Parents are uniquely positioned to help kids build reading and writing skills that are best developed little by little over many years. So a central tenet of the Maya Smart approach to raising readers is helping children learn through what we like to call everyday literacy. This can mean pointing out words on cereal boxes and chatting about letters on street signs. It can mean including reading and writing in family travel and road trips, or emphasizing words on kids’ clothes. It can mean working literacy skills into special occasions, to make a celebration like Halloween a reading holiday, for example. And so much more.

In line with this idea, we decided to make it easy to mix reading and writing practice into another important activity with children: feeding them. Let’s face it, making and serving endless meals and snacks is an ever-present element of parenting. And bringing the kids into the action, by inviting them to cook with us, is both a great activity in its own right and a time-tested way to up the odds they’ll actually eat what we prepare.

That’s why we created the Read with Me Recipe series of kid-friendly snacks and meals that are super easy to make with kids—presented in a format that’s also easy to read with kids. Think simple words and short sentences that will set your little one up for success. What’s more, each recipe is optimized to highlight a specific spelling pattern or reading ability, so you can introduce and reinforce key skills in small, playful doses with each dish you make.

The idea is for you to print out the recipe and then read it with your child as you prepare a simple, frustration-free dish together. Each one comes with teaching tips for using the recipe to build specific knowledge and skills with beginning readers. That said, you can also use these recipes with pre-readers, as a way to introduce them to written language. Just read the recipe aloud to them and draw their attention to some of the elements, such as any incidences of their first initial or another letter they may recognize. (Scroll down for more tips on using the recipes to teach.)

*Important note: Adults should be closely involved in the cooking, from chopping to using a hot stove, to ensure safety.

MayaSmart.com’s exclusive kids’ cookbook PDF includes the full collection of Read with Me Recipes. You’ll find a variety of simple snacks and meals popular with kids and even some special holiday recipes. Here are the dishes inside (plus the skills they’re optimized for):

- Cake in a Cup: Silent E

- Carrot Hummus: Double Consonants

- Cheese and Chicken Pasta: CH Digraph

- DIY Christmas Ornaments: Letter C

- Cool Fruit Smoothie: Double OO

- Easter Egg Bread: Long and Short E

- Latke Potato Pancakes: Compound Words

- Roasted Pumpkin Seeds: Double EE and OO

- Strawberry Sticks: ST Consonant Blend

- Stuffed Shell Pasta: SH Digraph

- Three Bean Salad: TH Digraph

- Yogurt Bark: Y as a Consonant (and Vowel)

Here’s how to use the recipes:

- Print out the recipe (or bring it up on a screen large enough for easy reading).

- Look at it together and draw your child’s attention to the specific spelling patterns or words highlighted in the teaching tips for that recipe, if your child is ready for it. If they’re ready, encourage them to find and circle or underline all the incidences of the specific pattern.

- Read and follow the recipe together. Watch out for any words they may not be familiar with, and give a simple definition.

- If they’re taking the lead on the recipe, be ready to gently help with any words they struggle on. For example, if they have trouble reading applesauce, try covering half the word and help them sound out one half at a time, then put both together.

- Bring your patience. Give your child space to figure out words or identify letters before you jump in, but be prepared to help if they’re showing signs of frustration.

- For little ones who aren’t reading yet, just read each step out loud, pointing to the words as you go.

- If they don’t know their ABCs yet, point out a few key letters in the recipe, like their first initial. Ask questions: Can you find a letter T? What letter does this word start with?

- If your child knows their letters but isn’t reading, point out some simple words to them, or help them try sounding out some of the simplest words.

- You can also use the recipe as an opportunity to introduce or reinforce punctuation. Point out and explain the use of periods, commas, or other punctuation marks.

Bon appétit!

P.S. If your child loves cooking, you’ll definitely want to check out our roundup of great picture books about cooking for kids. Each one includes a recipe to try out with your little one, too!

Is your little one struggling with reversing the letters b and d? If so, you’re not alone. It’s a very common challenge because—let’s be real—the two letters look just alike. Both have a long line and a curve. The difference is just their orientation on the page.

But that doesn’t mean parents should be passive about addressing b and d reversal. Luckily, the solution is simple too: Spend some time focusing your child’s attention on how the letters are made, giving them opportunities to write or make the letters (including with playdough, sand, or other tactile letters), and (most importantly) talking about their differences.

The time your child spends thinking about, discussing, and forming the letters makes a huge impact. With daily practice (for just a few minutes), these tried-and-true activities may help kids get b and d straight within just a few weeks. Plus, the exercises will feel like play, not like addressing a problem.

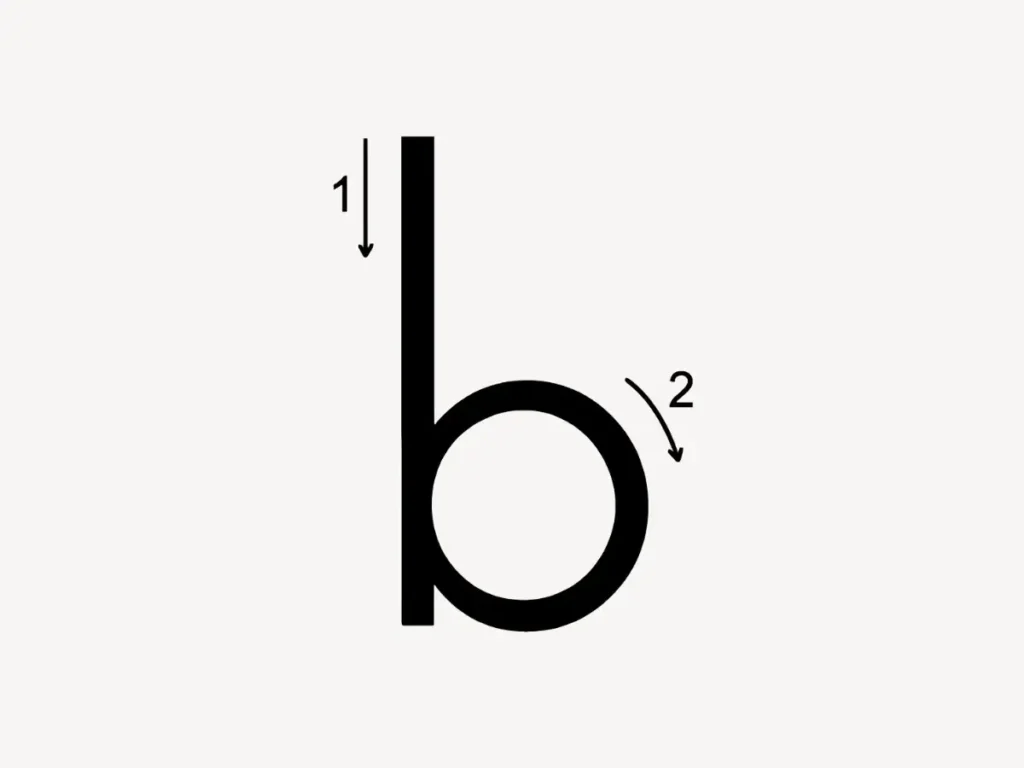

Show and Tell – Start at the beginning by showing your little one how to correctly form the letters. Narrate the starting point, the sequence, and the stroke direction. Get a blank piece of paper, white board, or tool of your choice, and have your child watch you write a lowercase b. Describe what you’re doing by saying, “This is a little b. I write it by drawing a long line down and then circling around to add the curve. See the long line here (tracing from top to bottom) and see the curve here.”

Then have your child write a lowercase b. Make sure they form it correctly, starting in the upper left and drawing down, then curving around. Don’t assume that they know this. Kids sometimes start with the curve or from the bottom of the letter. If needed, demonstrate the flow again, while describing it: “Start here. Go here. Then here.”

While they are writing it correctly, narrate what’s happening again. “See how you made the long line here (tracing from top to bottom) and then added the curve here? That’s a little b.”

Then do the same for d. Note: This does not have to happen in the same session or sitting. You can facilitate opportunities to compare and contrast the letters anytime, so don’t rush if your child isn’t yet solid with lowercase b alone.

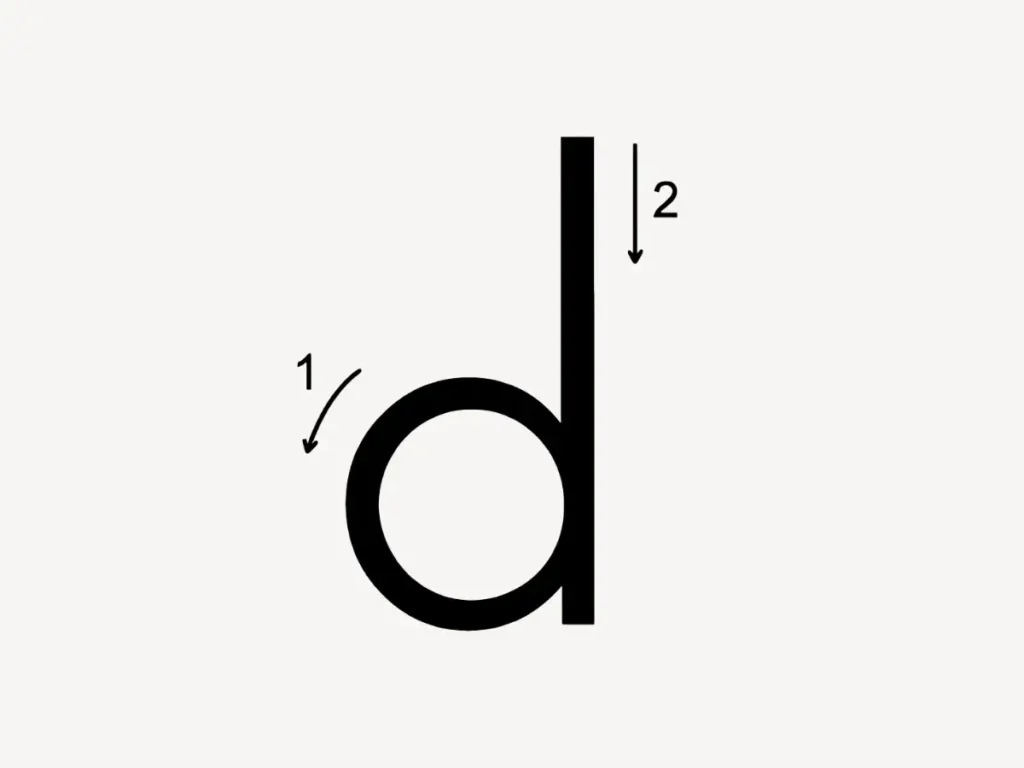

Have your little one watch you write a lowercase d. Describe what you’re doing by saying, “This is a little d. I write it by drawing a little curve then drawing a long line down beside it. See the curve (tracing the curve from top to bottom) and see the long line here. You have to make a little c and turn it into a little d.”

Then have your child write a lowercase d and make sure they form it correctly, starting with the curve. Watch carefully to make sure they’ve got the starting point, sequence, and stroke right. If needed, demonstrate the flow again and while describing it: “Start here. Go here. Then here.”

Have them write it a few times and narrate the process as they go.

Once your child has some practice naming and writing both letters, ask them:

- Where do you start writing little b?

- Where do you start writing little d?

- What’s the same about the parts that make up little b and little d?

- What’s different about how you write little b and little d?

Give Them a Hand

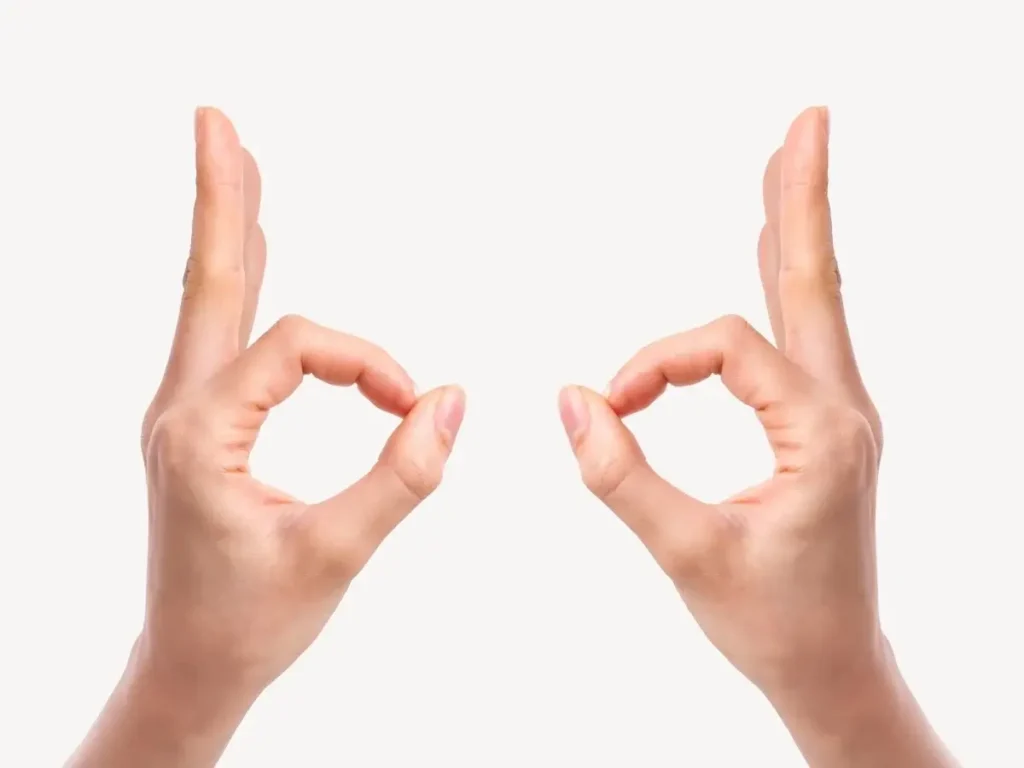

If your child knows that B comes before D in the alphabet (Thank you, alphabet song!), you can use that knowledge to give them a handy tool for highlighting the different orientation of the lines and curves in the two letters. Have them make a couple of okay signs but with the raised fingers held together. The hand signal create open space within the curve and long lines just like the letters. See the photo below. (Incidentally, you can also use this to teach them how to set a table. Bread plate on the left. Drink on the right.)

Tap their left hand and tell them that’s the B hand, because it’s first (as they look at their own hands) and B comes before D. Then tap their right hand and tell them that’s the D hand, because it’s second. Don’t use the words left and right. That just adds another layer of complexity to the exercise. The point here is to get them to focus on the letter shape, pay attention to the lines and curves, and give them the proper name.

Once they’ve got this down, they can always make the shape with their hands and compare that against the printed letter to know if they are looking at a B or a D or to check their own writing.

Make Your Bed

An advanced technique is to teach using the word “bed.” Only use this with kids who can blend common letter sounds into simple words. Draw a side view of a bed with head and foot boards and superimpose lowercase B and lowercase D over it. See diagram.

If your child continues to struggle with this after you’ve spent considerable time working on it and they are nearing 7 years old, then it’s time to seek out additional support. In very rare instances, the letter reversal may be a sign of visual processing or memory issue, so talk to your child’s pediatrician or seek out support through your local school district if the problem persists.

Like this post? Please share it!

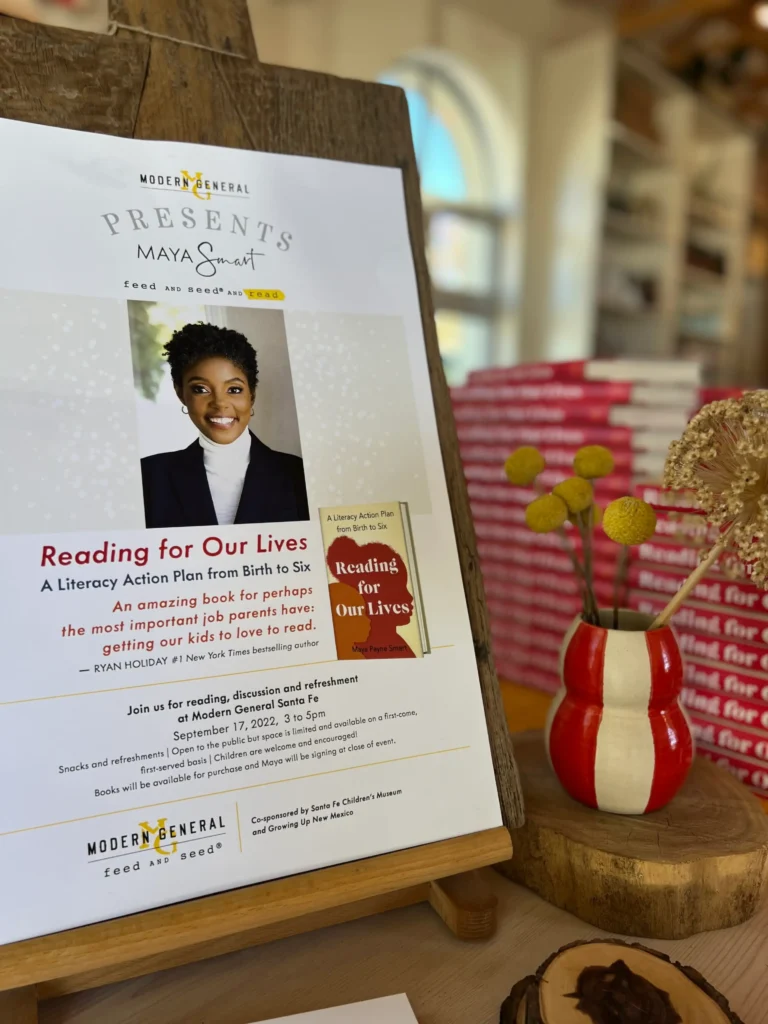

Picture this: A stage set with a seven-foot tall book, a bank of soaring windows revealing downtown Milwaukee’s skyline, and an energetic crowd of businesspeople, educators, and philanthropists.

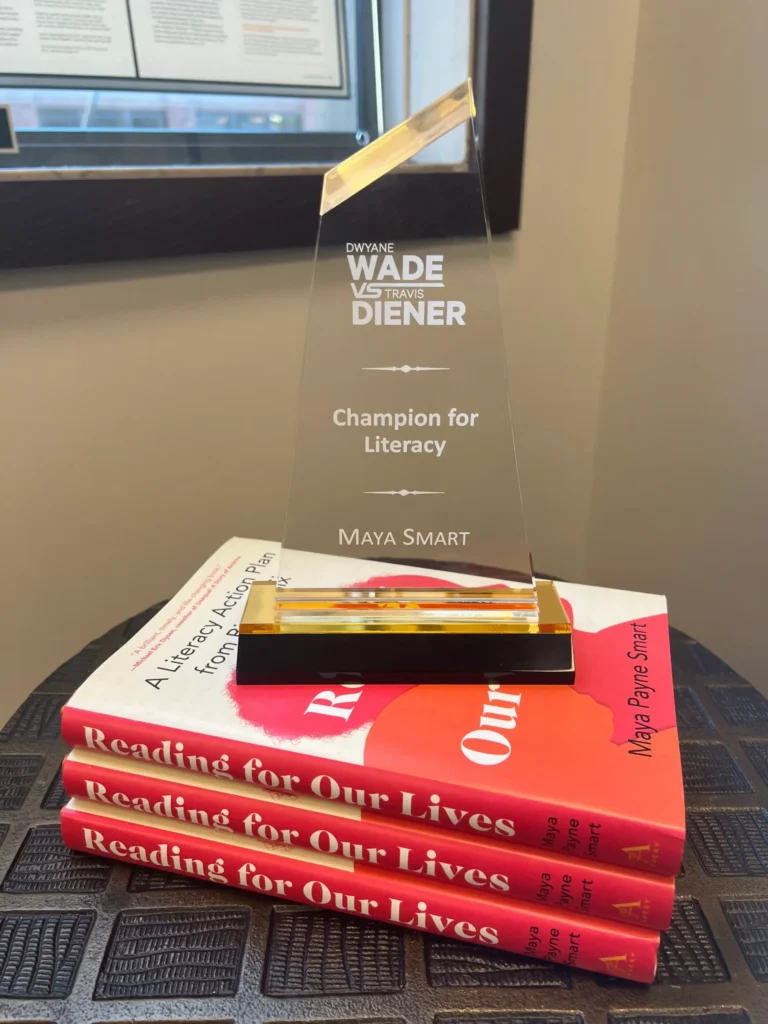

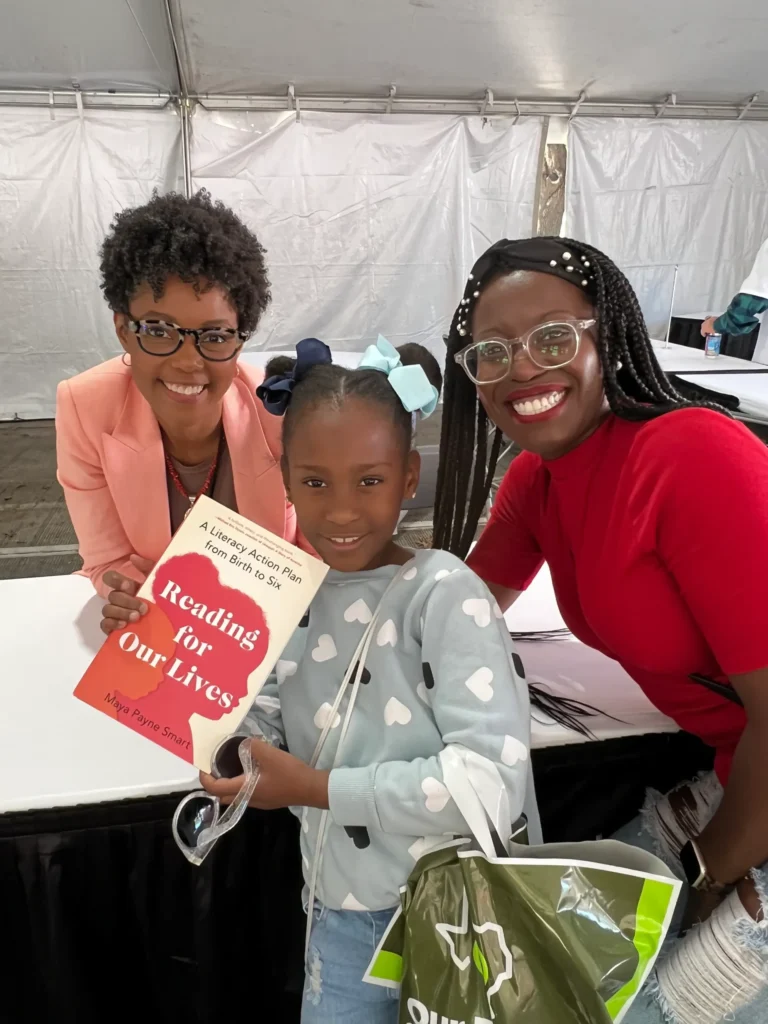

Just days before my book Reading for Our Lives toasted its first anniversary, I was at this event to be honored as a Champion for Literacy by former NBA stars and Marquette University basketball legends Dwyane Wade and Travis Diener.

No ordinary honor roll, this celebration was part of a sporting three-day Wade vs. Diener showdown, where the pair faced off to do the most for local children. They leveraged their famously competitive spirits to outdo one another in raising funds and awareness for vital youth programs, including the Tragil-Wade Johnson Summer Reading Program at Marquette.

From the stage, I looked around and saw an impressive group assembled. Without exception, the donors and attendees were people with many accomplishments and abilities–including the crucial but easily overlooked skill of able, fluent reading.

They were the kinds of people who can graduate from college, navigate the workforce, buy homes, vote in elections and (mostly) understand the bonds, levies, and referendums listed on the ballot. The kind of people who attend fundraising events for important programs like this one.

In many ways, the attendees’ successes were very apparent. What no one could see, though, were the thousands of relationships and experiences that contributed to all of our reading (and life) success. No one could see the parents or grandparents who read to us. The early caregivers who gave us the words to describe our environments, thoughts, and emotions. The teachers or tutors who painstakingly taught us to connect sounds and letters.

And that’s part of the challenge of ensuring literacy for all. There’s so much that goes into reading success that we don’t see. When we spend most of our time among readers, it’s hard to imagine the magnitude of people who struggle to make sense of street signs, product packaging, and the basic print of everyday life.

So I applaud Dwyane Wade and Travis Diener for using their platforms to highlight this challenge and raise funding to support the direct, structured teaching of reading to kids who need it most.

I thank them for creating space to grapple with this critical issue in Milwaukee, which offers a microcosm of our nation’s reading woes.

Wisconsin has the widest reading-score gap between black and white students of any U.S. state –a 50-point gap, according to the U.S. Department of Education. There’s also a 35-point gap between Hispanic and white students and a 33-point gap between lower- and higher-income students.

Only 12% of all fourth-grade students in Milwaukee (and just 5% of the black ones) read proficiently, leaving thousands on track to join the ranks of the 1 in 4 Milwaukee County adults who are functionally illiterate, per the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC).

And we have ample research documenting the ways that low to no literacy creates a direct pipeline to joblessness, homelessness, hopelessness, poverty, crime, and pretty much every other social ill you can imagine.

That’s why efforts like the summer reading program that the event supported are so important.

How a Summer Reading Program Addresses the Crisis

The teachers, administrators, and mentors of the Tragil-Wade Johnson Summer Reading Program led by Dr. Kathleen Clark do incredible work to serve dozens of children.

This summer, they assessed kids’ reading needs and provided tailored, structured instruction in phonics to advance each child’s skills.

To give you a sense of the need, imagine a student who entered kindergarten in the fall of 2020, after Covid hit, and had that school year completely disrupted by pandemic-wrought school closure and disruption—on top of preexisting family stress and poverty.

Imagine that child, now a rising third grader, arriving at the summer reading program not knowing the alphabet and unable to form the letter A. Imagine the feeling of defeat hanging over that child after spending three years in school and still understanding so little about our written language.

And then imagine the child’s confidence growing as they’re greeted each day by nurturing staff committed to meeting their needs. Staff with the time, resources, and know-how to help them discern the sounds within words. To help them clap out syllables and break words into sounds.

Who thoughtfully show them the connections between those sounds and letters on paper. Who hand them books well-suited to their skills and give them the gift of reading simple texts.

That’s a win. Not just for those kids, that program, or the generous funders who supported it. It’s a win for our society and collective future.

Like this post? Please share it!

Reading for Our Lives turns 1 today! And bringing this parenting book to the world has been my greatest professional accomplishment so far. It took years of research, interviews, and synthesis to get it into print. The writing itself was a bear, but so was navigating the publishing industry to find a great agent, secure a book deal, and launch—all during a pandemic.

Twelve months into my life as a published author, I’m proud to report that I made 38 speaking appearances and earned more than 100 media features related to the book, including a segment on CBS Mornings and an OpEd in TIME. The book has reached more than 5,000 parents, caregivers, teachers, and literacy advocates and garnered numerous 5-star reviews.

But don’t get me wrong, I’ve had my share of mishaps on my author journey as well. One low light was traveling 1,000 miles to a book signing where the conference bookseller forgot to order my book. Yes, seriously. Astounded, angry, and hurt, I had to muster all of my professionalism and poise to salvage what I could of that disastrous trip. I had to quiet my wounded ego and use my time on site to connect with prospective partners and reconnect with existing ones. Most importantly, I had to remind myself of why I do this work in the first place. My mission is not to sell books—that’s just a means to an end—but to send a message about our national literacy crisis and the responsibility we all share to reverse it.

With or without a book in hand, I want to help people understand the costs of allowing millions of kids to graduate high school without the literacy they need to thrive in the modern, global workforce. I want to connect the dots between low literacy and unemployment, homelessness, chronic health issues, incarceration, and so many other problems we face. I want to spur more parents to own their roles as children’s first teachers, vocabulary builders, and educational advocates.

Someone once said that we overestimate what we can accomplish in one year and underestimate what we can do in ten. I feel that in my bones. So here’s to celebrating year one wins—knowing that there’s much, much more to come!

The question is not whether we can afford to invest in every child; it is whether we can afford not to.

Marian Wright Edelman

Heavy rain once filled our local water supply with so much silt and debris that treatment systems failed. Local authorities and media raised the alarm that residents should boil their water for seven days straight or risk illness. Restaurants shut down. Families bought bottled water by the shelf-full. Hospitals procured truckloads of certified water and switched operating rooms to alternative sterilization methods. Once the boil notice was lifted, we all flushed our pipes, dumped ice machines, and resumed life and work as usual.

The crisis was obvious and urgent. The response clear and immediate. The end apparent.

What’s happening with our nation’s pipeline to reading, if you can call it that, is just as urgent, yet hidden. There is no infrastructure in place to raise a nation of readers, let alone a coordinated response to breakdowns.

Judged by international standards, two disturbing findings characterize U.S. adult literacy in recent decades: basic skills are weak overall (despite relatively high levels of education) and unusually persistent across generations. About one in six U.S. adults have low literacy skills, compared to, for example, one in twenty in Japan. That’s approximately 36 million U.S. adults (roughly equal to the combined populations of New York, Michigan, and Minnesota) who can’t compare and contrast written information, make low-level inferences, or located information within a multipart document. And, worse still, socially disadvantaged parents in the U.S., compared to those in other countries, are more likely to pass on weaker skills to their children.

There is no infrastructure in place to raise a nation of readers.

But here’s the part that all parents must understand: this crisis brews early. Much of the tragedy of low adult literacy has its roots in infancy, when early experiences launch lifelong learning trajectories. During this time, more than a million new neural connections are formed per second, and future brain development rests on the soundness or fragility of those earliest links. In fact, evidence from anatomical, physiological, and gene-expression studies all suggest that basic brain architecture is in place by around two years old and later brain development is mostly about refining the major circuits and networks that are already established. And, critically, it’s caregivers’ nurturing, supportive back-and-forth verbal engagement in a child’s first years that literally stimulates brain function and shapes brain structure.

For too long, as a nation we’ve tested school-aged kids, reported the results, and acted like oversight is a reading achievement delivery system. But literacy doesn’t flow from federal mandates through state assessments and district policy to classroom instruction and students’ brains. Standardized assessments are valuable, but limited, alert systems. Mere indicators, they can sound when our educational system fails to meet certain expectations. But they don’t illuminate the root causes of that failure or tell us what to do about them. Alarms ring; they don’t teach. And often when an alarm rings for too long, we tune them out.

Today, alarms abound. In the U.S., 5-year-olds have “significantly lower” emergent literacy than kids in other countries that have comprehensive early-childhood education and national paid parental leave. In a 2019 reading assessment, only one-third of a nationally representative sample of U.S. fourth- and eighth-grade students scored at a proficient level. Reading scores of the lowest performing 9- and 13-year-olds have dropped since 2012. And—most devastatingly—just 14 percent of U.S. 15-year-olds read well enough to comprehend lengthy texts, handle abstract or counterintuitive concepts, and evaluate content and information sources to separate fact from opinion.

And don’t even get me started on the state of children’s reading interest and enjoyment. National surveys reveal skyrocketing percentages of 13-year-olds who say they “never or hardly ever” read for fun—29 percent in 2020, compared with 8 percent in 1984. The sad truth is this: for the past few decades, the majority of American kids have been shuffled from grade to grade without ever reading well enough. And we’re not talking about children with profound learning or intellectual disabilities. These are capable students whose reading development is hobbled by a devastating mix of untapped opportunity at home and inadequate instruction in schools.

Incredibly, that’s despite the fact that elementary schools devote more time to English, reading, and language arts than anything else—often more than 30 percent of instructional time. Teachers struggle to meet the diverse needs of learners who arrive in their classrooms with little knowledge of the alphabet, the sounds of English, and the relationships between letters and sounds. They have trouble instilling these basics, let alone expanding the oral-language development, vocabulary, and background knowledge that allows kids to decode and comprehend words in print.

We can’t afford to continue pretending that a hodgepodge of reactivity and remediation can get millions of children reading well enough to flourish. We can’t leave whole populations without the skills, knowledge, and community support that underpin full participation in society and expect things to turn out well for them or for us. We all suffer when we don’t muster the collective will, skill, and integrity to ensure that every child learns to read.

To attain the consciousness, solidarity, and equity our society so desperately needs, we must be informed and deliberate in nourishing early literacy. So, too, if we are to engender the level of citizenship, critical thinking, and limitless potential that our children and society deserve. And because the odds of success are set before school begins, we’ve got to start at home.

Parents and early caregivers hold the key. Period. We will never see the promise of mass literacy fulfilled until parents—our children’s first teachers—understand how reading skills develop and how to spur them along.

Premium Fuel

Parents are often said to be kids’ first and best teachers. The “first” part is guaranteed, but the “best” part must be earned. When it comes to literacy, evidence (not intuition) is the best way to judge what works.

Literacy is one of the most-studied topics in academia. There were already more than one hundred thousand studies on how children learn to read in 1999 when Congress convened the National Reading Panel, and the number has continued to climb. A search for the phrase “reading development” in the National Library of Medicine’s biomedical database finds more than 2,500 papers published in 2021 alone. Conferences, publications, and whole careers are devoted to bridging the divide between what research in linguistics, psychology, cognitive science, and education tells us about how reading develops and the practical matter of sparking and accelerating these developments in children.

To attain the consciousness, solidarity, and equity our society so desperately needs, we must be informed and deliberate in nourishing early literacy.

When parents engage with good research and allow it to inform our decisions and behavior, we benefit from the wisdom of evidence and analysis that’s far more revealing than our individual experience or perspective alone. Recent discoveries in neuroscience, molecular biology, and epigenetics alongside years of behavioral and social sciences insights can also boost our empathy by giving us deeper insight into the child’s environment and experience. I know I always feel better about my decisions as a mom when they marry responsiveness with effectiveness. I want to do not only what feels right, but also what works.

Routine Maintenance

Becoming literate is considerable work for a child’s growing brain, but nurturing it doesn’t have to be. Beginning in infancy, parents can foster literacy with warmth, responsiveness, dialogue, and turn-taking. Over time these practices can become core habits and make a lasting impact. These are everyday strategies to help you find the perspective and build the muscle needed to relate to your children with intention, consistency, and generosity over the long haul.

The fact is, once parents know what the research says about what kids need (and when), there’s a practical matter of doing those things day in and day out… for years. For that, we need parent-tested and -approved techniques that are easy to fit into busy lives. Putting the time and energy into establishing strong practices early on can rev up lifelong benefits and prevent costly breakdowns.

Roadside Assistance

A lot of parenting media treats families as islands. Read this and teach that, the books advise, and your child will learn. But in reality, reading develops within a dynamic web of relationships and experiences.

Parents need ongoing support from community members, including friends, family, neighbors, teachers, librarians, and others, to keep their kids on track. There’s often also a role for the just-in-time intervention of specialists, from speech and hearing therapists to learning and reading experts, depending on a child’s particular needs. This is the equivalent of roadside assistance.

But we’d be foolish to take a back seat, given the indisputable evidence of our power to launch a child’s literacy. Every child deserves full literacy to thrive, and instilling the strongest possible base prior to school gives a child a real shot at gaining the skills and knowledge they‘ll need long term.

When I was growing up, my dad always told me to front-load my effort. He said, “Work as hard as you can to learn as much as you can as fast as you can.” That way, when inevitable distractions and unforeseen circumstances arrived, I’d have some wiggle room. Starting strong creates a chance at recovering from setbacks. So it goes with your child’s literacy: you will never find a better time than now to launch a reader.

Edited and reprinted with permission from Reading for Our Lives by Maya Payne Smart, published by AVERY, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Copyright © 2022 by Maya Payne Smart.

Enjoyed this excerpt? Get the book!

It’s the most wonderful (and busy) time of the year. And I’ve got you covered with a set of printable activities that will give you easy, fun ways to bond with your little ones over seasonal fun—and even build some learning into your festivities!

These six sweet activities are specifically designed to make nurturing and teaching reading a natural part of your holiday plans. There are activities with Christmas, Kwanzaa, Hanukkah, and New Year’s themes.

They will help you use everyday activities like Elf on the Shelf, baking & cooking, and arts & crafts to incorporate learning in a fun & joyful way!

Download the Holiday Play & Learn Activity Kit and get 6 printables that will help you:

⛄ Use Elf on the Shelf to encourage writing & imagination

⛄ Bake memories with three easy DIY recipes that blend family fun & reading practice

⛄ Have your budding reader color in printable bookmarks to tuck into favorite books

⛄ Reflect and connect with a New Year’s family memory activity

Inside you’ll find:

Elf Pen Pal Writing Paper

The Elf on the Shelf is incredibly popular, and for lots of good reasons—it can be really fun and contributes to the magical feeling and anticipation of Christmas.

But it can also have a downside. The elf is nominally about spying on kids’ behavior and reporting to Santa on whether it’s gift-worthy. This concept could reinforce a materialistic view of the holiday and cause a child’s relationship with the elf to tilt away from Christmas values such as charity, togetherness, and love.

But never fear! You can use your Elf on the Shelf for social-emotional learning, family bonding, and literacy practice, instead—by turning it into a Christmas pen pal for your kids. Get tips in the kit, plus adorable elf-themed writing paper to use.

Read with Me Holiday Recipes for Kids

Maya Smart Read with Me Recipes are printable recipes that are easy for kids to make and read. Simple words and short sentences in a clear font set your little one up for reading success.

The idea is to make it quick and fun for you to mix reading and writing into everyday life with your child. This kind of “everyday literacy” is key to raising thriving readers.

You can read these recipes aloud to pre-readers or encourage beginning readers to sound it out themselves. Use the recipes with young kids of any level, from tots who don’t recognize any letters of the alphabet to early readers.

Download the activities to get three printable holiday recipes for kids: DIY christmas ornaments, latke potato pancakes, and yogurt bark—plus tips on how to use them to foster learning along with fun.

Color-Your-Own DIY Holiday Bookmarks

DIY bookmarks are a fun and easy activity, stocking stuffer, or DIY gift. The kit includes three sets of color-your-own holiday bookmarks, with Christmas, Hanukkah, and Kwanzaa themes.

Activity: Making a personalized bookmark is a fun way to encourage reading—even when it’s just your little one turning the pages to look at the pictures. This “pre-reading” builds the reading habit and book love.

Stocking stuffer: The undecorated bookmarks can make a fun and free last-minute mini-gift for kids. You can even laminate the undecorated bookmarks to create reusable craft that your child can color again and again with dry-erase markers.

DIY Gift: Kids love giving gifts as well as receiving! Your child can color and decorate these cute bookmarks as a homemade gift for their loved ones.

New Year’s Coloring Worksheet

In the same way that the key to a great morning is a good night’s sleep, a little-known trick to start your new year off right is to spend some quality time reviewing the year before.

The printable activities include a cute worksheet and coloring page for your child to fill out with highlights and reflections about the past year.

First, help your child brainstorm what they want to include in the sheet. Back-and-forth conversation with you is key to building their brain in ways that facilitate reading later!

Then write their ideas down for them on the worksheet (or help them write a few words on their own if they’re able). They can also draw pictures to illustrate their ideas.

Know someone who might like these play & learn holiday activities? Share this post!

Children grow and develop at incredible rates between from birth to three years old, and parents have a front-row view of it all. So it bodes well for kids’ long-term literacy when caregivers use our special vantage point to monitor developmental milestones and proactively seek support when we suspect developmental delays.

Yet, many parents don’t know that they can access federal funds for early-intervention services, even without a referral from a pediatrician. Funds are available for children experiencing needs in areas including gross and fine motor skills, speech and language, and social or emotional areas.

That’s why I reached out to Ann Becker and Shannah Seyfert of Penfield Children’s Center, which administers Birth to Three programming in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. I asked them to explain why early intervention matters, who parents can talk to if they’re concerned about their child’s development, and what kinds of support services children can receive.

Watch the video for tips about how to tell if your child has a developmental delay and what to do if you suspect an issue. Then spread the word about early-intervention services in your neck of the woods. There are federal funds available in every state, through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act Part C, although there are some variations in the program specifics.

Here’s a breakdown of key topics from my chat with Ann and Shannah:

- Why parents should pay attention to developmental milestones issued by the CDC and other reputable organizations.

- Red flags that parents should attend to when it comes to early-childhood development.

- The importance of honoring your intuition as a parent, documenting your observations, following up on concerns right away, and seeking outside support and assessments when you’re worried.

- How healthy relationships are the foundation of a child’s brain development and skills.

- The importance of prenatal care and well-child checks at the pediatrician’s office.

- How services are delivered through a primary coach and an extended network of specialists, such as an occupational therapist, a physical therapist, a speech therapist, an educator, or a social worker, depending on their needs.

- How anyone—parents, physician’s offices, and child care centers—can refer a child to get early-intervention services on the county website.

- What to expect if your child is referred for assessment, from the initial referral to an interview to an assessment to getting a family service plan if your child qualifies.

- How children transition out of the Birth to Three program, and what kind of ongoing support is available through the public schools’ early-childhood system.

My chat with Penfield Children’s Center’s Birth to Three program was so informative and encouraging. I want all parents to see how easy it is to raise your hand and express any concerns you have about your child’s development. Your early invention can make a lifelong difference for your little one, so don’t hesitate to follow your intuition when it comes to seeking assessments and support for your child.

Links and resources mentioned in this conversation:

Like this post? Share it!

If you’re raising a baby or small child, you’ve probably felt pangs of parental guilt coming from some surprising places. And one unfortunate trigger can be the subject of reading to your kids. Some parents beat themselves up for not doing it, while others worry that they don’t read often enough or long enough. (And, let’s face it, when does anything really feel like “enough” for our little charges?) Still others fret if their toddler doesn’t seem to listen, or squirms or wanders off during story time. Many worry that their young ones don’t seem that “into” books—and that it’s their fault.

But pediatrician and reading advocate Dr. Dipesh Navsaria has a reassuring message for parents. It turns out that what matters is interacting with kids and exposing them to books, not fulfilling some unattainable ideal. I’ll share the doctor’s key advice below, but first, a little more about this medical-doctor-slash-reading-advocate.

While studying medicine at the University of Illinois, he stumbled upon a children’s-book research library on campus. Inspired, he followed his curiosity about young people’s literature all the way to pursuing a master’s degree in library science in the middle of his med-school career. Now he’s a pediatrics professor at the University of Wisconsin and helps parents foster little ones’ language and literacy skills as the founding medical director of Reach Out and Read Wisconsin.

The nonprofit serves 170,000 children and their families via doctors’ offices in 56 counties across the state. Participating pediatricians deliver books to children (more than 250,000 to date!), but even more critical is the support they provide to parents as kids’ first and best teachers. They help ensure that shared reading is an everyday part of young children’s lives and that parents feel capable and confident about reading with their kids, Navsaria says.

Watch my interview with Dr. Navsaria, or read the highlights below, to learn how shared reading contributes to kids’ flourishing—and why read-aloud time is valuable even when it’s squirmy, messy, and short. Plus, you’ll discover how to make the most of pediatrician’s visits and how to refer your child for early-intervention services if you think their development is lagging.

Here are key tips from our conversation:

Keep Reading Time Flexible and Conversational

Giving a child a book during a checkup visit gives doctors a powerful window into a little one’s wellbeing, Navsaria shared—much more quickly and viscerally than rote answers to checklist questions.

“The toddler who takes that book and toddles over to their parent and holds it out in that read-to-me gesture, they’ve told me a ton,” Navsaria says. “Not only have they told me about the developmental domains (fine motor, gross motor, maybe some language, whatever), they’re also telling me something really important … [about] relational health, the health of relationships.”

So what does that mean for you as a parent? It highlights that when you read with your child, you’re giving them so much more than words on the page. You’re giving them opportunities to explore the physical book itself, to hear the sounds of English (or whatever language you read in), to discover more of the world and the words that describe it, and to engage with an adult who loves them.

And, wonderfully, those benefits of reading together exist whether your child is sitting still, gazing at the page or not. This message is particularly important for parents of toddlers, who often express concern that their children are wriggly and “don’t like” books. In reality, Navsaria said, it’s usually just toddlers being toddlers, while parents read at them instead of with them.

Instead of diligently narrating the text and hoping to capture their attention, Navsaria advises, “pull them into your lap, give them the book, let them turn the page, let them go backwards in the book, pick up random pages, talk about the pictures, ask questions about pictures.”

“It doesn’t matter if you never read the story,” he explains. “I’m not going to ask you to write an essay on it. … When [parents] can deviate from that script and instead just have fun interacting, that works really well with a squirmy toddler, and then when they’re three or four and their attention span is much better, they’re more likely to listen to the book.”

Permission granted to be flexible—and conversational—when reading with littles.

Elevate Doctor Visits from Check-Ups to Level-Ups

Often parents head into well-child visits at the pediatrician’s office with low to no expectations. They think the child will get weighed and measured and maybe given an immunization. But there’s an opportunity to use those brief engagements to level up your knowledge as a parent, too.

While doctors have a list of specific items they want to cover during a visit, they also expect and appreciate when parents ask questions or bring up concerns. In fact, Dr. Navsaria says that when he trains pediatricians, he advises that the very first question they ask parents should be, “What questions or concerns do you have for me?” The opening invites the parent into discussion and puts the family (not a visit checklist) at the center of the appointment.

The leading national pediatrics guidelines, like the Bright Futures and Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (both on the bookshelf behind Navsaria during our chat), endorse this kind of engagement with families, he says. The guidance encourages doctors to talk to parents about learning, behavior, and development. “Those works tell us about how important it is that we engage with families and discuss all these things and not just things that people might view as traditionally medical,” he says.

If your checkups feel, instead, like you’re being asked a bunch of rapid-fire questions and that’s it, he advises looking for another healthcare provider.

Trust Your Gut If You Think Your Child is Missing Milestones

If you’ve ever worried that your child was falling behind other kids their age in speech, movement, or some other area, let your pediatrician know. “Tell us what it is you’re seeing,” Navsaria advises. “You don’t need to use the right terminology. Our job is to help piece that together.”

“If a parent comes in and says, ‘I’m concerned about my child’s development,’ that’s almost automatically a reason to refer,” he explains. “Parents spend untold hours around their child. I get to spend a very short amount of time. I have the benefit of having seen thousands of children …. But any individual child, I don’t have a whole lot of time with them.”

Navsaria also explained that if a parent is concerned about their child’s developmental progress and feels they’re not getting proper attention or reassurance from their doctor, they can usually apply directly to state early-intervention services. (See my interview about Birth to Three early intervention services and developmental delays here.)

So, as you can see, pediatricians can be valuable resources and sounding boards for parents on the raise-a-reader journey. Take this expert’s advice and pair your own observations with your pediatrician’s professional experience to navigate your little one’s next steps in language, literacy, and learning. Staying flexible, asking questions, and trusting your instincts go a long way toward your child’s success.

Reach Out & Read Podcast

To hear more engaging conversations with experts in childhood health and literacy, check out the Reach Out & Read Podcast.

Listen NowAbout a year ago, on my daughter’s birthday, I received an email from Linda Mitchell, the executive director of Metro East Literacy Project in East Saint Louis. I’d never met her before, but she wrote a heartwarming note that “we’re kindred spirits when it comes to literacy.” It was exactly the kind of reader mail that every author hopes to receive—confirmation that people have read your work, engaged with its ideas, and felt strongly enough about it to reach out.

Linda had subscribed to my weekly newsletter and read my OpEd in TIME. That day in her email she shared a bit about her own literacy advocacy and wrote “Thanks for doing all the wonderful work you do to help families live better lives through literacy. I want to be like you when I grow up. :).”

Today, I’m returning the compliment by going on record as a fan of Linda’s grassroots work to empower families with literacy. She has been instrumental in building the confidence and home libraries of parents in her community. Linda spent years as a traditional classroom teacher in grades one through twelve, then worked as a parent educator with the Parents As Teachers program. These experiences led her to an epiphany: “Literacy begins at home. That’s the powerhouse.”

So she began delivering books to families in underserved neighborhoods and founded the Metro East Literacy Project. Nowadays, people call her The Book Lady. Notable Human Films produced a mini-documentary about Linda that powerfully communicates her deep dedication to family literacy, inspired by her grandmother’s inability to read.

In the documentary, Linda explains, “It just makes me mad when I think about my grandmother, who was denied the right to read, wasn’t taught to read and write, and before her, all the other enslaved people who were denied that. And there’s a reason for that, because reading is so powerful.”

“I credit everything in my life with having that skill,” she says. “I can teach myself. I’m teaching myself languages. I’m teaching myself anything because I can decipher those words on a page I can comprehend. And to think that there are people who are not able to do that and navigate their lives, and they suffer. They suffer because of it. I feel like it’s my divine assignment. And so no matter how steep the hill is, I’ve got to keep climbing, because there’s somebody, some family out there who’s going to be free, their literacy is going to be their liberation. It’s going to take them higher, and that’s what I believe.”

Fostering literacy for all takes all of us doing what we can to make a difference in our spheres of influence. May Linda’s work inspire you to champion reading in your home and beyond.

Like this post? Share it!

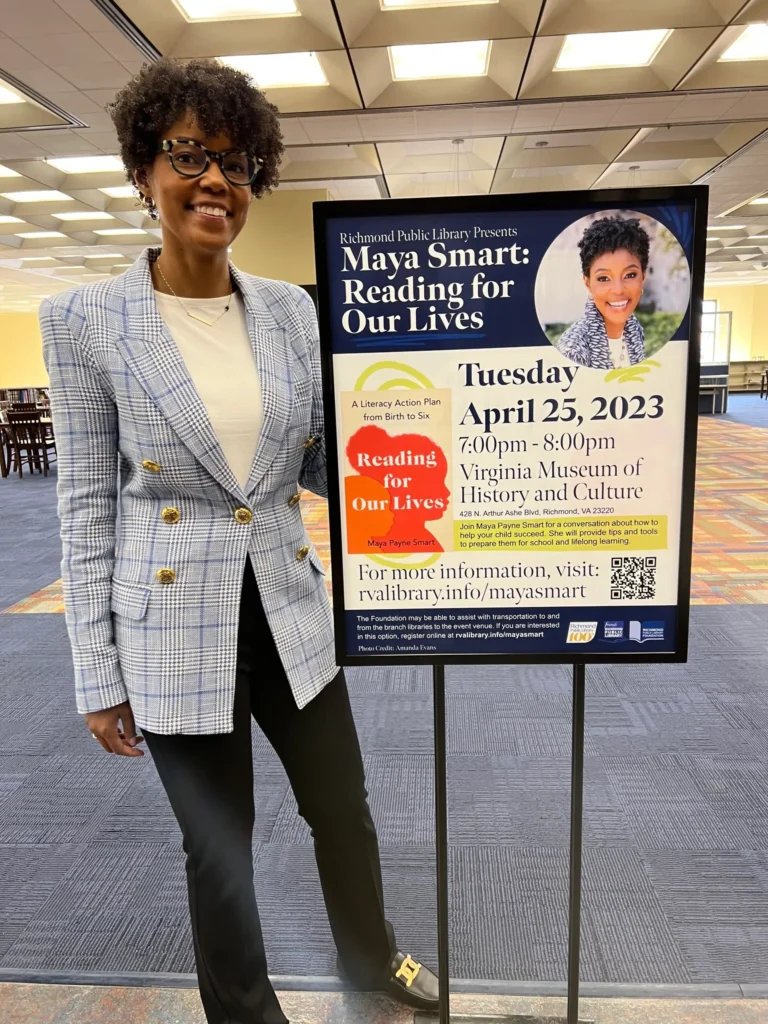

Exciting times ahead! As December races to a close, we’re just a heartbeat away from the January debut of my very first digital course for parents. But before we get into 2024, let’s reflect on the whirlwind that was 2023.

The highlights: I had the privilege of connecting with audiences at more than 50+ events and media appearances. Some were in-person—from bustling auditoriums in Santa Barbara, California, and Richmond, Virginia, to a family literacy night in a school cafeteria and a parent event in a children’s museum’s play grocery store here in Milwaukee. Others were virtual, from interviews with outlets in Portland, Oregon, and Greenville, South Carolina, to more intimate online gatherings of librarians from Maryland and Kansas.

No matter where I found myself, the core message remained the same: Literacy is for everyone and fostered by everyone. I love sharing the nuts and bolts of reading development—the power of everyday conversation and teachable moments with kids—because that’s how change happens, through one person talking, reading, playing with, and nurturing another.

What I know for sure is that we will never attain the levels of literacy we need for our society to thrive until we fully engage parents in the earliest years of kids’ lives. That’s when early experiences and language (or their lack) set a lifelong trajectory for educational success (or struggle). Let’s keep the conversation going!