Set in 1987, it maps Angie Mackenzie’s fraught journey to retrace her deceased sister Ella’s steps from Detroit to Lagos, and bring a sense of closure to her mourning. Since Ella’s death, Angie had been stuck–unable to forge her own identity. She’s lived instead “as a kind of caretaker to the obsessions Ella left behind, an executor of her sister’s Afrocentric politics, new age beliefs, Fela Kuti devotion.”

But by 1987, four years after Ella’s death, times had changed. The African Liberation Day celebration in Detroit had shriveled, Fela was strung out, and Angie sporting her dead sister’s caftan and haunting her grave was long-past worrisome. She set off for Lagos Island, Ikeja and Surulera on a “hajj of some sort, yearn[ing] to return more certain of who she was, of what she could do in the world. Figure out what type of black person to be.”

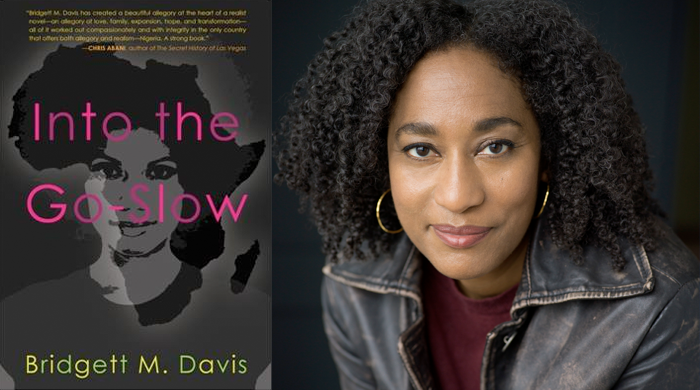

Author Bridgett Davis makes a risky choice in telling this story through Angie, a thin, grasping imitation of Ella. It mutes the book’s most lively character and reduces Ella’s charisma and many compelling experiences to plot points along Angie’s quest for resolution. The effect is to dampen the urgency of some of the book’s best material. Pivotal moments in Ella’s life become, in Angie’s mind, mere explanations for her ultimate demise, making the tale a bit too pat and tidy.

Davis references a great deal of African-American history–the family’s migration north, Jim Crow, “black firsts” (the first black woman jockey, the first black woman congresswoman…), the Black Power movement. It provides important context for Angie’s journey and a counterpoint to what she learns of African current events, illuminating the dramatic personal, social and cultural change sweeping through countries on two continents.

Occasionally, though, the historical references to coups and crack, apartheid and AIDS feel forced into a story that’s principally about grieving, not racial consciousness. That Ella was “deep into the struggle, a dedicated Pan-Africanist” feels less important than that she was dynamic, loved, and greatly missed.

Stalking Ella’s memory proves to be extremely dangerous for a single woman in Nigeria, and naive Angie belatedly realizes that Ella didn’t make her journeys to Africa alone. Big sis was always a part of a delegation or with her on-again-off-again boyfriend Nigel. Davis hits her stride in the latter part of the book when she vividly describes Nigeria in all its poverty and prosperity, with many shades of lifestyle, identity, and culture in between. It’s a much more textured depiction than the one offered of Detroit, which is principally set in stores or in front of television sets.

Like the “go-slow” in Lagos for which the book is named–its notorious traffic–the novel’s direction is clear from the outset, but so dense with characters and activity that you don’t know when you’ll arrive. Be forewarned. It’s quite a ride and the destination may not warrant the travel.

If this post resonates with you, I bet you’ll enjoy my newsletter. I regularly send bookish news and notes out to more than 1,000 readers. Sign up here.