Tara Mohr is on a mission to help women speak up and influence the world for the better. She says her lifelong calling is ”to recognize where women’s voices are missing and do what I can, in my corner of the world, to help bring them in.”

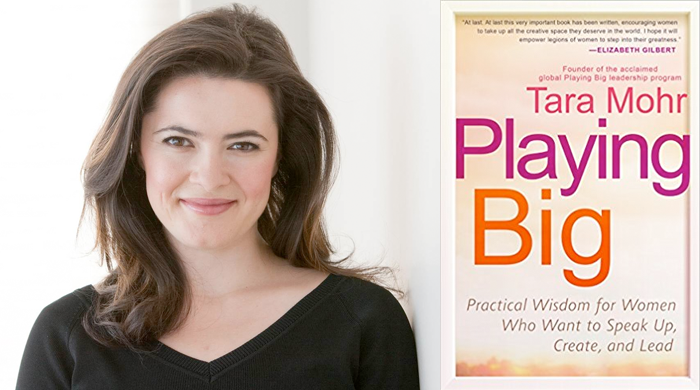

As a child, Mohr advocated for an English curriculum that featured more women authors and female protagonists. Today, she’s running a global leadership program and sharing its central tenets with a wider audience through her book, “Playing Big.”

Heartening and pragmatic, the book reads as if Mohr is giving an extended pep talk to an imagined reader who has great promise but craves support. “You are that talented woman who doesn’t see how talented she is,” Mohr declares in the opening pages. “You are that fabulous, we-wish-she-was-speaking-up-more woman.”

The message is a variant of the encouragement she’s given to thousands of women through her coaching practice. The book is a distillation of the best material generated in that laboratory–those exercises and advice that women found to be most helpful in creating the lives and careers they sought.

Mohr’s Inner Critic 101 Training and toolkit of 15 ways to quiet fears are worth the cover price alone. Collectively, the many lists, steps and journal prompts fill the void left by other manifestos that tell women what to do without explaining the mechanics of how to do it. For every grand declaration (“One of the most important mental shifts a woman can make to support her playing big is to start thinking of criticism as part and parcel of doing important work”), Mohr offers multiple tips and tools to make it concrete.

What the book lacks, though, is much of the fire and heart that makes manifestos persuasive and memorable. You’ve got to bring your own motivation to this text because it lacks the spunk of Lisa Bloom calling out women for letting celebrity culture distract us from social ills, or the sharpness of Anne-Marie Slaughter listing the 1,001 ways women are thwarted in efforts to advance. Mohr’s tone is decidedly pleasant (not accusatory), in keeping with her stated belief that “tender friendship” is more potent than criticism. While I appreciate how her writing reflects her gentle ethos, I must admit that saltier approaches make for livelier reading.

In fairness, the subtitle is “practical wisdom for women who want to speak up, create, and lead.” It wasn’t designed to awaken latent aspirations. It’s for the woman who already wants to lean in and doesn’t know how.

That’s not to say the book is just for corporate climbers. The text’s frequent references to women of diverse ages, professions, circumstances and aspirations suggests that the advice is widely applicable and effective. Mohr references women from many walks of life who have practiced Playing Big. For example, there’s a Silicon Valley sales director who wants to launch a new line of business, a researcher emboldened to approach a rival lab about collaborating, a social worker who wants to transition into advocacy, and a literacy specialist who wants to open a camp. The women could not be more different, but they all benefitted from Mohr’s core set of tools for quieting criticism, communicating powerfully and taking productive action.

Mohr’s focus on inner work, versus the details of salary negotiations or other tactics with narrow applications, assures the book’s appeal to a wide range of women. And unlike many women’s empowerment books, these practices are not meant to be deployed in a grab for more power and prestige. Mohr’s stated goal is to help women move past self-doubt to create whatever’s meaningful for them. It could be launching a business or winning a promotion, but it could also be leading a community initiative or writing an op-ed for the paper. As Mohr puts it: “This is the very heart of playing bigger: having the vision of a more authentic, fully expressed, free-from-fear you and growing more and more into her, being pulled by this resonant vision rather than pushing to achieve [external] markers of success.”

One of the most compelling portions of the book describes a conversation she had with her childhood dance instructor, who told her that American women were liberated but not empowered, because they lacked imagination. Mohr understood that to mean that women weren’t fully claiming their freedoms because they lacked a “specific, vibrant, compelling vision” for doing so. In short, they were stuck recreating the status quo of playing small because it was modeled all around them and they hadn’t cultivated the inner capacity to create new, better alternatives. This is a compelling idea that bridges the personal and social dimensions of Playing Big. When more women do it, more will see it and do it too.

At several points in the book, Mohr tries to raise the stakes of women playing big beyond the realm of individual happiness to evoke global import. (“In the minds of women around the globe lie the seeds of the solutions to climate change, poverty, violence, corporate corruption.”) She writes that women who speak up are “naturally” change agents and revolutionaries because today’s public, professional and political lives are “not yet reflective of women’s voices or women’s ways of thinking, doing and working.” This is too much of a leap for me. Sarah Palin speaks up, but what she says is ignorant and divisive. The content and intent of speech matters more than the mere fact of it. The elevation of women’s voices is necessary but not sufficient for positive social change.

Although Mohr’s rallying cry fell flat for me, the book’s practical advice remains valuable. It succeeds in equipping ambitious women, if not rousing them.

If this review resonates with you, I bet you’ll enjoy my newsletter. I regularly send bookish news and notes out to more than 1,000 readers. Sign up here.