Wendy Lesser is the kind of reader who will track down a bootleg version of Haruki Murakami’s “Norwegian Wood” and compare it line by line with the authorized version. The kind of reader who can find a book list “intensely moving, even in its misjudgements.” The kind of re-reader who wishes “Wolf Hall” were twice as long and at its end heads to the Frick Museum to gaze at portraits of its protagonist Thomas Cromwell.

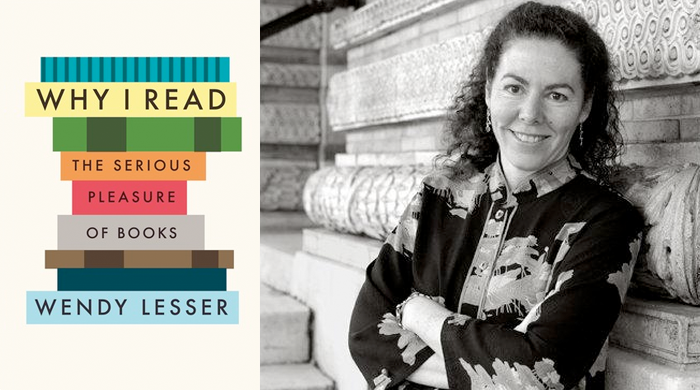

And she is the kind of writer who can spend 200 pages telling you all about her bookish tastes and beliefs without once urging you to agree. Her tone in “Why I Read: The Serious Pleasure of Books” is akin to a chatty hostess ushering you into her impressive library, fingering the spines of treasured books, and detailing the literary pleasures held within. She meanders through the shelves, pausing to recall a beloved passage here, some author backstory there. Sprinkling bon mots all the while.

Reading is not about progressing toward a finish line, any more than life is.

There is nothing shameful about giving up on a book in the middle: that is the exercise of taste.

In the never-ending conversation about what might count as good literature, there are many worse things than being wrong.

Her musings are informed and far-ranging. She explains why the sequels to great novels are often distinctly inferior. Praises 19th century Russians for setting the standard for writer authority and doubts nonfiction authors who fail to hint at their own unreliability. She quips that the TV show “The Wire” attained an air of “literary profundity.” (Surely, the highest compliment from such an inveterate reader.)

She’s generous, insisting that literature comes in all genres: poems, essays, mysteries, even sci fi–really, any form “well-written enough to last through multiple readings, not to mention multiple generations of readers.”

She hazards some guesses as to which contemporary literature might endure, and a quarter of the 100 books that she recommends for pleasure reading were penned by living or recently departed writers–not bad for a list that spans hundreds of years. Still, she devotes the most praise and attention to close readings of works of the white and dead. “The slight, the facile, and the merely self-glorifying tend to drop away over the centuries, and what we are left with is the bedrock: Homer and Milton, the Greek tragedians and Shakespeare, Chaucer and Cervantes and Swift, Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy and James and Conrad,” she explains.

She shares her reading opinions generously, but the account is scarcely personal. She holds her reader-guests at a respectful distance, limiting the conversation to the books, not the life of the reader. In just one odd passage about D.H. Lawrence, she risks personal disclosure. “I know of no book more true than ‘Sons and Lovers,’” she writes. “I would stake my life on its truths about mothers and their sons, young women and their lovers; I have staked my life on them, at key moments of emotional crisis or existential despair.” But she tells us no more about herself, her crises or her despair, quickly returning to thoughts on how Lawrence can browbeat the reader with his opinions and still allow space for them to choose to believe him or not.

Bibliomemoirs like “Tolstoy and the Purple Chair,” in which the author recounts her experiences reading a book a day for a year, and “The Shelf,” in which the author reads the New York Society Library’s LES-LEQ shelf, may feel inorganic and pat, but they provide a structure and narrative drive that “Why I Read” lacks.

And Lesser’s refusal to tell us what the books really mean to her, beyond an appreciation of admired writers’ deftness with character, plot and craft, ultimately prevents it from reaching its own literary ambitions. “A work of commentary or criticism is not necessarily a work of literature, but it can aspire to that condition and be the better for it,” Lesser wrote in the book’s prologue. “I aspire, in this little book, toward the qualities I have admired in novels and poetry, including the compression, the indirection, the inherent connections, the organic shape.”

A better choice would have been to aspire toward the kind of truth and authority she admires so much in 19th century Russian authors. It might have emboldened her to risk something in her writing and imbue quotidian observations of a reading life with the weight of hard-won revelation. As it stands, “Why I Read” is a delightful compilation of bookish insights. But it remains in the realm of scholarly conversation, not literature.

If this post resonates with you, I bet you’ll enjoy my newsletter. I regularly send bookish news and notes out to more than 1,000 readers. Sign up here.