I have walked by Barkley Hendricks’s painting “Sisters (Susan and Toni)” in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts more than once. But I never paused long enough to fully consider it … until today.

Its subjects always struck me as cool—fashionable and aloof, but not much more than that. They are two black women, set against a matte black background, in not-quite-life-sized proportions, with only the glimmer of jewelry and some pops of blue and green to draw notice. I saw the women, but I didn’t appreciate their painter’s artistry. That’s the trick of photorealism: the beauty’s in the details.

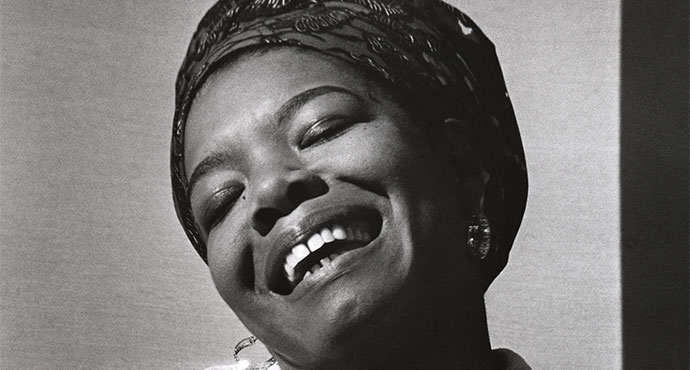

This evening, I saw the acrylic and oil canvas anew as I read Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise” to the painting, museum-goers and the curator who acquired it. I presented Angelou’s work (published in ‘78 a year after “Sisters” was painted) in the gallery as a part of the African American National Read-In. The 25-year-old event is led by the Black Caucus of the National Council of Teachers of English and aims to engage hundreds of thousands of people in the simultaneous celebration of black writers.

The art museum read-in setting was a stroke of genius by the event’s organizers that allowed the visual and literary arts to amplify one another’s impact. My reading spot was just one of eight they dispersed around the museum. Participants from schools, churches and community groups read black writers’ words in front of pieces ranging from Statue of Senkamanisken, King of Kush from 643-623 B.C. to a Richmond Barthé plaster bust of Paul Laurence Dunbar from 1928.

I spent an hour intoning Angelou’s words for several small groups who passed through the gallery, but I received an education in Hendricks’s painting, too. He was an oddity at a time when abstraction, Pop, Minimalism, Conceptual Art and Postminimalism reigned. He labored steadily and meticulously in the service of his own vision, a 17th Century-inspired traditional realism made fresh by use of everyday black people as subjects.

After several recitations of the poem in the presence of the canvas, the two are forever linked in my mind. Angelou must have been writing about Susan and Toni, and the millions of sisters like them, when she penned “Still I Rise.” For their postures and steady gaze, wrought through layer upon layer of translucent oil glazing, illustrate just the resilient ascendance the poet describes. Her words give pitch-perfect voice to the cool charge in their brown eyes: Does my sassiness/haughtiness/sexiness make you uncomfortable? Little matter. I rise.

Provocative and unflinching, “Sisters” and “Still I Rise” represent mirror images of black womanhood in all its arresting beauty. I was honored to spend an evening in their presence.

Still I Rise

by Maya Angelou

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may tread me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

‘Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I’ll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops.

Weakened by my soulful cries.

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don’t you take it awful hard

‘Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own back yard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I’ve got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.