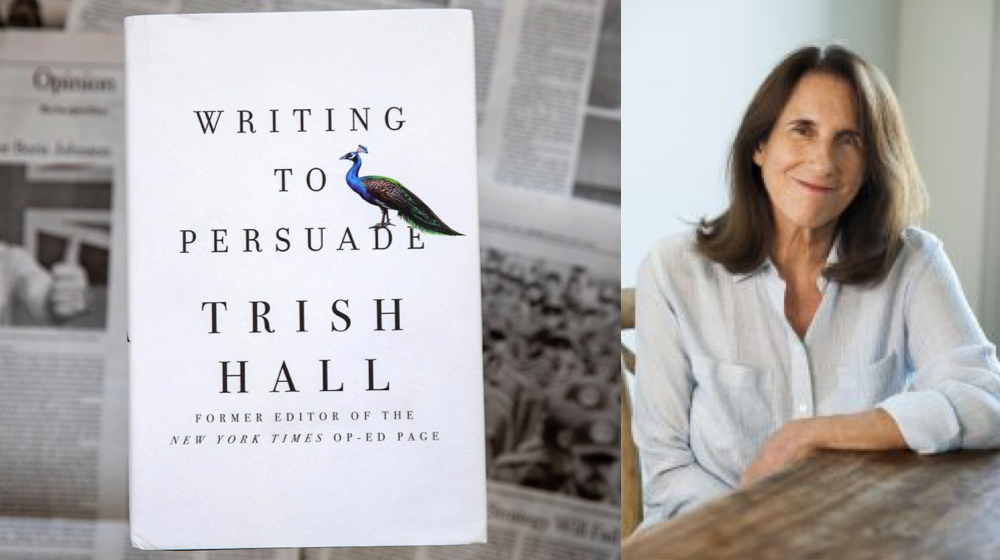

To gear up to this challenge, I read Writing to Persuade by Trish Hall, a former editor of The New York Times Op-Ed Page. The book promises “techniques for bringing people over to your side not only in written arguments, but in life.” Here are a few takeaways from her distillation of scientific research on persuasion and her years of opinion editing.

Argue from the perspective and values of those you seek to persuade, not your own. “Despite our culture of selfies, persuasion is not about you; it’s about them,” Hall writes. That means you have to listen to, and understand your audience in order to influence them. Facts alone, however eloquently presented, do not move people to embrace new views. Any arguments made without listening first are likely to be dismissed or ignored. One classic op-ed approach is to start by establishing common concerns or shared values and then to bridge into areas of contradiction or disagreement. Building rapport aids readers’ receptiveness to challenging ideas. “You’re more likely to get the argument moving if you’ve agreed on some baseline issues and only then try to move it in another direction,” she writes.

Write clearly, directly, and vividly. Terrible writing of all kinds flooded Hall’s inbox during her time leading the Opinion section at The New York Times. “Manicured products of Ivy League schools offered tangled sentences and mundane musings,” she wrote. “People whose novel ideas deserved a hearing could not escape their jargon long enough to reach an audience.” To avoid these pitfalls, she advises a straightforward approach—making just one to two points and presenting them logically and intelligibly. The book offers before and after examples to illustrate the depth of pruning that’s sometimes required to achieve this.

Speak from experience. To persuade, you must bring authority. It helps to write on topics where you have deep involvement or understanding. Then you can use your singular perspective, sensibility, and knowledge to present the stories, concrete details, and vivid imagery needed to make your best case. “No matter how you get there, you have to write from your deep self,” Hall urges. “If you stay at the level of your office brain or your academic self and use the jargon of your profession, you will kill your work. You might not even know what story you want to tell until you think about what you, and only you, can offer.” Often revealing intimate, personal details makes the writers more human and the pieces more memorable and powerful.

I’ve presented a few highlights of Hall’s book, but recommend reading Writing to Persuade for the full complement of this top editor’s stories and insights. Her matter-of-fact style and rich examples cut to the heart of key topics for budding essayists: where to find great ideas and how to pursue, pitch, and develop them to persuasive effect.

She also offers helpful reminders of why we should venture opinions at all. “Engaging with the world, whether through writing or in person, is what the world is, what life is,” she writes. “We are all in this together, and our words connect us in the most primal and profound way.”

How open are you to discussing controversial issues with people who may strongly disagree with you? Why is it important to pursue common ground? Has an op-ed or personal debate ever led you to change your mind on an important matter?