Convincing American women to transform workplaces by voting in family-friendly laws involves no small amount of cajoling—and for good reason. Even after decades of feminist manifestos and women’s empowerment tomes (or perhaps partly because of them), it can feel like an admission of deficiency to clamor for a new world order, like you aren’t Oprah or Hillary or Sheryl enough to win in a man’s world.

That’s why personal growth books like Sheryl Sandberg’s “Lean In” are so seductive. They minimize the fact that the game is rigged, and make women feel like we alone possess the power to fulfill our highest career ambitions. They assert women’s capability and downplay their vulnerability in workplaces and communities that devalue them. We can succeed, the books say, if only we work hard enough, marry the right kind of person, time childbirth optimally or forgo it altogether. If, if, if.

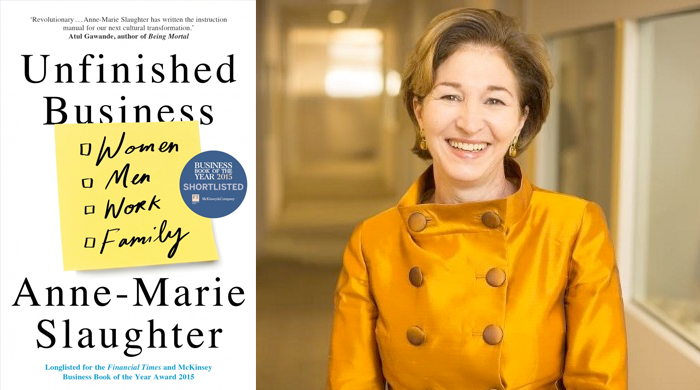

Anne-Marie Slaughter’s “Unfinished Business” does not make this mistake. Rather, it suggests that women have simultaneously taken on too much and too little of the burden of workplace progress — too much personal responsibility and too little collective action. We’ve taken exceptionally accomplished women as proof that we can do it too, when we should be more attuned to the innumerable ways American society is structured to hold most women down. Admirably, Slaughter attempts to outline them all.

“We Americans love self-help,” she writes. “Manuals that tell us to lean in or stand up or climb over others as a way to enhance our personalities, overcome our flaws, and assure our progress speak to a national religion of self-improvement. After all, if it’s only up to us, then change is within our control. It doesn’t depend on organizing or mobilizing others within a political system that many of us see as dysfunctional.”

As Slaughter sees it, individual work ethic is no match for the raft of workplace expectations, social customs and government policies that reinforce women’s (especially mothers’) second-class status at work. Children need their mother! It’s the man’s job to provide! Babies are focus-killers! Not to mention the absence of high-quality and affordable childcare and eldercare and paid family and medical leave — policies that would allow more women (and men) to earn a good wage while also being there for loved ones.

We do women a great disservice when we deflect attention from sweeping workplace and political changes like these that would actually make a difference. This becomes obvious when Slaughter examines women at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder and observes that they hold 62 percent of minimum-wage jobs. Half of single mothers make less than $25,000 a year, working in dead-end jobs with no flexibility or benefits. Motherhood is the single best predictor of impending bankruptcy among middle-class single women.

“It just isn’t plausible that too many women are at the bottom of American society because they are not trying hard enough, are too perfectionist, or lack confidence,” Slaughter writes.

As such, her vision for gender equality looks more like a denser social fabric than a shattered glass ceiling. That is, equality is not attained when women can scale the corporate ladder as high and as fast as men. Rather, equality emerges when our nation appreciates (and compensates) caregiving as much as breadwinning. Higher wages and training for paid caregivers, better enforcement of age discrimination laws, financial and social support for single parents, and greater early education investment are pieces of the care infrastructure she envisions. Another piece is raising our value of the unpaid, but vital, caretaking work of family members.

“The message that a woman’s traditional work of caregiving — anchoring the family by tending to material needs and nourishing minds and souls — is somehow less important than a man’s traditional work of earning an income to support that family and advance his own career is false and harmful,” she writes. “It is the result of a historical bias, an outdated prejudice, a cognitive distortion that is skewing our society and hurting us all.”

Slaughter writes that care (of children, aging parents, etc.) is the crucible that can unite women (and men) across the socioeconomic ladder. She doesn’t offer any specifics on how to build such a diverse coalition and bring about cultural transformation, however. Instead, she gives readers a list of policy ideas and a note to check the book’s endnotes for organizations and campaigns to support.

Robotically, she writes “the specifics of policy proposals on each of these issues differ from state to state and often by party affiliation and political philosophy; a comprehensive catalogue is thus impossible.” There’s a sea of opportunity between the eleven bulleted policy ideas she offers and a “comprehensive catalogue” of policy proposals, and it’s a serious weakness of the book that she doesn’t explore it.

In fact, Slaughter simply urges readers to elect more women to public office, as if that’s a specific policy proposal. “Indeed, given the wide-ranging support from everyday Americans of both parties for more government help for caregivers, it often seems as if our legislators are the only ones who aren’t getting the message,” she writers. “There’s a simple reason for that: we are electing too many men.”

This is a variation on the solution she offered in her much-debated 2012 Atlantic article, “Why Women Still Can’t Have it All,” which inspired this book. The article concluded, “We may need to put a woman in the White House before we are able to change the conditions of the women working at Walmart.”

That idea was in line with an earlier statement in the article: “I am writing for my demographic—highly educated, well-off women who are privileged enough to have choices in the first place…We are the women who could be leading, and who should be equally represented in the leadership ranks.” (Emphasis mine.)

In 2015, though, she’s rightly expanded her view to advocate for all women. Given that progress, it’s a surprise that she still sees electing women as a major catalyst for change, versus a symbol of it. It feels as naive as thinking all would be well with “black America” once President Obama was elected. Legislatures rarely dictate public attitudes; rather, public policy tends to ratify them. Unfinished Business, indeed.

If this post resonates with you, I bet you’ll enjoy my newsletter. I regularly send bookish news and notes out to more than 1,000 readers. Sign up here.