Book page flowers make such pretty decor. We have done a few different DIY book page flowers in this craft series. Why not make them all and combine them into a beautiful arrangement?

I have to say, I was staying away from roses because of how intricate and delicate they look. I thought making a DIY paper rose was going to be so much harder than it turned out to be. So don’t shy away from this beautiful flower! If anything, it’s actually simpler than some of the other flowers we’ve created.

Modify this craft for kids by using glue dots instead of a glue gun and letting them color or decorate the flowers. Let their creativity soar—not all roses are red!

Materials Needed:

- Old book pages

- Ruler

- Scissors

- A toothpick

- Glue gun (or glue dots for a safe alternative)

- Chopstick, pipecleaner, popsicle stick, twig, wire, or anything you can use for a stem

- Optional: Decorating materials (stickers, colored pencils, glitter, etc.)

Cost: This craft uses pretty basic supplies, most of which you may have around the house. I decided to use a chopstick for my stem, but you can get creative with a different material for that if you don’t have an old takeout chopstick in your junk drawer. I listed a few alternatives above!

Step 1: You will need to cut 3 squares of equal size from the pages of an old book. Note: each rose needs 3 squares, so if you are making more than one rose, you’ll need to cut out more squares. I used 5 inch by 5 inch squares. You can go bigger than this, depending on the size of your old book pages, but I wouldn’t recommend going much smaller than 5 inches or it will be difficult to fold and glue the petals together!

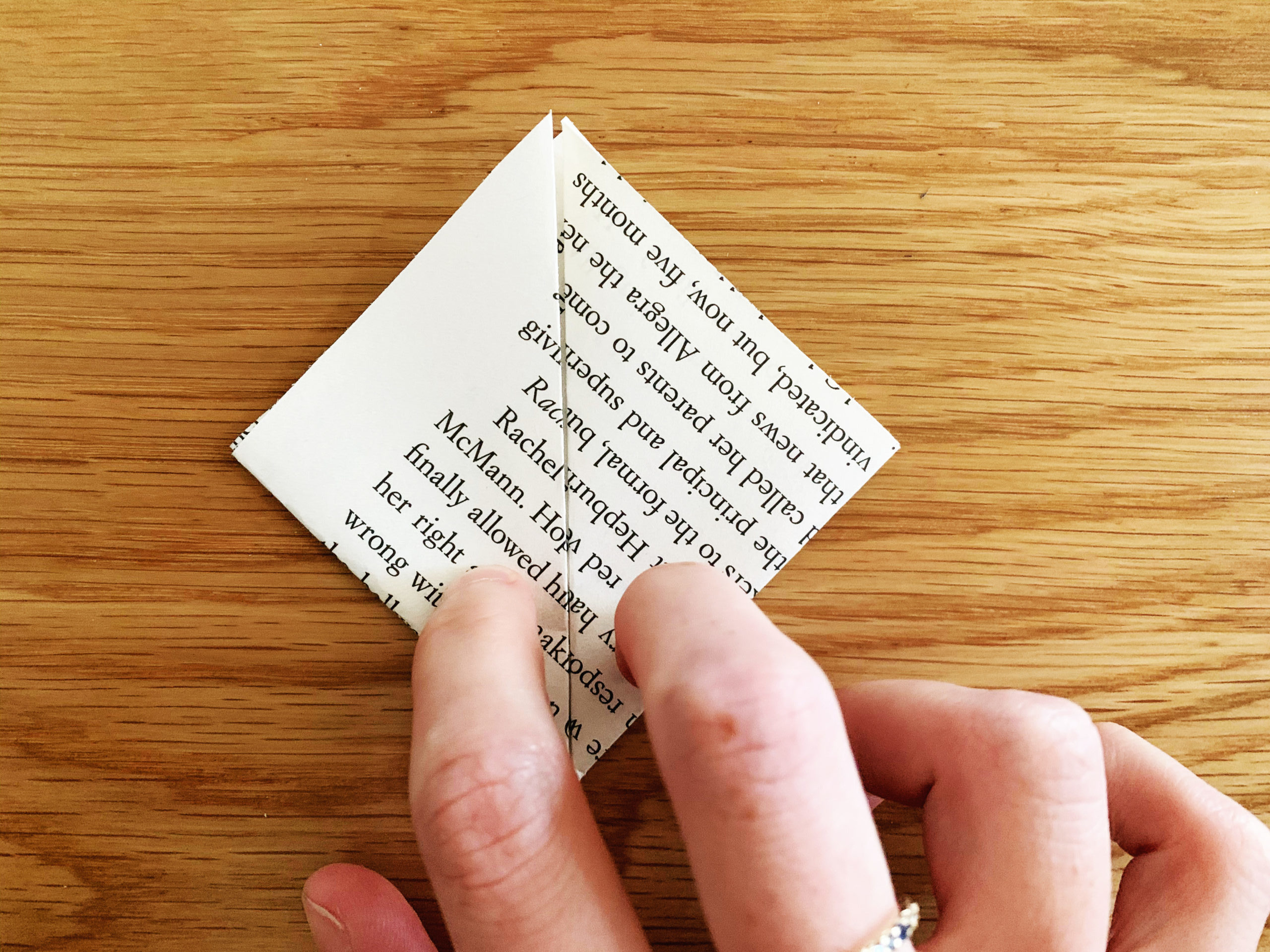

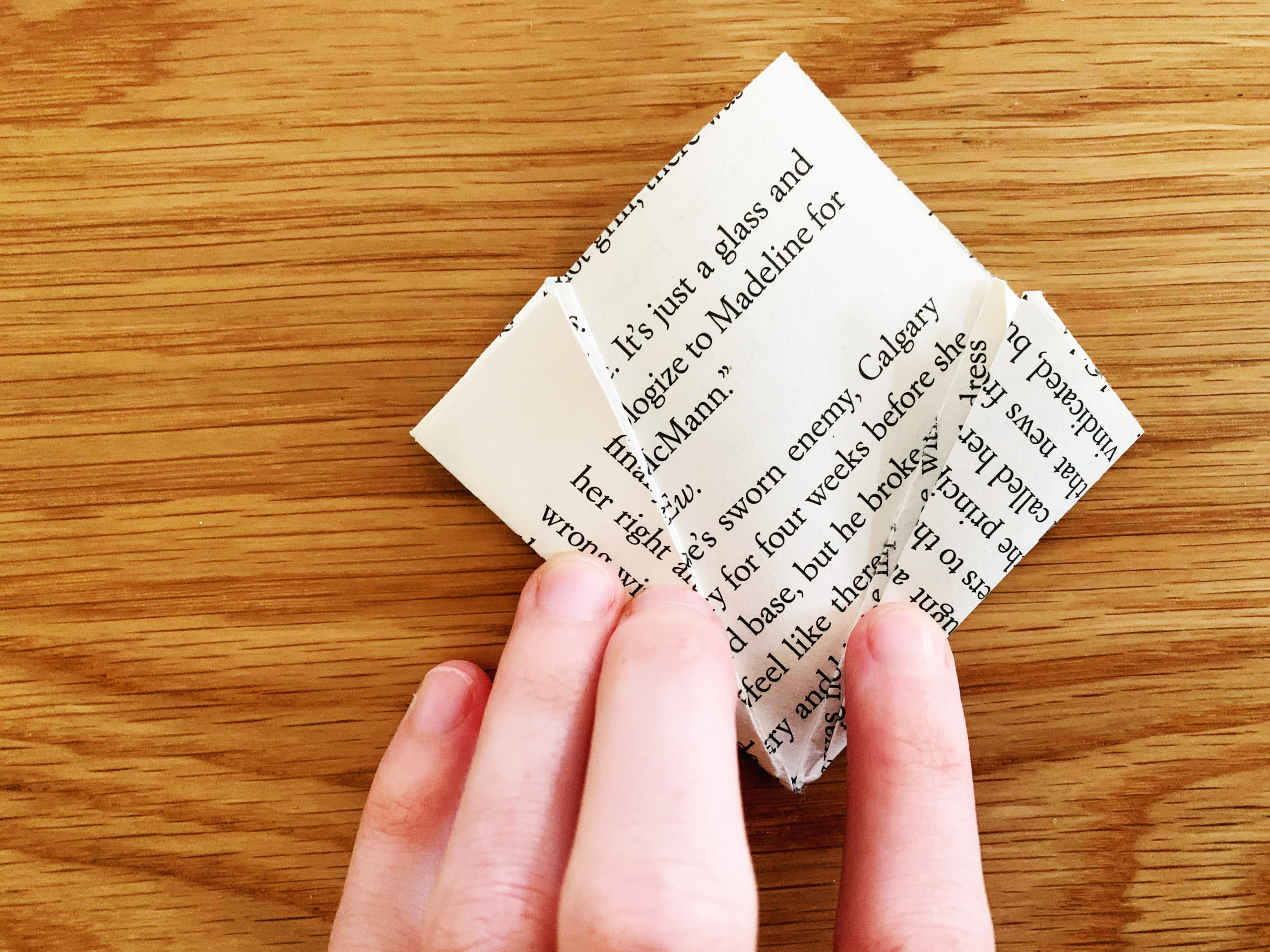

Step 2: Next, fold each of your 3 squares into a triangle, then fold that into a smaller triangle and finally fold that into a still-smaller triangle. The end result should be 1/3 the size of the first triangle.

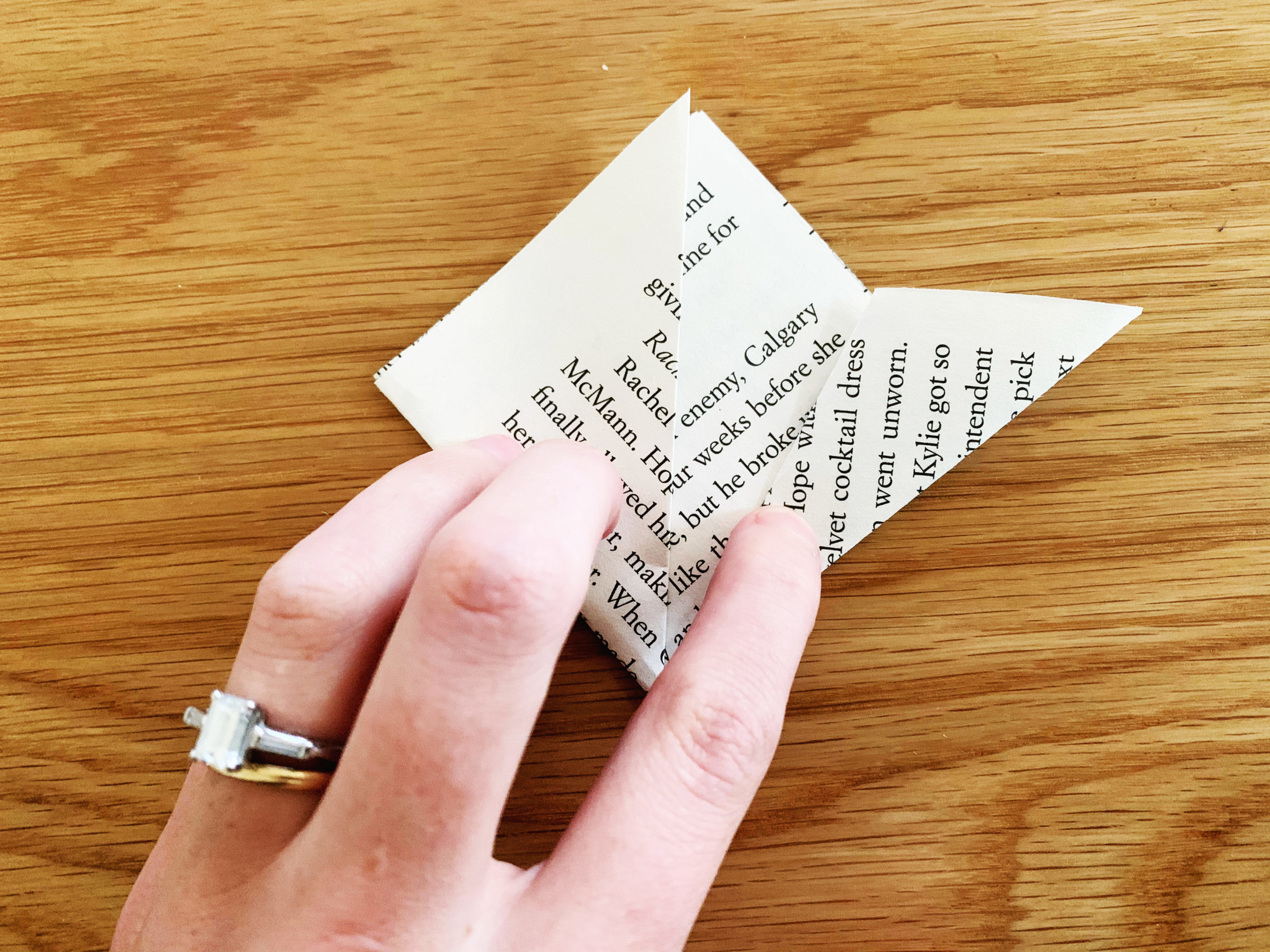

Step 3: Take one of the small triangles and keep it folded, with the pointed end facing down. Now you will cut the open top to make a dome shape (it should look like an ice cream cone). Repeat this cut with the other 2 folded triangles. Pro tip: Make sure the folded edge is facing the same way each time!

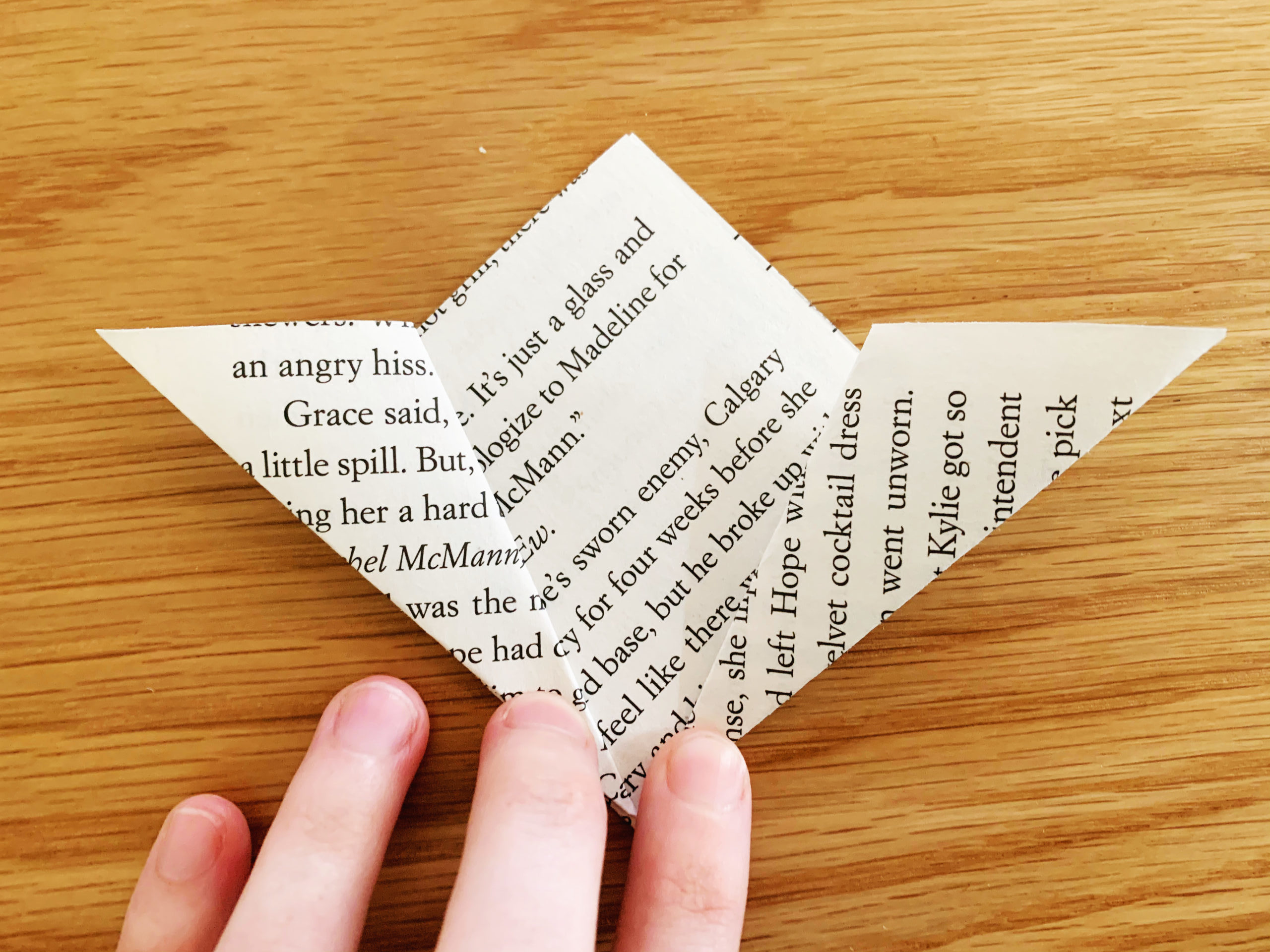

Step 4: Holding all 3 in your hand, cut off the bottom point of the triangle, leaving a small hole at the base of each triangle.

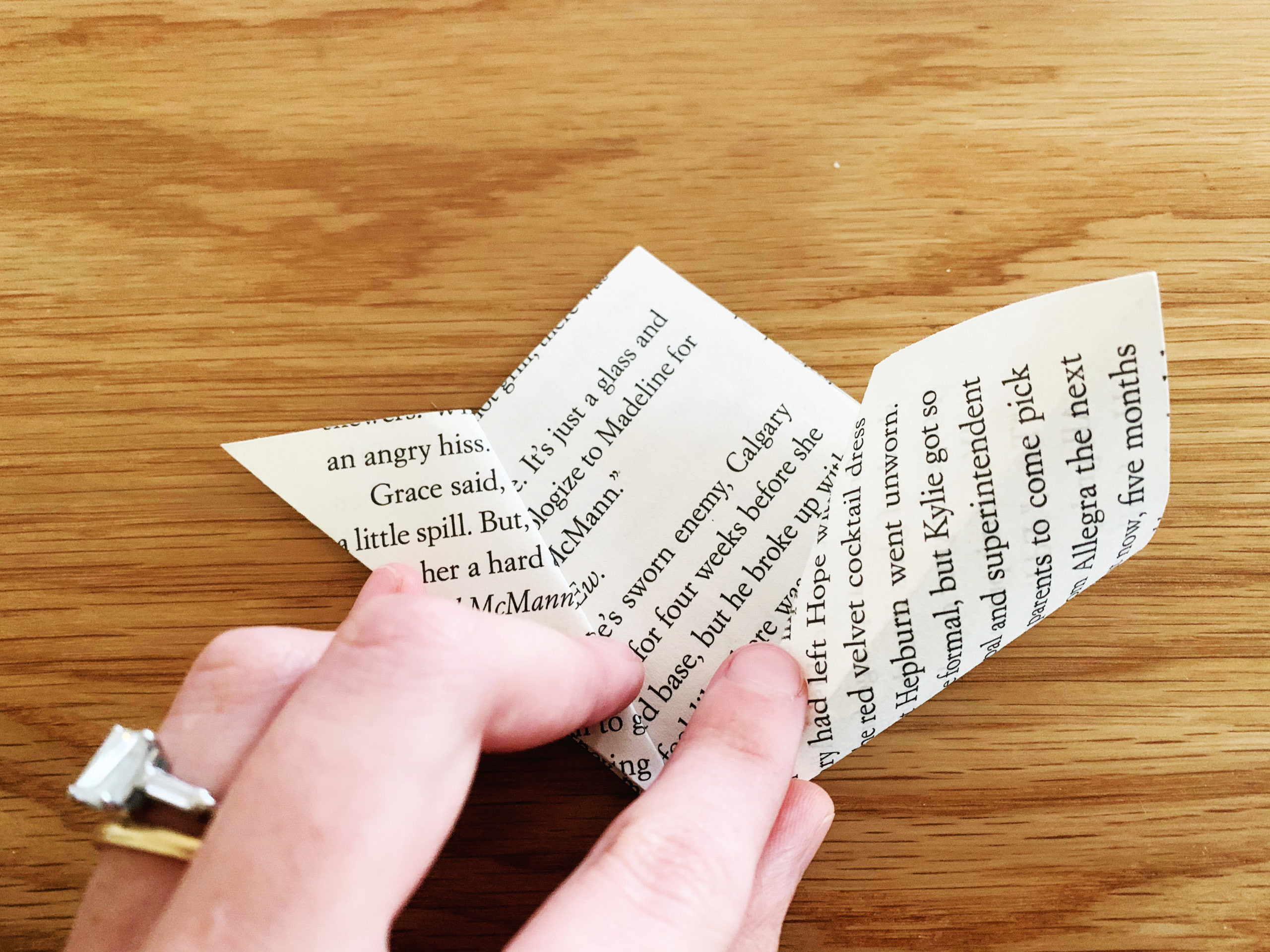

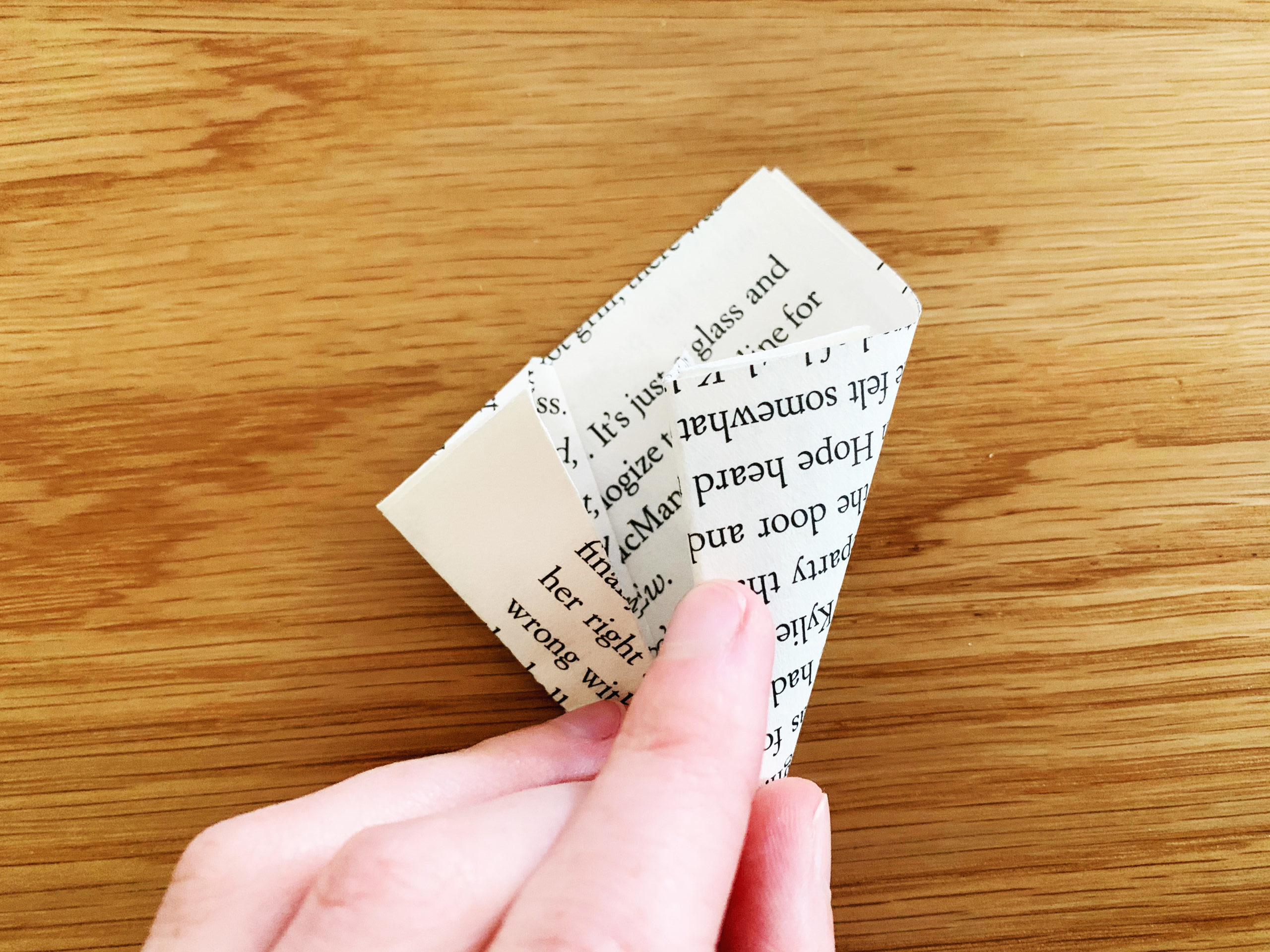

Step 5: This next step might seem complicated, but it’s not! Just go slow and count your petals. To start, unfold all your triangles. They will all start with 8 petals. From the first flower, cut out 1 petal. From the second, cut out 2 petals. And from the third, cut out 3 petals. You will now have 6 flower pieces: one with 1 petal, one with 2 petals, one with 3 petals, one with 5 petals, one with 6 petals and one with 7 petals.

Step 6: Using a hot glue gun or glue dots, stick the edges together on the 3-, 5-, 6- and 7-petal pieces, as shown below. Just overlap the edges a bit when you glue them together.

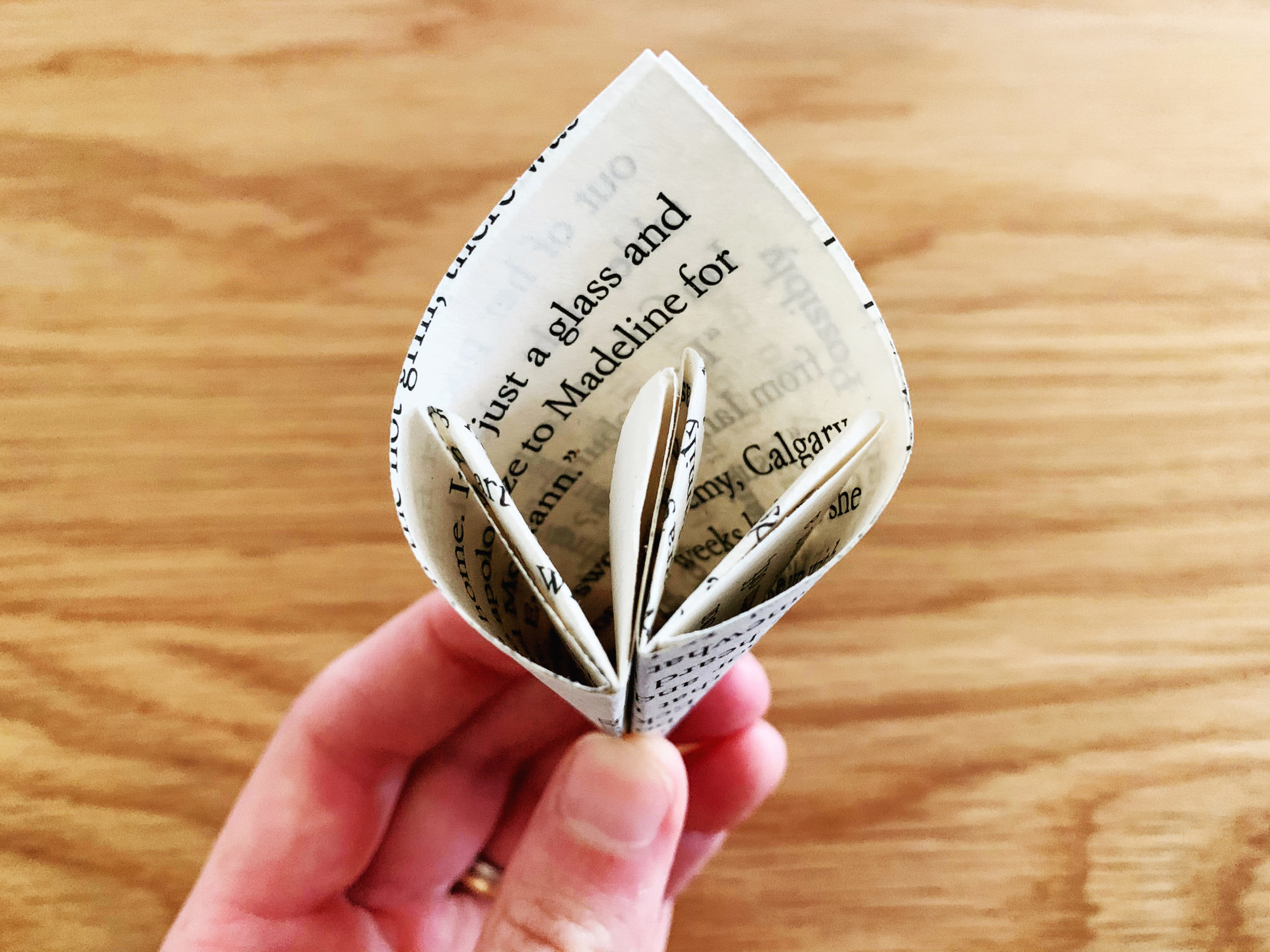

Step 7: Once the glue has dried, take your tooth pick and carefully roll the very top edge of the petals outwards. Then take the two last flower pieces that you haven’t touched yet, the single petal and the 2-petal piece, and completely roll these two pieces around the toothpick.

Step 8: Now it’s time to assemble your flower. Starting with the largest piece (7 petals) add a little bit of glue on the inside of the base and place the next smaller piece (6 petals) on top. Then glue the 5 petal piece to that and so on. Eventually the base of the 3-, 2- and 1-petal pieces will poke through the hole in the middle of the flower.

Step 9: You’re almost there! Last but not least is to add your stem. Put a decent bit of glue on the end of your chosen stem. Starting with the unglued side, stick that down through the center of your finished flower and pull it through so the glued end sits inside the flower.

Once the glue is set, your beautiful book page rose is complete! Are there other DIY paper flowers you’d like to learn how to make? Let us know what your favorite florals are and we can add them to our list of DIY book crafts to share!

With just a little help, kids can craft these handmade book page pinwheels. This is a fun activity in its own right, plus they’ll get a new toy to boot! You can make them to keep or to gift—this is a great present for older children to make for younger siblings or friends.

Like many of our DIY book crafts, you can really make this project your own. Keep your pinwheel simple or have some fun coloring and decorating it! Younger kids may enjoy adding stickers and glitter (don’t they always?) and you can also play around with using different pencils. There are some really cute ones out there, including options for various holidays and themes! Fun idea: Shade each wing with a single color for a classic color-block look.

Materials Needed:

- Old book pages

- Wooden pencils with erasers

- Scissors

- Straight pearl sewing pins

- Needle-nose pliers

Optional:

- Colored pencils, markers, or even water colors

- Other items for decorating: stickers, glitter, feathers, or anything you have on hand

- Glue

Cost: If you have these basic supplies already on hand, this craft could cost you nothing! Needle-nose pliers are small and easy to use, but really any pliers will work to bend the sewing pin a bit, so don’t worry if you don’t have specifically needle-nose pliers. A pack of pencils should run you a few dollars, if you’re fresh out of ones with the erasers intact. And if you need to buy some straight pins, packets should start at around $4.

Step 1: Using pliers, bend pins to create a 90-degree angle, approximately 1/3 of the length up from the pin’s pointed end.

Step 2: Cut out a 4″x4″ square from a book page (you will just need one square per pinwheel).

Step 3: Make four diagonal cuts from the corners toward the paper’s center, stopping at least half an inch shy of the center. If you want to color or decorate your pinwheel, now’s the time. (Any rigid stickers will need to be added after the last step, though.) Be sure to let any paint or glue dry before the next step.

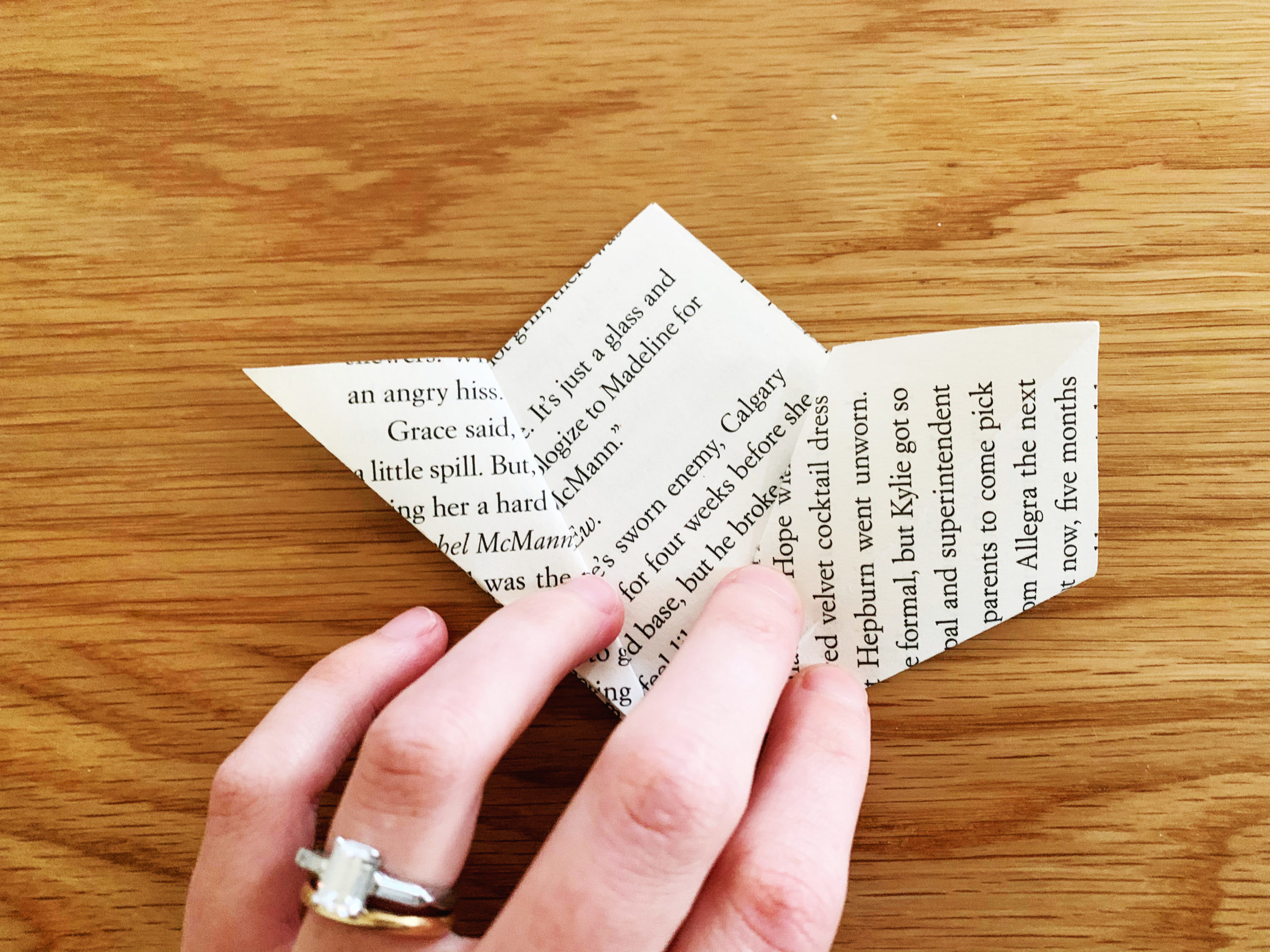

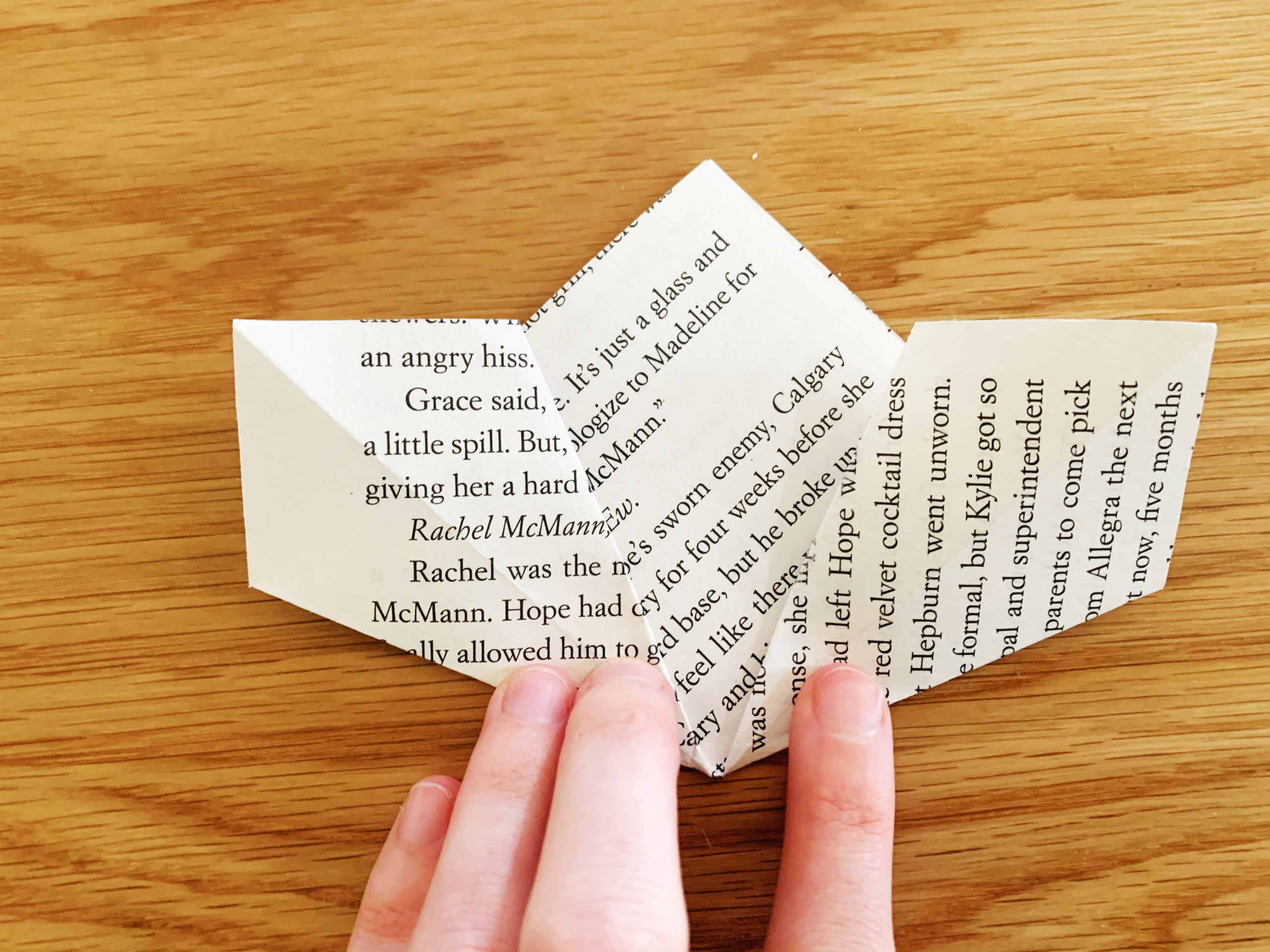

Step 4: Now, to assemble the pinwheel, fold the left point of each triangle lightly toward the center (no creasing).

Step 5: Hold the four folded points in place while you push a pin through the center (from the front of the pinwheel towards the back), being careful to make sure that you catch all four folded corners. If you’re working with kids, you’ll probably want to do this step for them.

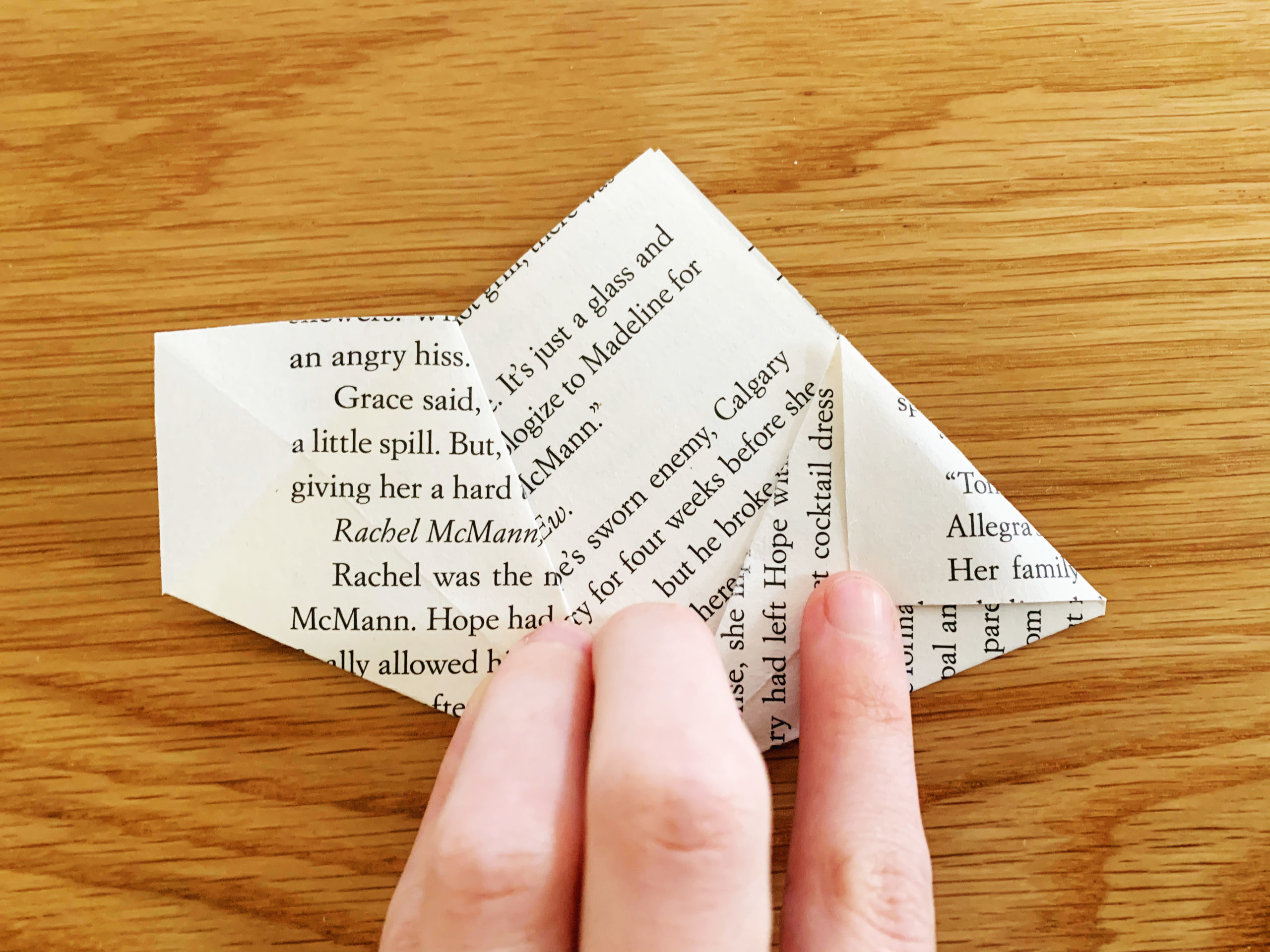

Step 6: Next, gently guide the paper around the bend in the pin, sliding the pinwheel out to the pin’s pearl end.

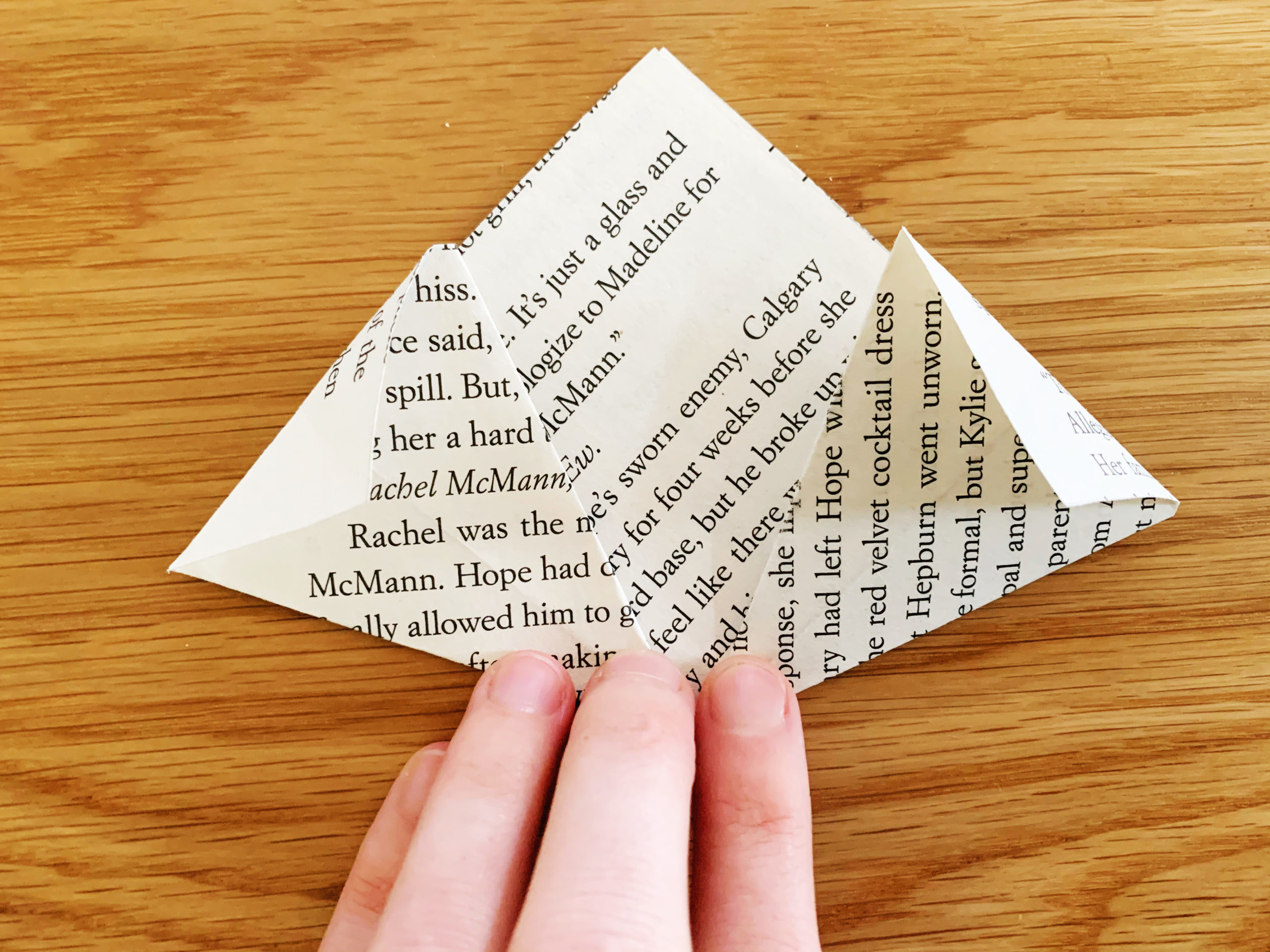

Step 7: Finally, firmly press the pin’s pointed end straight down into the pencil’s eraser.

Hooray! Your pinwheel is complete—give it a spin! You can make a few of these and place them in a mason jar for a cute new table decoration, or add them to an outdoor flower pot, like I did. Kids could even make a bunch for a pinwheel parade. Have fun!

Looking for a creative way to decorate (or something to do with that falling-apart paperback)? From back-to-school to book club to birthday celebrations, you can customize this adorable DIY book page banner for any holiday or theme. It’s easy to make, yet creates a cute and polished end product.

Kids can dive right into this DIY book craft. Have them spell out their name on the banner and hang it above their bookshelf or bed. Or let them make one to celebrate a relative, friend, or favorite teacher. Whatever message you choose, this cute craft is done in no time, so it’s easy to make several for a special event or to give your daily spaces … say, that home learning “classroom” … a fun facelift.

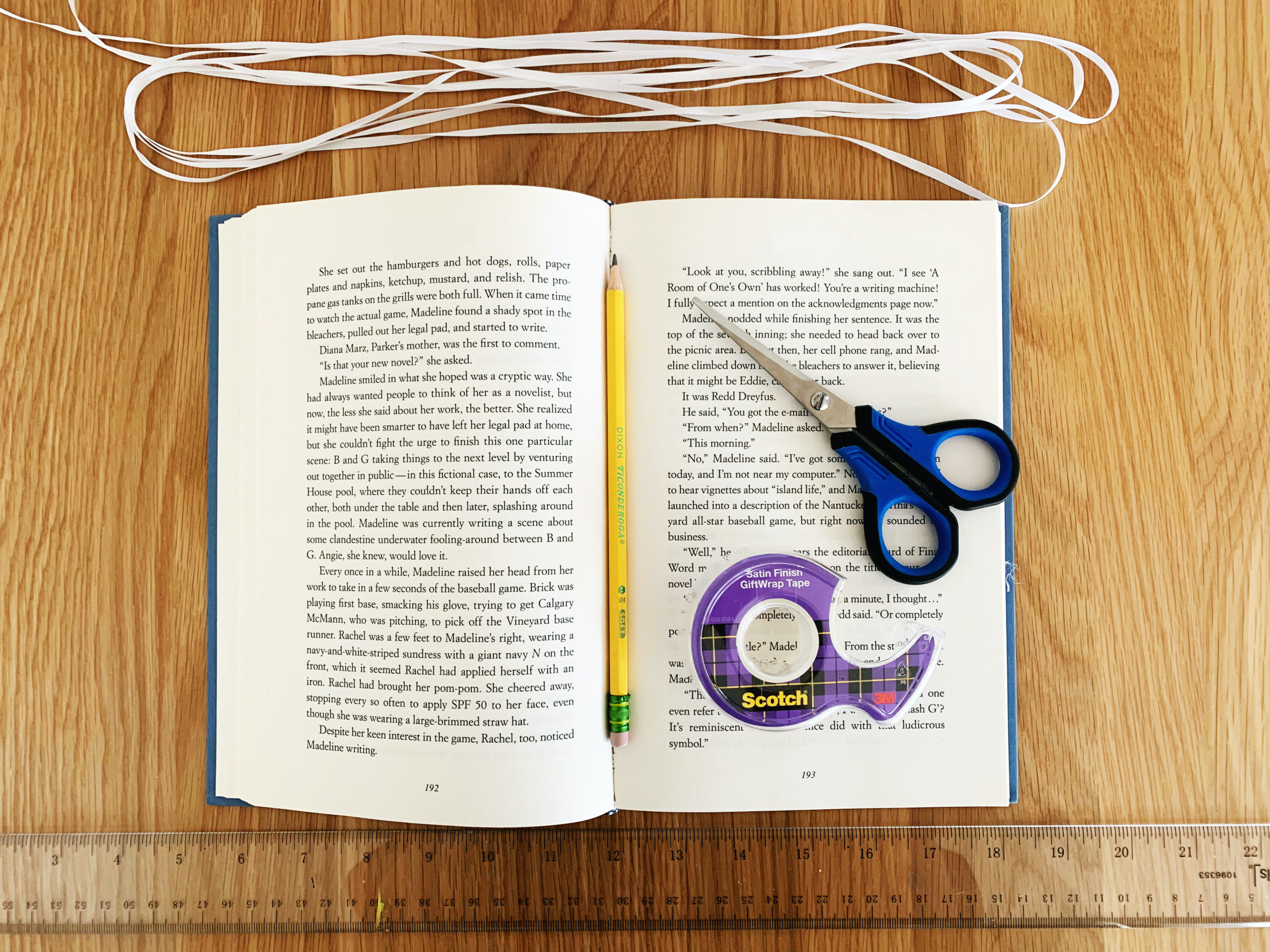

Materials:

- Old book pages

- Scrap paper (to make a template)

- Scissors

- Tape

- Pencil

- Colored pencils or markers

- Twine, yarn or ribbon

Cost: This craft should not cost you anything, provided you’ve got a few basic supplies on hand.

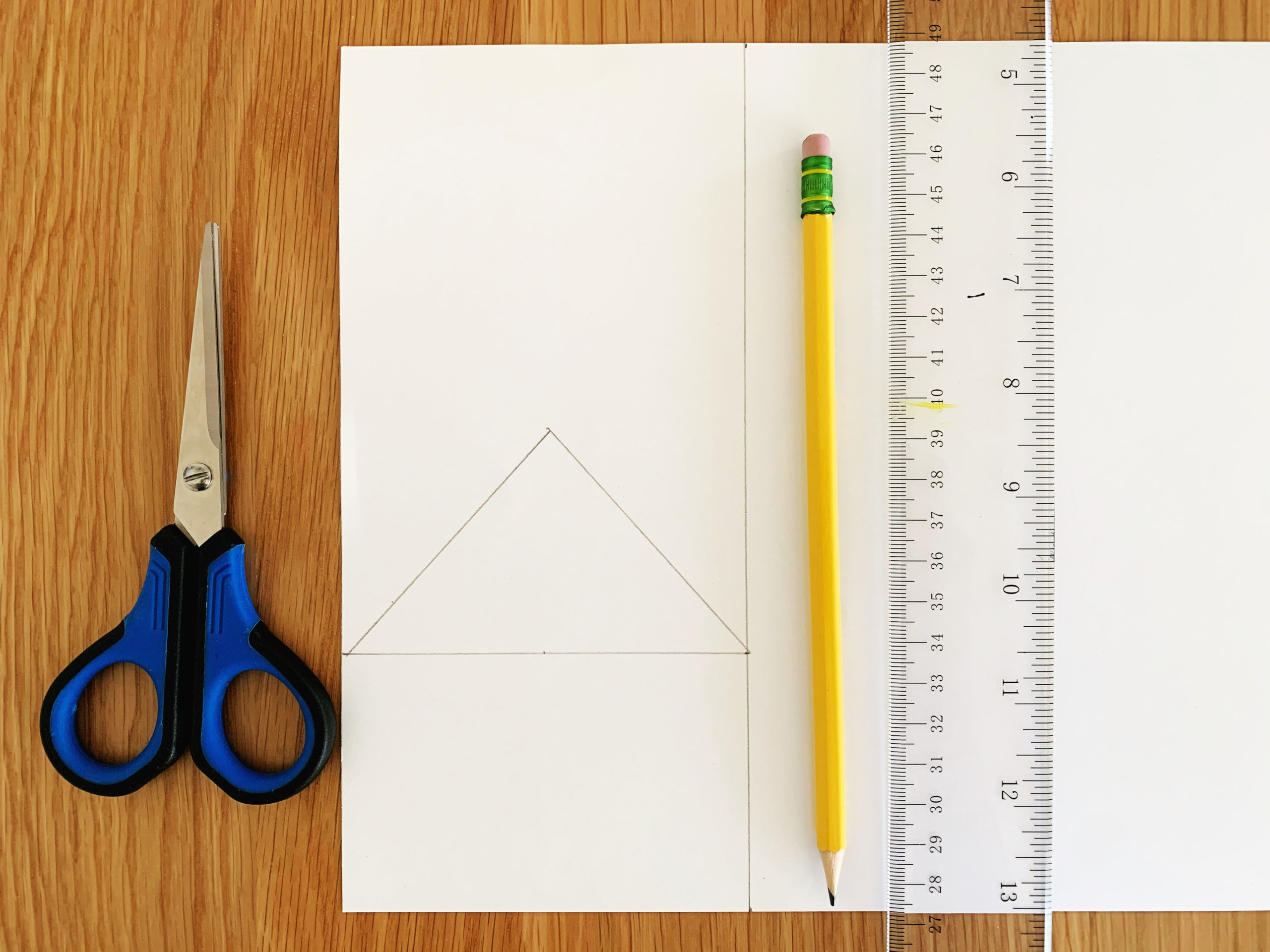

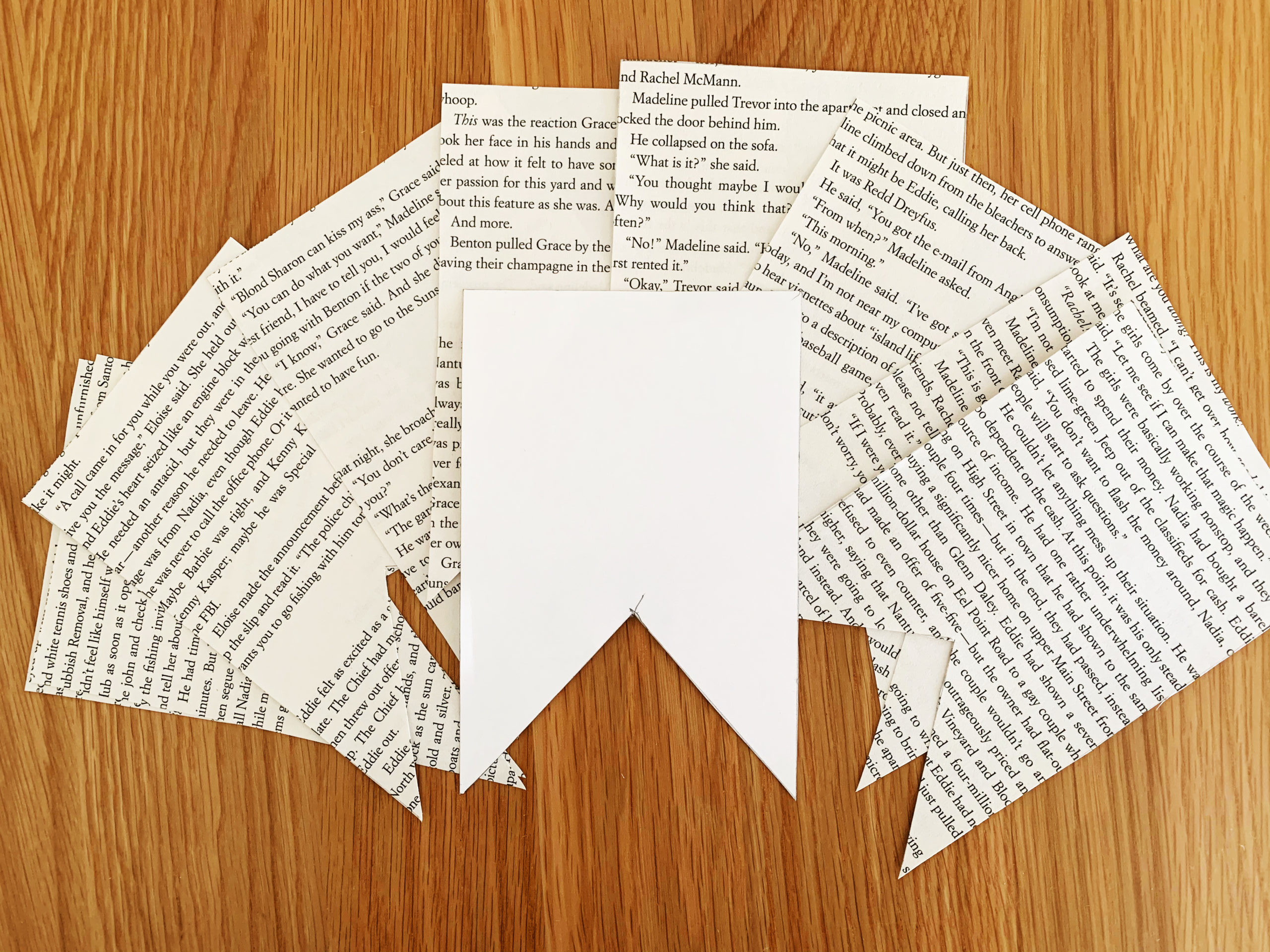

Step One: Step one is to make the template you will use to cut out your banner pieces from the book pages. Just draw the shape you want on some scrap paper, preferably stiffer paper or cardstock if you have it. I decided to do a cute flag shape for my banner, so I cut a 4 x 6-inch rectangle and then cut a notch in the bottom

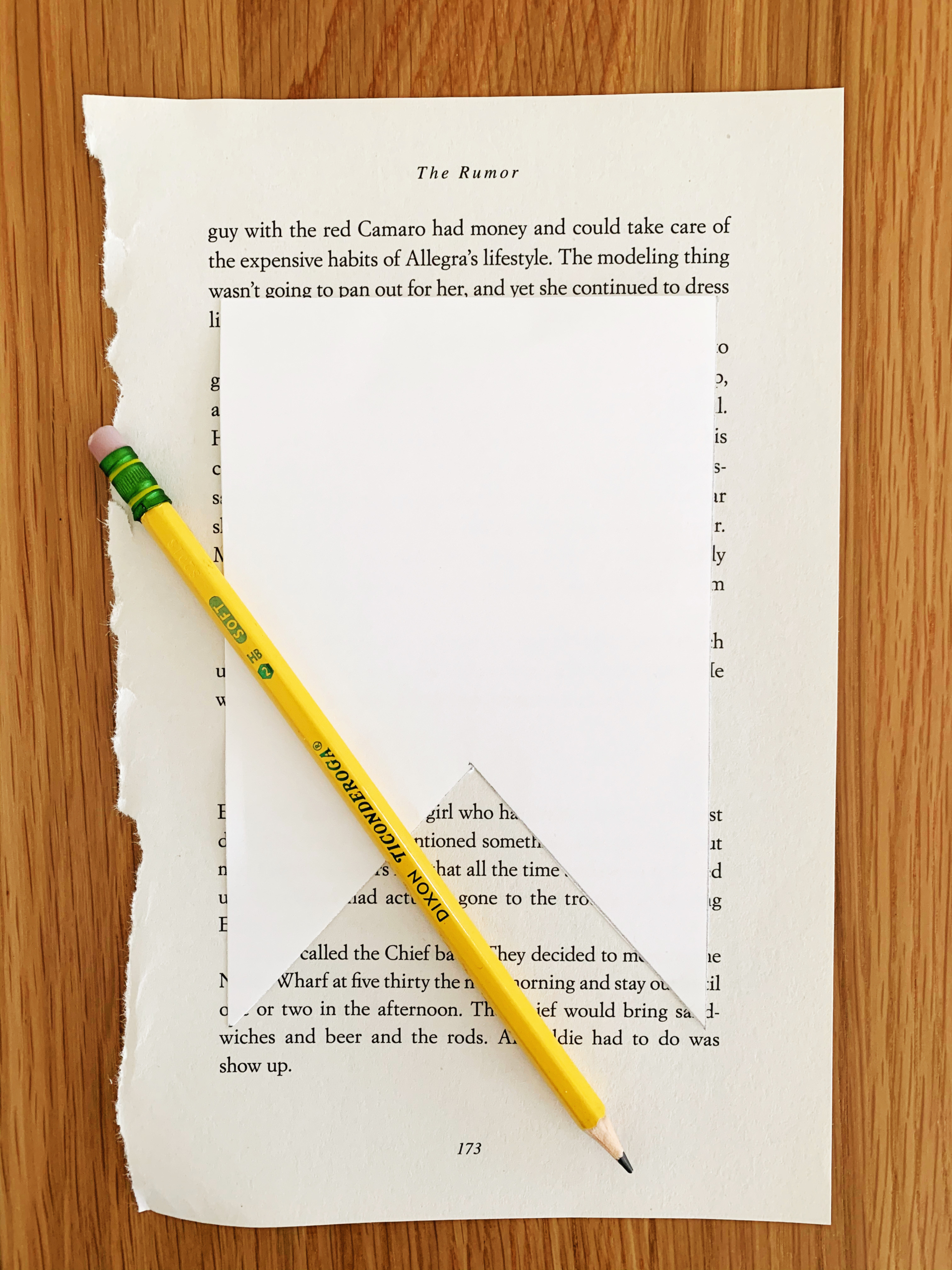

Step Two: Decide how many flags you want and cut out the book pages. I decided I was going to spell out r-e-a-d-i-n-g, so I needed at least 7 pieces. Using your template, trace the flag on the book pages and then cut them out.

Step Three: Write the letters of your message on the banner pieces. Alternatively, you can decorate your banner pieces however you would like. (You can also just skip this step and leave the book pages as they are!)

Step Four: Now you’re ready to attach the pieces to the string. Fold the top of each banner piece over (towards the back of the flag if you have decorated it), about ¼-½ inch. This is where your twine, yarn or ribbon will lay.

Step Five: Lastly, slip each banner piece over the string and secure the folded flap to the back of the banner piece with clear tape. That’s it. So simple! No glue and no mess. FYI, the flags will move along the string, so if you would rather they stay in place, just add a little piece of tape on top of the ribbon before you fold the flap over it.

You can make your book page banner as long as you want! Just keep adding banner pieces until you’ve reached your desired length. If you are spelling a word across the banner but want it to be longer, you can add as many banner pieces to either end as you like, add a blank piece between each letter, or draw something cute like a star or heart on the in-between pieces!

Hang up your banner and enjoy this sweet and simple DIY book craft!

Cooling down on a hot summer day has never been cuter! Kids will love this fun summer book craft to create their own personal fans. Made out of upcycled book pages, these sweet paper fans are easy to make and fun to use. You can keep them simple or get as detailed as you want in coloring and decorating them. Get creative with stickers, glitter, or whatever else you have on hand. You could even glue feathers along the top of your fan!

Once your fans are finished, you can store them in a vase on a porch or patio, ready for those hot days and nights. In the meantime, they’ll make a crafty and summery centerpiece. Or take them along to keep kids (or yourself!) comfortable on outings—just compress the accordion folds and secure them lightly with a rubber band or string to keep them from getting crumpled. However you choose to use them, these book page fans are a literary way to keep your cool.

Materials:

- Old book pages (six pages per fan)

- Decorative paper punches

- Tape

- Ribbon

Optional:

- Colored pencils, markers, or even watercolors

- Other items for decorating: stickers, glitter, feathers, or anything you have on hand

- Glue

Cost: If you have these basic supplies already on hand, this craft could cost you nothing! If you need to get a decorative paper punch, you should be able to pick one up for a few dollars. It’s worth having a few on hand for future crafting. (On the other hand, you could skip the punch and just get fancy with some other crafty touches.) We can usually find a bit of ribbon around the house, but if you can’t, you can always get creative by twisting a bit of tissue wrapping paper or using several strands of colorful yarn twisted together.

Step 1: To start off, take six old book pages. Trim the side that you tore out of the book for a neater edge if need be. If you want to color the fan or decorate it with glitter or small stickers, go ahead and do that now, but leave any larger details like feathers to add after folding your fan. You only need to color or decorate one side of each page. Tip: Don’t put anything on that will make it too hard to fold the paper (e.g., no rigid stickers), and beware of tearing the thin paper of your book pages when coloring or painting them.

Step 2: Because book pages are usually made of pretty thin paper, we’ll make the fans a little sturdier by doubling up the paper. So, take two pages together (if you decorated the pages, have the decorated sides face out) and use your hold punch to cut a row of shapes along the top of the book pages. Repeat for the rest of the pages (three sets total of two pages each).

Step 3: Keeping the pair of pages together, you are now going to accordion-fold across the page horizontally. Once you’re done with this step, you will have three sets of accordion-folded double sheets.

Step 4: Now you are just going to attach these three sets together to make one larger fan. With a few small pieces of tape, attach the outermost folds together.

Step 5: Lastly, gather the fan together at the bottom edge (the one without the shapes) and tape around all the folds. Then tie a decorative ribbon to cover the tape. If you’re planning to add larger adornments such as feathers, go ahead and glue them on now.

This fun and quick project is not only a crafty way to cool down on hot days, it’s also a great activity to keep kids busy (and cool!) during summer vacation. These adorable fans can even make cute favors for a summertime party. Let us know how you use yours!

Whether you’re hitting the beach with a vacation paperback or encouraging your kids through their summer reading lists, a bookmark is a must. Having a page-marker handy helps keep kids (or you!) from folding over the corners of those library and school books—or creasing up your home-library favorites. And these slide-on DIY corner bookmarks don’t get knocked out when you toss your book into a tote, the way traditional bookmarks can.

Make these cute pocket bookmarks with just some squares of paper and a little origami. Then decorate them however you like. This book craft is great for kids and all ages. Follow along the simple steps below and you’ll have a bookmark that fits right over the corner of your page in no time! Once you or your crafters get the folding down, you can churn out as many designs as you like. Fruit salad, anyone?

Materials:

- Craft paper

- Scissors

- Craft glue

- Pencil

- Colored pencils or markers

Cost: This craft should not cost you anything, provided you’ve got a few basic supplies on hand.

Step One: First you need to cut out squares to make your bookmarks. You will need one square for each bookmark. I made mine 5” x 5”. You could go bigger than this, but I wouldn’t go any smaller!

Step Two: Now we will start folding to make your first bookmark! These folds are pretty simple, so just follow along. First, fold in half, making a triangle.

Step Three: Take the top point of the triangle (just the top layer!) and fold it down towards the bottom.

Step Four: Fold the bottom left corner up to the top point of the triangle.

Step Five: Now do the same with the right corner of the triangle, once again matching it with the top of the triangle.

Step Six: You will now just take those points and fold them back down to the bottom, making a crease in the middle. Once you have the crease made, fold the paper back in the other direction, slipping it into the pocket created by the fold in Step Three.

Step Seven: Now for the fruit shapes: Take a spare piece of paper and trace the corner of the pocket you just created. You will just need to trace the bottom part. Once you have that drawn, just connect the two points with an arch to create your fruit slice!

Step Eight: And now it’s time for the fun part! Take your colored pencils or markers and color the shape you just cut out. You can follow along with my color patterns or create your own. I made a lime, a watermelon, and an orange.

Step Nine: Once you are done coloring, it’s time to attach your fruit shapes to the folded square. Take your glue stick and apply glue to the outside of the pocket. Then line up the pointed corner of your fruit and attach it to the outside part of the pocket.

That’s it! Now you are ready to kick off your summer reading with these cute bookmarks. Let us know how you decided to decorate your bookmarks. I can think of a few other fruits we could add to our collection!

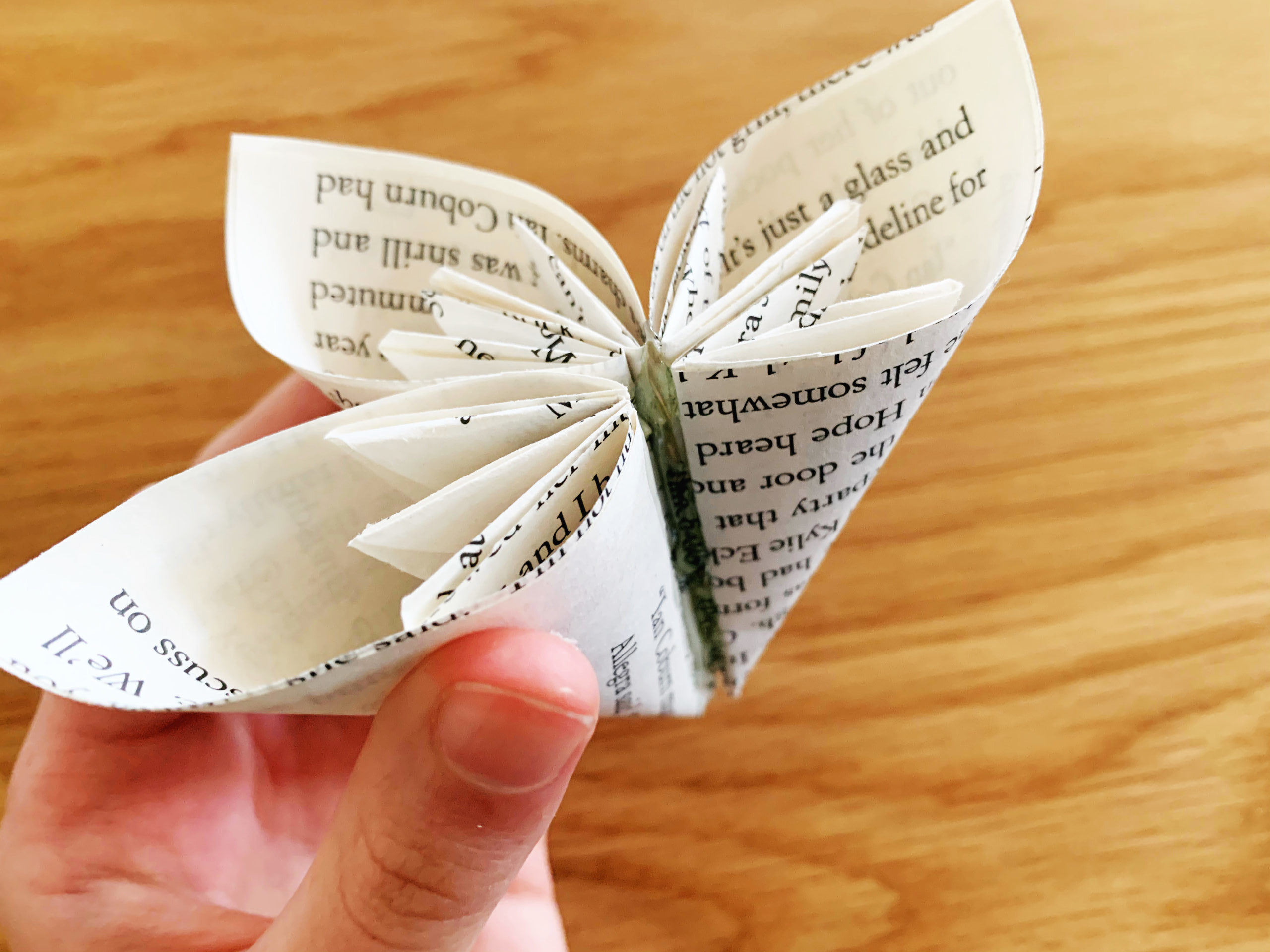

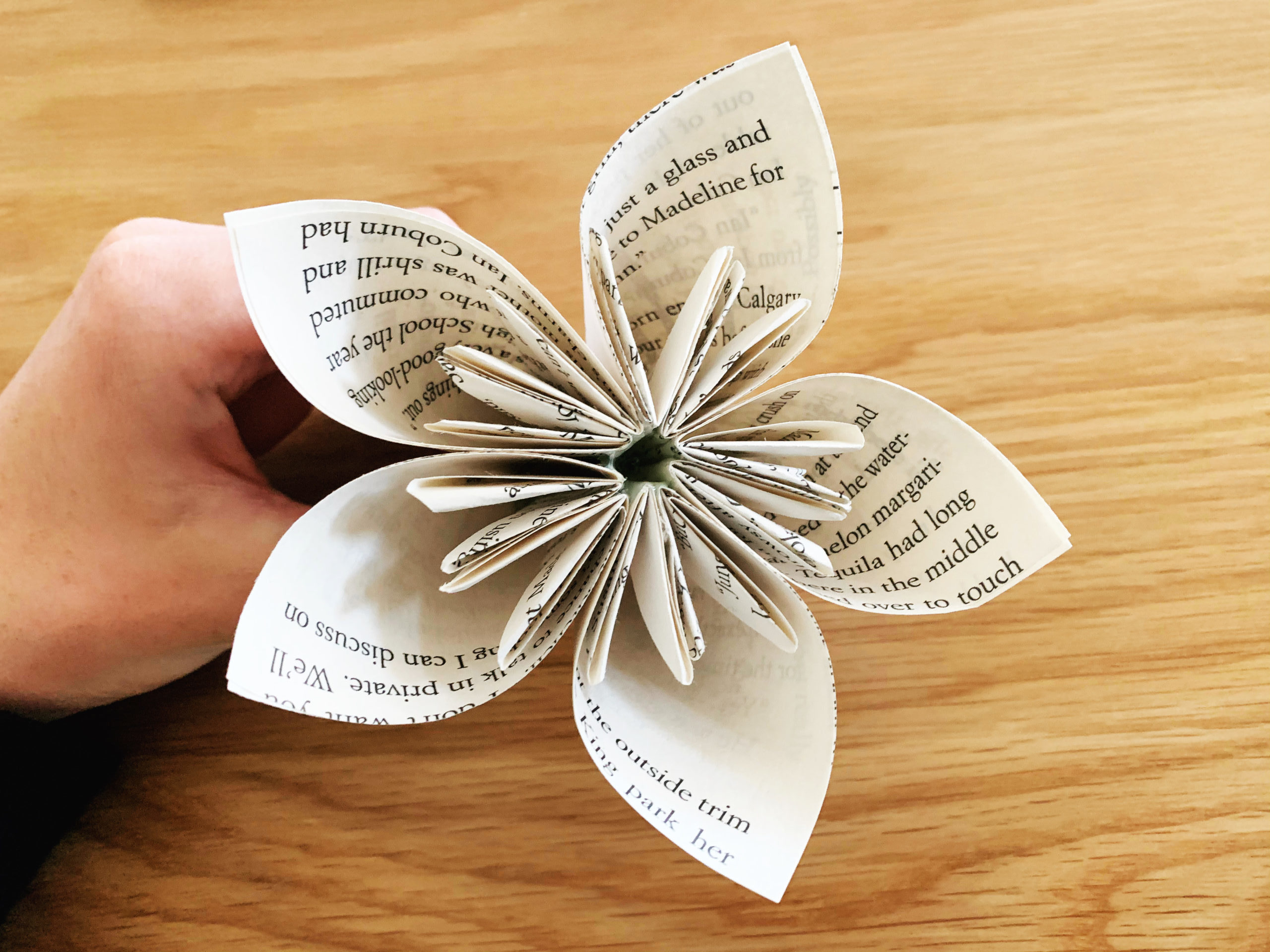

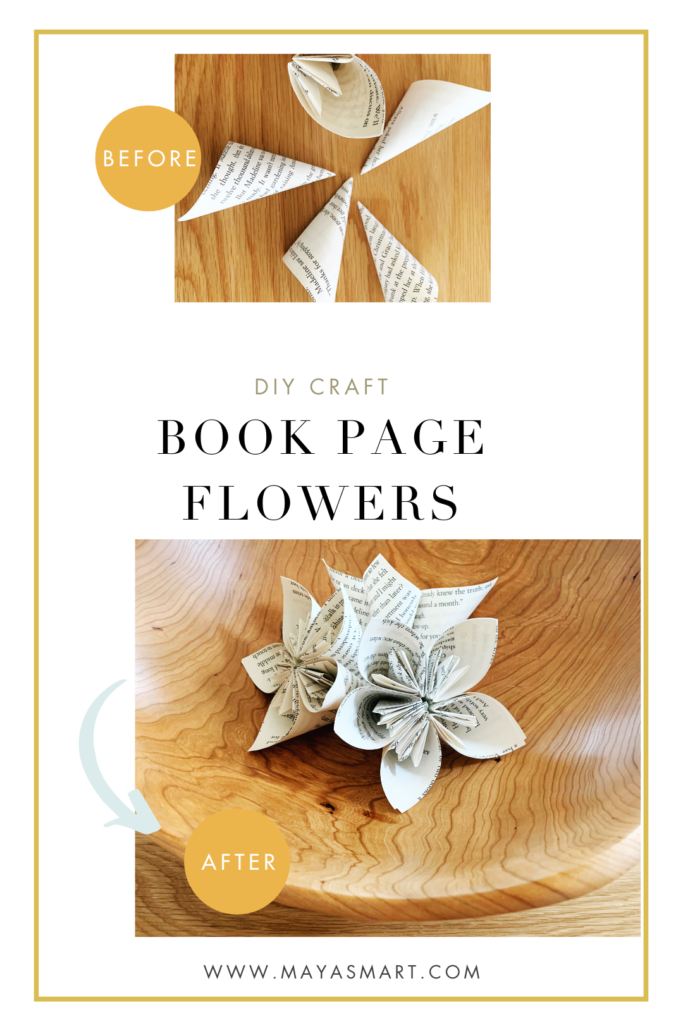

These literary blossoms are a fun craft to freshen your table or decorate for a special event. Display them in a natural wood bowl or scatter them along a surface for a sophisticated, minimalist effect. String them together along a streamer and hang them for a festive look. Or attach them to a small wooden dowel and put them in a vase—they can stand alone or add a cute touch to a bouquet of cut flowers. You could even get really creative and use them to top drink stirrers or a lit-themed cake.

However you use them, these DIY book page flowers are a lovely way to upcycle damaged or obsolete old books. There are many different patterns for book-page blooms out there (including our paper hydrangeas tutorial), and this one makes a particularly elegant flower. Once you get the hang of making the petals, this craft goes super fast. Kids can easily help out with this project. I recommend making it a fun assembly line to make the petals and then just helping them with the hot glue gun for the finishing touch!

Materials:

- Old book pages

- Ruler

- Scissors

- Pencil

- Hot glue gun

Cost: If you have a glue gun, this project shouldn’t cost you a thing! This is the perfect chance to upcycling old book pages into beautiful decorations.

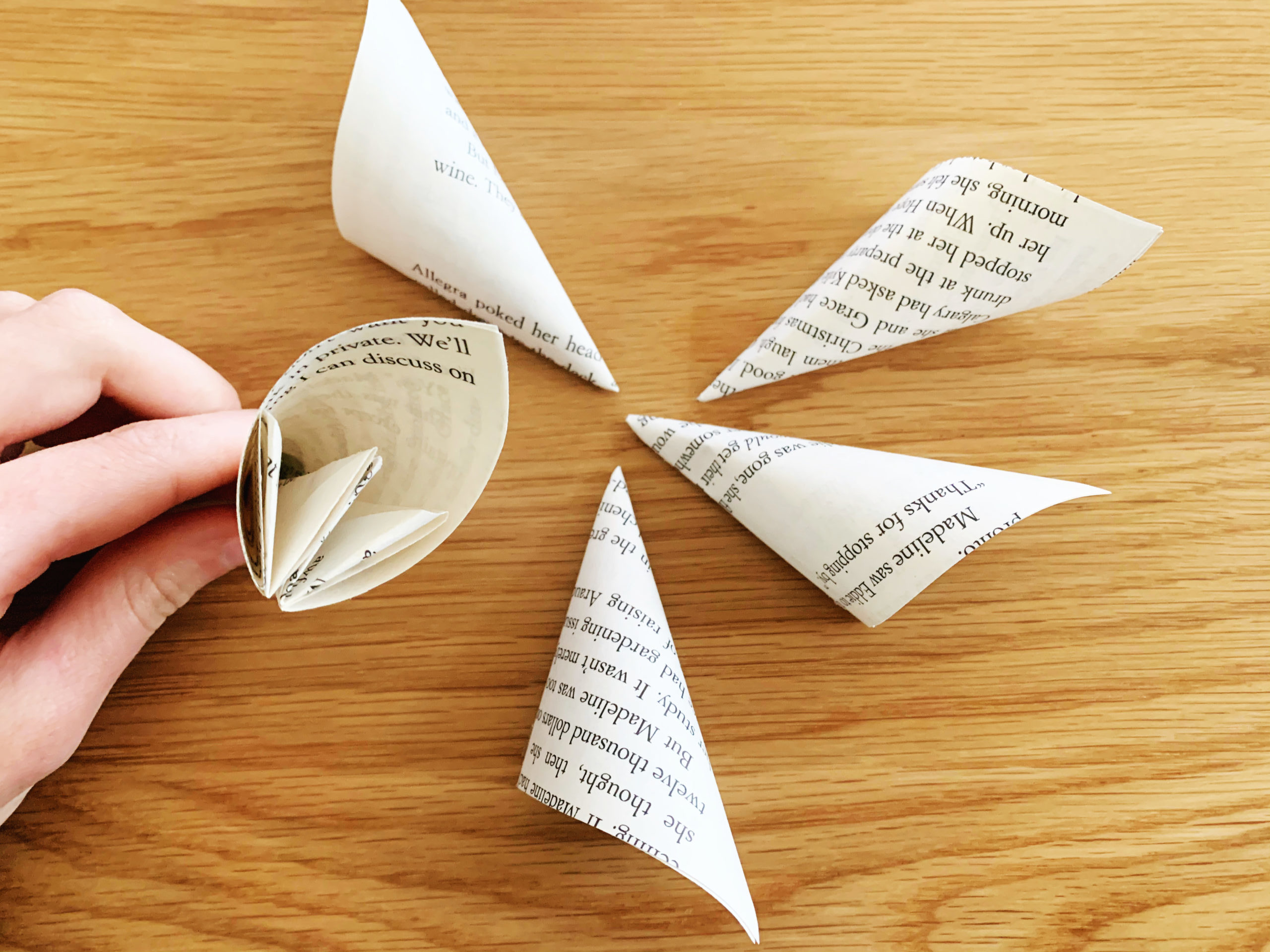

Step One: To start, you will need a perfect square from your old book pages. Each square makes one petal and you will need 5 petals per flower. I worked with 5” squares — but just remember, the larger or smaller your square, the larger or smaller your flower will be. If you plan on making a few, it could be fun to create a variety of different-sized flowers!

Step Two: The next set of steps are how to fold your petals. I broke this down step by step, so just follow along for each fold and you will end up with the perfect petal, and eventually, the perfect flower!

First, fold up one corner point to make a triangle.

Step Three: Fold over the right point up to the top.

Step Four: Fold over the left point to the top.

Step Five: Now take the top right point and fold it over towards the right, even with the side (see picture if this sounds confusing). Make a nice crease.

Step Six: Do the same for the left. Make sure to really crease these folds because you’ll need the crease lines as a guide in a few steps.

Step Seven: Take the right flap that you just folded over. Open it up with your pointer finger so that the side fold is now in the middle. Flatten it out and it will look like a kite.

Step Eight: And do the same for the left side.

Step Nine: Next, fold over the top of the “kite” so it’s even with the triangle’s sides. Do that on both sides.

Step Ten: Now take the sides and fold it over towards the center. You will already have a crease here from your earlier fold (this is what I was talking about earlier!).

Step Eleven: Next, “curl” up both sides to meet. Don’t crease this part. You want it rounded like a flower petal.

Step Twelve: While pinching the edges together with one hand, with the other take your hot glue gun and glue the sides together. You now have your petal!

Step Thirteen: Repeat steps 1-12 until you have your five petals. Once you get the hang of it, these petals are super easy to make, I promise!

Step Fourteen: Now that you have your five petals, it’s time to glue them together to make your flower. Start with 2 petals and glue the edges together. Once that glue dries, add another bit of glue to the edge and add on the next petal. Just keep adding all your petals in this pattern and you will be holding a full flower before you know it.

And you’re done! I chose to arrange the three flowers I made in a bowl, but there are so many different ways you can display these blossoms around your home. Let us know how you decide to decorate with them; we’d love to see what you come up with!

By Karen Williams

Showing support for independent bookstores is a noble cause, and a common way to do so is to simply visit the bookstore itself. But you can show support from home, too. Whether your goal is to avoid the crowds or get to know a bookstore outside your region, there are several ways you can support your favorite bookstore virtually.

Buy books from online storefronts.

Now more than ever, your favorite independent bookstores need your business. Many bookstores have the ability to sell books online for home delivery. Or, local stores may have a curbside delivery option where you can browse online and then drive by for pickup.

If your local store doesn’t have an online shop or you’re interested in browsing elsewhere, check out Bookshop.org, an ecommerce site with a mission to financially support local, independent bookstores. Booksellers, authors, and literary publishers (like this site) affiliated with Bookshop earn commissions on sales. Additionally, 10% of regular sales are added to a fund that is evenly divided and distributed to independent bookstores every six months. The site launched in January 2020 and by June had contributed more than $3 million to bookstores!

Purchase gift cards.

If you’re not in the market for new books right now, consider buying gift cards from indie booksellers for the future. You can always use them at a later date, or give them to the book lovers in your life for them to use as they please.

Buy audiobooks.

If you prefer to listen to your books, check out Libro.fm, an audiobook service where you can purchase directly from the independent bookstore of your choice. Libro has partnered with hundreds of bookstores across the county. If you don’t see your favorite store on the list, just contact Libro and they’ll be happy to work with your store to get started selling audiobooks.

Tag your favorite location in social media posts.

Subscribe to your bookstore’s email list. Many stores offer coupons and deals for their email subscribers to use. When you follow their social media pages on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Pinterest, you are also showing your support to your friends and followers. Share what makes your favorite store special, and use hashtags like #bookstore, #books, #reading or #bookworm so that other readers can discover the store you love.

Leave a review.

Spend a few minutes writing a review on Google, Yelp, or Tripadvisor. Not only do positive reviews help your favorite bookstore get exposure online, they also give potential customers the chance to learn more about your favorite spot. It’s a win for everyone!

Attend a virtual event.

Many bookshops are offering virtual events that you can attend from the comfort of your home. Participating in online book clubs, workshops, and author readings is a great opportunity to support your indie store with your presence.

Make a donation.

If your indie store is a non-profit organization, contact them to see if you can donate to show your support. Or, consider supporting bookstore owners with a donation to the Book Industry Charitable Foundation, an organization that helps independent booksellers and their families facing financial hardship.

Even in thriving economic times, independent bookstores face challenges. Competition with larger retailers, small profit margins, and overhead costs present an uphill battle for the bookstores we love. Any small step you can take to support your bookstore virtually can make a huge difference. What can you do today to show your love for independent bookstores?

Many parents, especially bookish ones, long for their children to fall in love with reading. They read to their kids religiously, awaiting the day when their children take pleasure in selecting and reading books on their own. They hope that curling up in the company of a great book will beat out apps, games, and screen time on their kids’ list of preferred activities.

But, alas, kids often show greater interest in other things. I know that my own daughter’s reading interest and motivation ebbs and flows. There are weeks when she’s more excited about making slime (again), building a pillow fort (again), or even practicing her typing than reading a book. And there are other times when she’s rolling through a series of books, pausing only to tell me the author’s life story and when the next installment is set to drop.

Over the years, I have observed a few factors that seem to boost reading enjoyment. Here’s my best advice for parents who want to encourage their kids to read more on their own.

Shore up their Reading Skills

It’s no fun to read when you struggle with it, so parents of kids who aren’t exhibiting much book love should make sure that there’s not an underlying decoding or comprehension challenge in play.

Take a look at your state’s reading standards to familiarize yourself with grade-level expectations and initiate conversations with your child’s teacher about the students’ strengths and challenges. You could also seek a full-fledged learning evaluation from your school district or an independent provider to discover how your child performs on standardized academic and reading assessments. Detailed evaluations can let you know where your child needs additional support to bring the words on pages to life.

Studies indicate that early reading skill matters for later reading skill and motivation, so make it a priority to secure a strong literacy foundation now.

Supply Interesting Reading Material

Assuming your child can decode and comprehend the texts available to them, the next most important parent action is to give them ample access to interesting (to them) reading material of all kinds—print or digital books, magazines, recipes, lists, instruction manuals—whatever they’ll read attentively. Along with skill, enjoyment is great fuel for reading volume, so stock up on material related to your child’s interests.

One of my favorite examples of this approach is a parent who bought Minecraft books to complement a child’s obsession with the game. “I’ve found that far from increasing time spent on Minecraft, getting your Minecraft fan a book about Minecraft seems to actually have no other effect than to increase the time they spend reading,” the parent observed. “With enthusiasm. As in, I don’t even have to nag them to read. They, gulp, seem to actually WANT to read.”

Epic Digital library is a great choice for families in need of fresh reading material. This kid-focused library offers thousands of ebooks in an ad-free, immersive environment for children 12 and under.

Remember, it’s never the time to force your literary tastes on your child. As long as the content they enjoy isn’t racist, violent, or otherwise objectionable, let them read what they want on their own time, because that literacy practice can boost their reading fluency, vocabulary, and stamina. This is what I tell myself when my daughter is more into magazines and books based on her favorite TV shows than the children’s literature I prefer.

Make it Social

I’ve witnessed firsthand how my daughter’s reading enjoyment is enhanced by factors beyond the book itself—like who shared it with her or who else is reading or talking about it. In kindergarten, she read every available installment of The Owl Diaries because her friends were reading the series too. They had a little book club, traded copies, and shared the excitement of tackling their first chapter books together. I’m convinced that the community around the book kept her reading the series longer than the plot or characters alone would have.

Do any of these strategies resonate with you? What have you tried to boost your child’s interest in reading and how did it work?

These DIY fabric book covers are a pretty and crafty way to protect your library. Safeguard books while traveling, replace lost dust covers, or preserve well-loved titles from eager (and grubby) little hands. We especially like these covers for keeping kids’ favorites in good enough shape for them to read to their own children someday. Plus, they add a fun pop of pattern and color to your bookshelf.

This book craft is easy, inexpensive and doesn’t take long. Have leftover fabric from other DIY crafts? Perfect! You can use different patterns for variety, or make multiple covers from the same material to create unity in the decor of your library.

Materials:

- Hardcover book to cover

- Fabric

- Fabric glue or tape (or you could use a glue gun)

- Sharp scissors/fabric scissors

- Tape measure

- Ruler

- Pencil

Cost: If you have some fabric around (or an old curtain, sheet or garment to cut up), this book craft should not cost you anything. This is the perfect way to use up a smaller scrap!

Step One: The first thing you will need to do is cut out your fabric piece. To do that, you will need to measure your book, so you can cut a piece that’s the right size. Measure both the height of your book and the “wrap-around” width of it from edge to edge with the book closed.

Step Two: Now you’re ready to cut your fabric. Cut a piece of fabric that’s 1 ½” taller than your height measurement and 8” wider than your width measurement.

Step Three: Once you have your piece of fabric cut out, place it down in front of you with the unfinished side facing up. Measure 1 ½” from the top and bottom edges (the long sides) and draw a line lightly with your pencil. Then make a line 4” in on either side (the short sides), marking the part that will become the pockets where you will eventually slide your book in.

Step Four: Now it’s time to create a “finished edge” along the top and bottom. Place some glue between the raw edge along the top of your fabric and the pencil line you just drew (1 ½” below), leaving the last 4” to either side unglued. Then fold the fabric over so the raw edge meets the pencil line. Repeat for the bottom edge.

Step Five: Next you will need to create the pockets for your book to slide into. Measure 8” from either side, making your marks on the part of the fabric you just folded over. The first 4” of this fold will be the part that you just left unglued in the previous step. Place glue along the finished part of the seam only, and then fold the side edge over to meet the mark you just made at 8” in. Your book cover will still be able to slip under the fabric because your first seams are not glued! Press it down gently, being careful not to let the glue seep through the fabric and accidentally glue together the unglued part.

Step Six: All that is left to do is let your glue dry and then slip your book into your beautiful new book cover!

This can be a fun craft to do with kids as well! They will love dressing up their favorite books and pulling them off the shelves for storytime. How will you use your new book covers?

These might be my new favorite DIY craft bookmarks! The chunky tassels are so fun and make it super easy to find your spot in a book, even for little hands. They’re also eye-catching and hard to misplace … hopefully encouraging young readers to use them instead of folding down the page corner! (We can always dream.)

This is an excellent book craft to do with kids. Let them draw or paint their own design to personalize their bookmark, or help them copy out a quote from a favorite book to add some extra literacy to the project. And don’t forget to have them to sign their creation! Whether you’re doing it to create a cute keepsake or as the perfect made-by-me gift, this simple craft is satisfying for all ages.

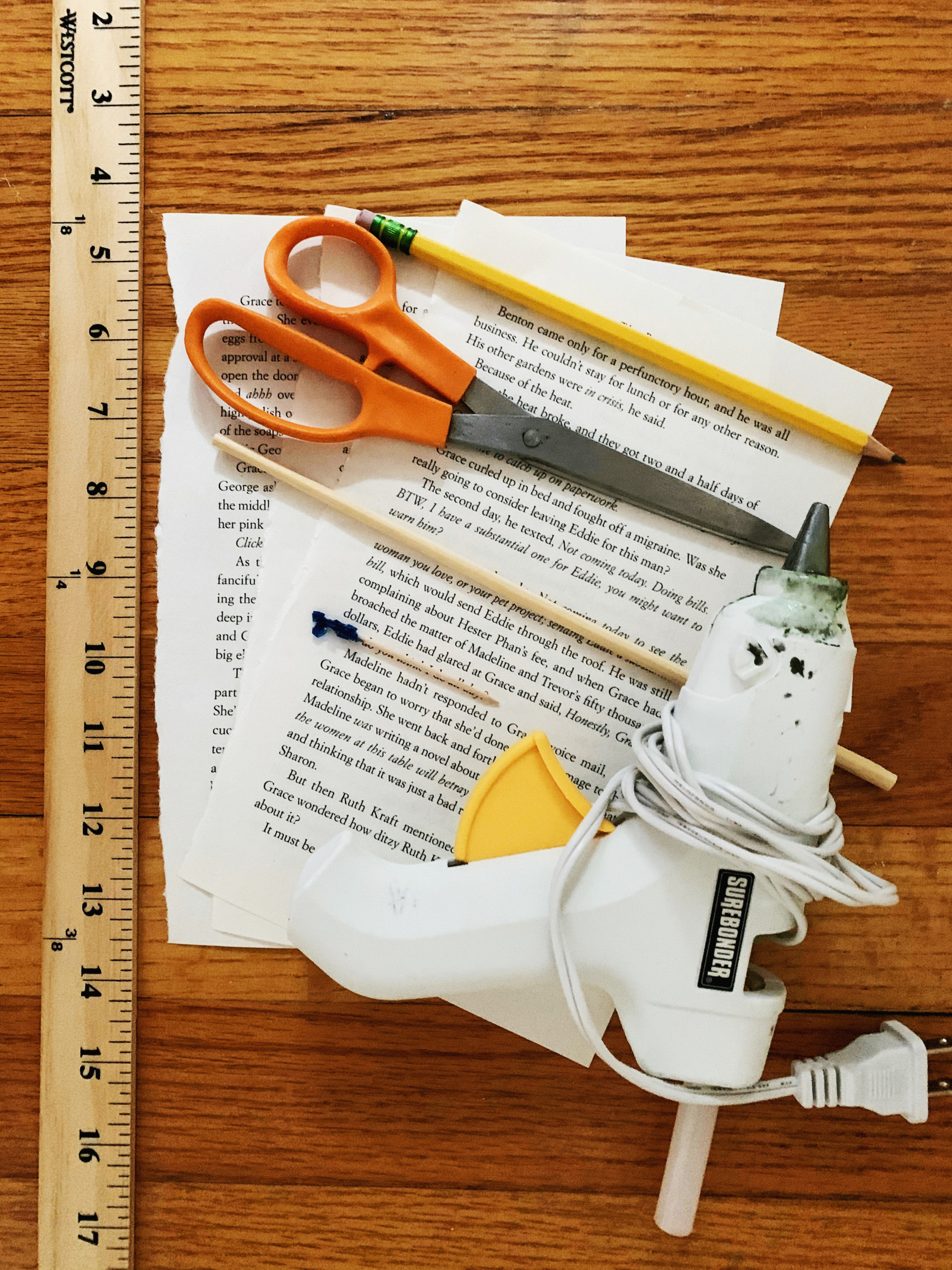

Materials:

- Yarn

- Scissors

- Cardboard

- Ruler

- Pencil

- Cardstock (patterned, or plain to decorate your own!)

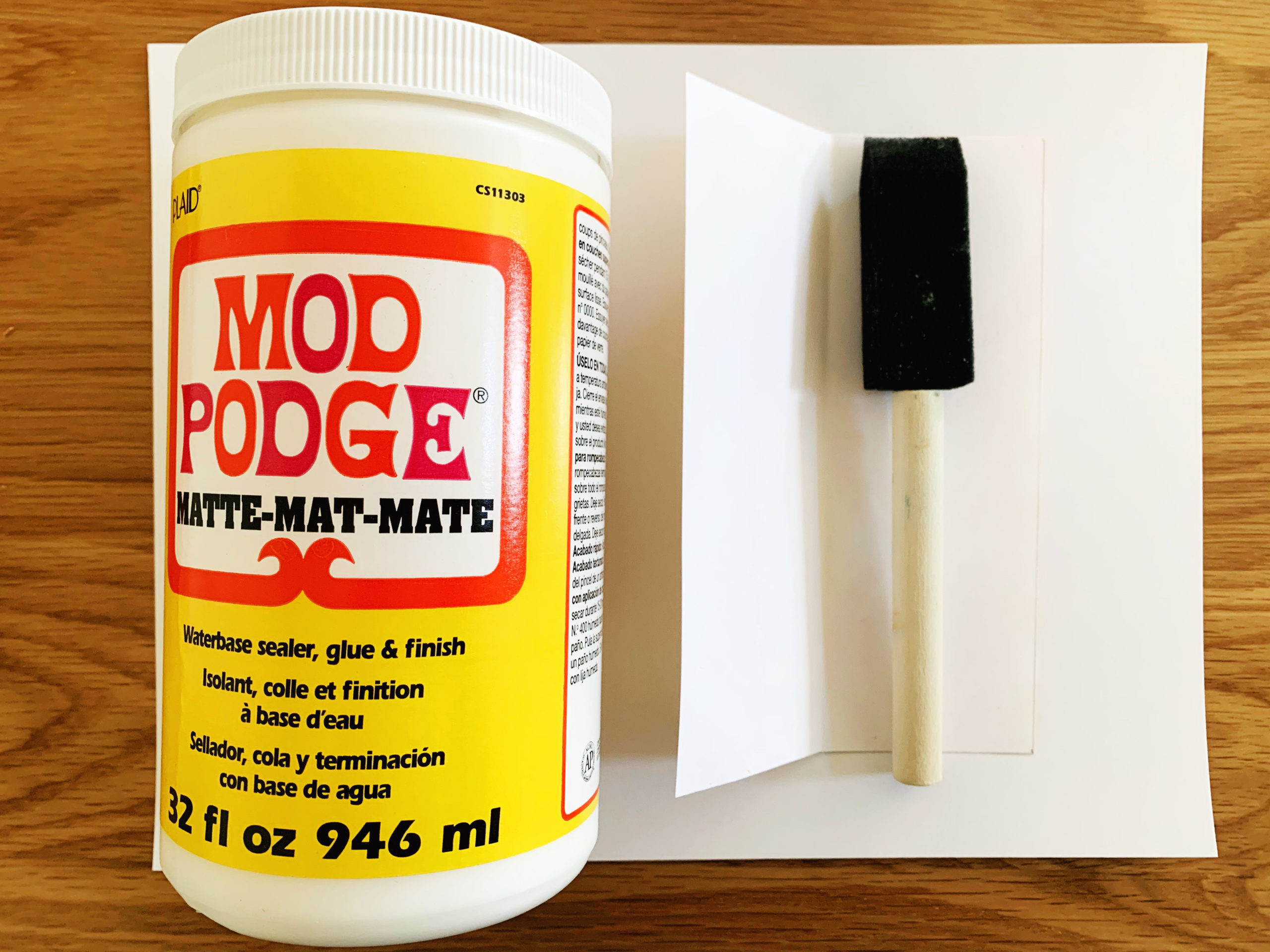

- Mod Podge (or other glue)

- Foam brush

- Hole punch

Cost: You probably have most of these materials around your home! If not, the cost will be very minimal to get a few of these craft supplies, which you can reuse for another project.

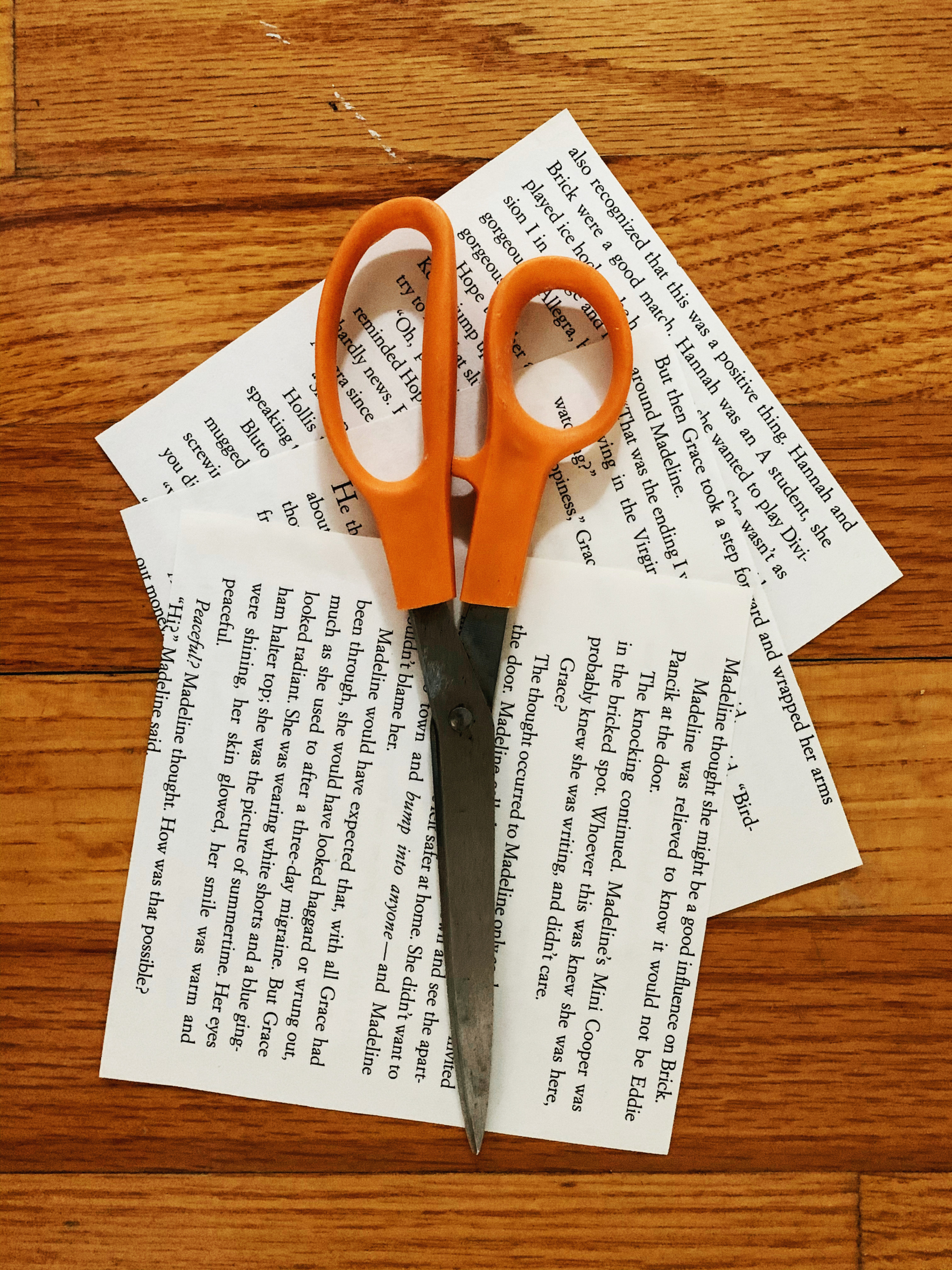

Step One: Cut a piece of cardboard to about 3.5 inches wide.Take your yarn and wrap it about 50 times around the cardboard. Then cut the yarn from the spool.

Step Two: Cut a small piece of yarn from the spool and slide it under all the yarn on one side of the cardboard, as shown below, then double knot it at the top.

Step Three: After you tie the knot, cut through all the yarn on the opposite side.

Step Four: Now, to finish off your tassel, cut off two small pieces of yarn from the spool. Wrap the first piece around the top and tightly double knot it to make the head of the tassel. Repeat this with your second piece of yarn, underneath the previous piece of yarn.

Step Five: Trim any straggly pieces of longer yarn from the bottom of your tassel, to clean it up and make it look even.

Step Six: Measure and cut out a 4.5”×6.5″ piece of cardstock. If you’re decorating your own bookmark, now’s the time to decorate it. (I chose to decorate my own rather than using a patterned cardstock, but you can definitely use patterned paper, especially if you want to make several bookmarks.) Once you have cut it out, fold the cardstock in half lengthwise.

Step Seven: Apply a thin layer of Mod Podge (or glue) with a foam brush on the inside of the cardstock, then fold it together and let it dry.

Step Seven: Once it is dry, punch a hole at the top of the bookmark. Double knot the tassel through the hole, cut off the excess yarn and you’re done!

I hope you enjoy making these tassel bookmarks as much as I did! Let us know what book you’ll be using your new bookmark with next. We’d love to know what’s on your reading list!