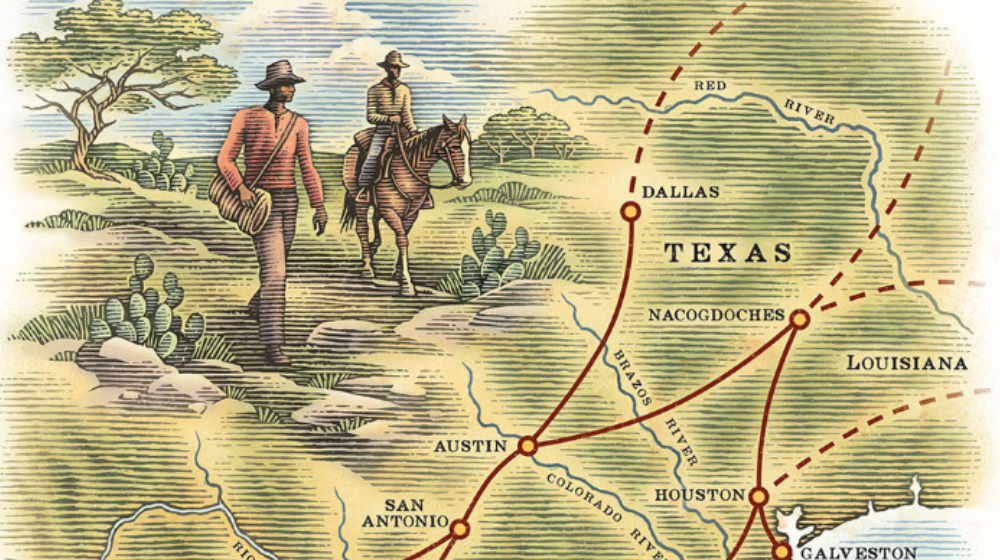

Without a coordinated network of support, fugitives fleeing slavery faced a harrowing journey.

By Maya Payne Smart

Hundreds of Underground Railroad historical markers span the United States, conjuring images of covert escape routes, shrewd conductors, and clandestine connections. Such high-stakes adventure tales grip the American imagination, inspiring books and movies about antebellum liberty pursued and denied, borders permeated and fortified, identities shed and remade.

But Texas is seldom mentioned in this sweeping narrative of Black pursuits of freedom. The state’s landscape is bare of monuments to resistance and flight, of the names or narratives of enslaved people who liberated themselves or died trying. When Texans think of emancipation, Juneteenth is more likely to come to mind—the holiday commemorating the 1865 date when Union soldiers landed in Galveston and announced emancipation.

Yet, “the story of freedom in Texas is bigger than Juneteenth, and it started well before June 19, 1865,” says Daina Ramey Berry, chair of the University of Texas at Austin History Department and author of The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation. “It’s in the stories of self-liberated enslaved people who were finding ways to get to Mexico, finding ways to get on boats and get to the Caribbean, finding ways to escape and go farther west.”

Historians are still unearthing tragic and triumphant tales of Texas freedom seekers, but it’s clear the Underground Railroad’s reputation for coordinated networks of abolitionists hiding people in barns doesn’t square with the historical reality in Texas. Racing south across unforgiving country, runaways—often armed and on horseback—faced daunting odds in a gauntlet of wilderness, slave hunters, and lawmen. “We need to figure out what the Texas story of the Underground Railroad was and maybe come up with a new term or a new label to describe the movement for freedom in the Lone Star State,” Berry says.

Mexico outlawed slavery in 1829, making it an obvious destination for freedom seekers from Texas and other states, such as Louisiana and Mississippi. But getting there required navigating slave states without the support or protection that was sometimes available in free states.

Nineteenth-century Texas wasn’t home to abolitionist societies eager to help runaways. And, considering the number of free Black people in pre-Civil War Texas never rose above a few hundred, hiding in plain sight wasn’t possible. As a result, assistance networks for fugitives in Texas tended to be loose and unstable, says Thomas Mareite, a French historian at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

In his studies of how enslaved people in the U.S. sought refuge, Mareite has found that most of the assistance offered to runaways—directions, guidance, supplies, or shelter—came from fellow Black people, sympathetic Mexican laborers, and to a lesser extent, German settlers who opposed slavery. Though technically “free,” Mexican migrant workers often labored with slaves and developed personal relationships with them. Their empathy, experience crossing the border, and Spanish made them able guides and intermediaries for runaways seeking to abscond south. Slaveholders were sometimes dismayed by the help Mexican laborers offered Black escapees, to the point that some Texas towns expelled Mexican workers from their jurisdictions altogether. Others opted to make examples of those who helped escapees by publicly whipping or hanging them.

Mareite mined municipal, county, and state archives; military and court records; and newspaper articles and “runaway slave” ads to uncover freedom seekers’ stories. But historical records are scarce: Runaways and their supporters carefully covered their tracks in the face of violence and persecution. “People were speaking out against slavery in Texas before the Civil War, but not that many people,” Mareite explains. “Those who did faced a lot of risks—mobs, lynching, brutal punishment.”

Ultimately, enslaved people relied on their own hard-won knowledge, skills, and provisions to pursue freedom. The Texas Runaway Slave Project, a database of historical records at Stephen F. Austin State University, has documented more than 2,500 escapees in Texas. Horseback skills, in particular, aided in the dangerous trek to the Rio Grande. Many enslaved men were skilled with horses from their experience driving wagons, plowing, and running horse-powered cotton gins. In fact, Texas runaways were 10 times more likely than those in Louisiana to take off on horseback, and 16 times more likely than enslaved people in Mississippi, according to the database’s project manager, Kyle Ainsworth, who penned an article on the topic for The Journal of Southern History.

Still, crossing the Nueces Strip—a lawless span of brush country stretching 150 miles between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande—was hazardous. “There’s not a lot of running water at all between those two rivers, there’s not a lot of shade, and it’s very hot,” says Roseann Bacha-Garza, a lecturer at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley and the co-author of Blue and Gray on the Border: The Rio Grande Valley Civil War Trail. “But if they had a horse, and if they had a gun, they could make their way through.”

Many runaways didn’t survive. Their stories, too, are worth preserving. “I consider them very important because it tells us the story that even when their flight was not recognized or when those individuals don’t leave records, the history still existed,” says Maria Esther Hammack, a doctoral candidate in history at UT Austin.

Born and raised in Mexico, Hammack knew Mexico abolished slavery decades before the U.S. did. But as a college student in the U.S., she was surprised to learn that questions like “Who was the Harriet Tubman that led people to Mexico?” and “How many people sought freedom in Mexico?” hadn’t yet been answered. These subjects have fueled her research ever since. She’s scoured archives and databases in the U.S., Mexico, and Canada for years to recover moving, if fragmentary, evidence of countless quests for freedom.

Hammack learned of an ill-fated union between a Mexican man and his enslaved wife, for example, not from first-person narratives but from an 1842 issue of the Telegraph and Texas Register newspaper. The couple took two horses and fled from Jackson County in South Texas, but they were captured near the Lavaca River. The man, likely an indentured servant or peon, was lynched on the spot. His wife, considered property, was returned to her enslaver—and captivity.

For those who did make it to the Rio Grande, there’s evidence that sympathetic multiracial ranching families who settled along the river would shelter fugitives and help them get to Mexico. According to local oral histories, the Webber Ranch and the Jackson Ranch, which were located along the Rio Grande in Hidalgo County, harbored runaways.

Diana Cardenas, a descendent of settler Nathaniel Jackson, learned about her family’s role in helping runaway enslaved people from her grandmother Adela Jackson, who was born on the Jackson Ranch in 1899 and lived nearby until her death at age 93. “There were consequences for helping and assisting runaway slaves,” says Cardenas, who maintains a collection of family artifacts. “Regardless of what the consequences were, my [ancestors] put people first.”

Leslie Trevino started studying the Webber family’s history after marrying a descendent of John Ferdinand Webber and his formerly enslaved Black wife, Silvia. “When you look up the slave hunters, there’s actually more information about them,” Trevino says. “There’s not a record of the people who made it to freedom, or who were caught, or who were fighting on the side of freedom. There are records of those who were fighting against freedom.”

Once in Mexico, the formerly enslaved continued to face great adversity and experienced freedom that, at best, was conditional, Mareite says. The escapees had few job opportunities and little community support. They lacked formal paperwork declaring them free, and they lived in secrecy under the constant threat of recapture by mercenaries. “So it’s not slavery,” Mareite observes, “but it’s not entirely freedom.”

This story was originally published in Texas Highways magazine.