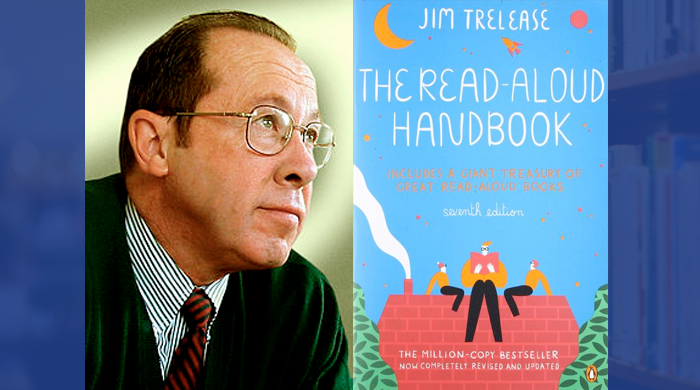

Jim Trelease’s “The Read-Aloud Handbook” is so much more than its title suggests. Sure, it explains what to look for in storytime selections (no dialect, obscenities or weak plots, for starters). But its real strength is a smart and compelling explanation of why parents should read to their children early and often, from infancy onward.

Raising a lifelong reader is the single-best investment a parent can make, Trelease insists. Enthusiasm for reading ensures the range of knowledge and learning capacity that kids need to face challenges in school and beyond.

Importantly, Trelease urges parents to provide reading inspiration, not reading instruction. In his view, parents don’t have to learn the ins and outs of phonics and phonemic awareness or even do alphabet drills in order to lay the groundwork for their children’s academic and life success. Quite the opposite, Trelease posits that parents’ first and most important work is merely introducing their children to the world of print in ways that make them want to read. That is, cuddling up daily and enthusiastically reading great books. No specialized training or fancy curriculum required.

In fact, the book argues that much of what kids need to learn about reading from their parents is more “caught than taught.” That is, it comes through consistent exposure, not explicit instruction. Our efforts during the thousands of hours before children enter school — and outside of school in later years — set the tone for their lives. A steady diet of read-aloud time at home can spark sufficient reading inspiration to render much of the school-time remediation we call reading instruction unnecessary.

“Contrary to the current screed that blames teachers for just about everything wrong in schooling, research shows that the seeds of reading and school success (or failure) are sown in the home, long before the child ever arrives at school,” he writes.

As proof, he offers academic research and anecdotal accounts of parents who inspired their children to read through daily reading and role modeling. Kids who are read to, encouraged to discuss books, see a wide variety of printed material at home, see their parents reading, and have ready access to pencils and paper fare better than their peers raised without a literacy emphasis, he says.

Now in its seventh edition, the book has grown in depth and includes stories of people who have put Trelease’s ideas to work and experienced great results. Stories like that of Erin Hassett, whose parent started reading to her on Day One in 1988 (and documenting the books and her reactions), enrich the book. These real-life examples remind us that raising a reader is a years-long process and give parents a vision of the results they may attain with dedicated daily reading.

To nudge readers from contemplation to action, he devotes the latter half of the book to a treasury of thoughtfully vetted books to read aloud to children from infancy through high school. Authoritative, but not definitive, it’s meant to jumpstart reading aloud by pointing to some appropriate and accessible titles, including picture books, novels, poetry and folk tales. Each entry includes a recommended listening level to give you a sense of the text’s difficulty and appropriateness for your child.

While much of the book’s content was not new to me, I closed the book with a sharpened focus on what I should do with the information as both a parent and a citizen. My commitment to daily reading with my daughter was strengthened, as was my drive to advocate for libraries and community-based family literacy programs. “The Read-Aloud Handbook” offers persuasive arguments that reading starts at home and a welcome wake-up call for us all to spread the word.

If this review resonates with you, I bet you’ll enjoy my newsletter. I regularly send bookish news and notes out to more than 1,000 readers. Sign up here.