When people ask what my favorite book is, I always respond with Jacqueline Woodson’s 2012 picture book Each Kindness. But truth be told, everything she writes, from picture book to poetry to novel, is wonderful. Each new work prompts me to consider central questions of who we are, why we are, and how we can grow for the better. And, because I adore her writing and her advocacy for reading, I interview her every chance I get.

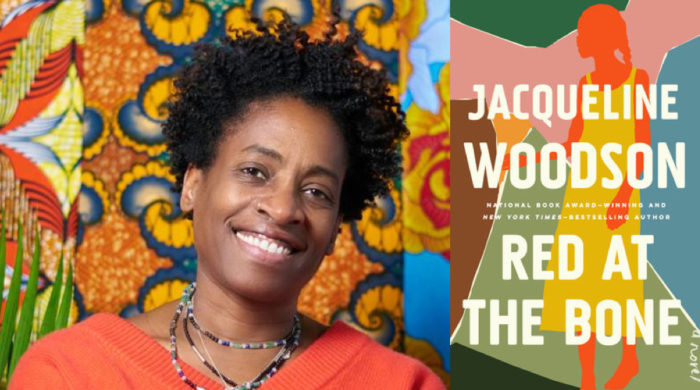

Here’s an excerpt from our October conversation about her novel Red at the Bone for BookPeople in Austin. We discussed how to write memorably, build authorial confidence, and address different audiences. Her words inspire me to write more, and more bravely.

Your writing has a certain velocity to it. In Red at the Bone, you jump right into the story and move from moment to moment. You go back and forth in time, incorporating characters who are in the moment but also in memories. What gives you the confidence to leave out the adjectives, strict chronology, and detailed descriptions?

I think poetry gives me a lot of confidence—reading poetry and seeing the chances that poets take with their writing. Having written 31 books gives me a lot of confidence, knowing that I can kind of take these chances in my writing. Also, wanting to create a new narrative and not tell the same old story the same old way again [gives me confidence], mainly because I get bored. If I’m writing and I’m feeling bored writing, I know that writing is boring.

One thing about time is no one ever comes into someone’s life at the beginning of it. It’s the beginning of a relationship, but it’s not the beginning of that life. When I was thinking about the whole intersectionality of the characters, I had to look at the beginnings and the endings and the middles of their lives and write accordingly. And so I wasn’t going to write Chapter One, this happened, Chapter Two, Chapter Three. I had to go back and forth in time to tell this story.

At the start of the book, when Melody is being presented to society, she has chosen a questionable version of Prince’s “Darling Nikki” as the music to accompany her grand entrance. The original song is so raw and percussive. There’s a lot of screaming and grunting and all this stuff going on. But on this occasion, it’s a wordless cello, harmonica, and bassoon rendition. You can just imagine that remix of the ritual. So tell us a bit about that music choice and that character’s debut.

So, we’re in 21st century Brooklyn, and here is this stuff from the early 1900’s that they’re asking her to pay homage to. And she’s a teenager. Having a teenager of my own, I know they are constantly pushing against those boundaries. So I asked myself, how would this character push against this boundary? And, of course, “Darling Nikki.” I knew a girl named Nikki, I guess you could say she was a sex fiend, I met her at a hotel lobby, masturbating with a magazine, are the opening lyrics of this song.

She has this huge fight with her mother about that song. It is about her having agency, her saying, yes, I am part of this narrative, but I am also my own person and I’m going to do stuff differently, and Prince just worked.

The book opens with Melody turning 16. Other scenes reflect on her parents’ teen years, yet Red at the Bone was written for adult readers. How do you decide, as a writer, this one is for adult readers, this one is for young readers?

One of the things with young adult literature is the character tends to stay the same age, and it’s from their point of view. [In Red at the Bone,] some of the points of view are adults and some of them young adults. I don’t curse in my young adult books and my children’s books and I curse a lot in this book. There’s not any sex in my young adult or children’s books and there’s that in this. That’s not to say that there aren’t young adult or children’s books that have sex and cursing in them, it’s just my personal choice not to do that.

One other thing that feels very adult to me is the way I move through time. I do think a younger reader would have a hard time following that because it comes from a place of experience that I think happens when we’re a little bit older. We know that life is tangential, right? We go off on tangents and then we will return to a place. But [when writing] for young people, I tend toward a more straight narrative.

Do you approach writing a picture book, a middle grade, a young adult, an adult project differently?

Yeah. Whenever I do a picture book, it’s like I’m writing a poem. I’m very intentional about the line breaks. Look at something like The Other Side:

That summer the fence that stretched through our town seem bigger. Line break. We lived in the yellow house on one side of it. Line break. White people lived on the other. Line break. Momma said don’t climb over that fence when you play. Line break. She said it wasn’t safe.

So each line offers a picture into the world that moves the reader along the page. And then by the time you get to “She said it was a mistake,” the reader wants to turn the page to find out what was a mistake, right? You want to constantly have the reader turning the page. Really young kids don’t have a long attention span and if you don’t deliver with that first line, you’ve lost them. You know, they’re done, they’re like, “This is a wrap—where is the next book that’s going to entertain me?” And I have a deep respect for that.

When I’m writing for middle graders, it’s much more immediate. When you look at something like Harbor Me, I’m writing in the face and in the conversation and in the world. With young adults, it’s a bigger canvas and they can assume more, they’re kind of meeting me from their experience a little more, so I can imply more.

And then, of course, when you get to adults, the reader is bringing a lot more of their own experience to the narrative. So the tone is different, too.

And are you able to work in all the different spaces simultaneously?

Yeah, I just finished a picture book and I’m working on a middle grade book. When I was writing Red as a Bone, I was also working on Harbor Me and The Day You Begin, so I’m all over the place.

As the Library of Congress’s 2018-2019 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, you had a slogan: Reading = Hope x Change. Do you have the same sense of mission for your books?

I do believe that when we read it gives us hope. I learned that directly through young people. You can write a book that doesn’t necessarily have a happy ending, but as long as there’s hope somewhere in the book, you’ve done your work.

I feel like I’ve also brought that to my adult novels. That hope has to be there. If we didn’t have it, we wouldn’t get out of bed in the morning. And I do think that when we read a book that we really love and deeply engage in, it changes us. We’re a different person when we close that book than when we opened it. We’ve gotten into a different world. We learned something we didn’t know about people we didn’t know. Our empathy has grown.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.