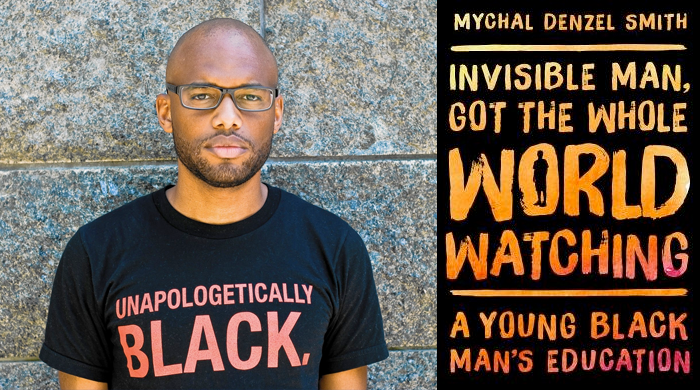

Necessary and audacious, Mychal Denzel Smith’s assured debut, Invisible Man, Got the Whole World Watching, fuses memoir and cultural criticism to ponder an often-neglected question: How did you learn to be a black man?

The way he scrutinizes the origin of his beliefs about black identity and masculinity is revelatory–and instructive. He mines his personal history as an Obama-era black millennial in the service of a larger vision: social transformation through personal awakening.

As he traces his own education, through family, books, music, comedians and college, he illuminates a way forward for anyone willing to grapple with their own cultural inheritance. He models a process for questioning convention and envisioning a new self and a new world freed from past constraints.

He credits truth-tellers including Malcolm X, Mos Def and Aaron McGruder with raising his black radical awareness. But, just as importantly, interrogating those influences spurred his black liberation imaginings. When you critique your culture, appraise your morals and shatter your worldview, you have a shot at growing up whole, he posits. You have a chance to create something other than the self-hatred, violence and mental illness all around us.

The journey can feel isolating. He learned that most people, even fellow students at the historically black college he attended, don’t share his enthusiasm for fighting black oppression head on. “I expected to engage thousands of other young black budding intellectuals about the politics of racism, and how we might unite and organize to bring down the system, with our struggle-weary professors guiding and cheering us along,” he writes. “Instead I found thousands of mini-Obamas and an administration happy to indulge in their delusions.”

Yet he also found books and people on campus who nudged him forward. A professor suggested that he move beyond the “SAY IT LOUD, I’M BLACK AND I’M PROUD” literature to consider how gender affects power and politics in ways black men often don’t consider. Thus, “And what of ‘the black woman’?” gets added to Smith’s question list and Angela Davis, Assata Shakur, Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez and Toni Morrison eventually join his intellectual universe.

Of this transformed perspective he writes:

These black men were my guides through the minefield of identity when faced with racism. I was attracted to the bravado, to the reclamation of black excellence. I wanted to absorb their performance of black arrogance as a corrective to self-loathing. But what I hadn’t considered was how that ego was gendered. I spent my childhood passively absorbing white supremacist ideas of my invisibility, then unconsciously shrinking myself from the world. Everything I read, listened to, and learned validated my right to existence as a black man in America. But that wasn’t the whole equation. Everything I read, listened to, and learned validated my right to existence as a black man in America, but only within the confines of a patriarchal definition of masculine identity. What went unquestioned were the ways my newfound sense of black manhood contributed to the ongoing marginalization of my mother, her twin sister, my grandmother, my high school guidance counselor, and more than half the student population on Hampton University’s campus. I began to see myself, but only by refusing to see black women.

Smith’s emphasis on questions over answers may frustrate readers seeking a specific cure-all for The Race Problem. But his depth and candor in exploring the making and remaking of his own identity illustrate an important first step: To fight a system of oppression you must understand how pervasive it is and how you are complicit in it.

This review is an excerpt from an interview that can be read in full here.

If this review resonates with you, I bet you’ll enjoy my newsletter. I regularly send bookish news and notes out to more than 1,000 readers. Sign up here.