Wordless picture books are excellent tools for practicing reading fluency. This crucial literacy skill is defined as the ability to read a text smoothly with rhythm, expression, and appropriate emotion—and it’s a key indicator of reading comprehension.

I first came across this novel use of wordless picture books in The Megabook of Fluency by Tim V. Rasinski and Melissa Cheesman Smith, and it struck me as a great example of building crucial reading skills without directly reading.

As such, it’s perfect for bolstering kids’ literacy foundation in those crucial years before they begin formal reading instruction, as well as a fun way to increase fluency among early or struggling readers.

With no words on the books’ pages, the labor of “decoding,” or sounding out words, is taken off the table. Instead, kids can focus on storytelling style and creating meaning—the heart of fluency. They can practice using their voices to embody an emotion or illustrate a point, and learn how to interpret and convey meaning out of details on the page.

To demonstrate how to use wordless picture books effectively, I invited Jessica “Culture Queen” Hebron, our favorite children’s performer and educator, to share her fluency expertise with parents.

Seven Steps to Fluency, with Jessica “Culture Queen” Hebron

Jessica Hebron, better known as “Culture Queen,” is a children’s educator who uses books and storytelling in her performances. Here is a step-by-step activity to build fluency via wordless picture books, enriched with her tips for how to “read” them with kids.

Since there are no words to read on the page, the narrative focus with wordless picture books shifts to interpreting and articulating the illustrations. When “reading” these books, how the illustrations are communicated holds great weight.

Narrating a wordless picture book is about using your imagination to make inferences regarding what the author/Illustrator was trying to communicate, but it’s also an opportunity to create your own interpretations. Remember, there are no right or wrong answers here, and finding novel ways to interpret the pictures can be part of the fun.

Step 1: Pick a great book. To develop fluency, you want to start with a book that sparks the imagination.

Look for a book with striking images that really tell a story. It should have some action, as well as pictures that lend themselves to dramatic expression. Illustrations that create mood or emotion are great for producing dramatic readings.

But while it’s critical that the pictures evoke a storyline, an element of mystery—some images that can be interpreted in different ways—can also keep kids especially engaged, creating fabulous opportunities for multiple readings and fun discussions on different ways of seeing things.

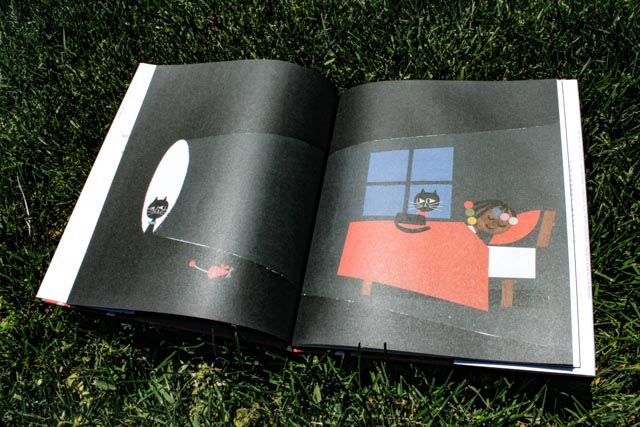

You can apply these tips to any wordless book, but in this post we’ll be using Another, by award-winning author-illustrator Christian Robinson, a lovely book reminiscent of a chocolate-covered Alice in Wonderland. The simple, construction-paper-like illustrations showcase a young girl and her black cat having an exciting encounter in a brand-new world full of adventure.

Together, the reader and the main character discover all of the portals, slides, chutes, ball pits, and stairs they can stand! Another cleverly, yet oh-so-gently, encourages readers to view the illustrations from several different angles. What Robinson always gets right is the positive way that he depicts children of color simply enjoying and exploring life—a revolutionary act in itself.

Bonus tip: It’s a good idea to examine book illustrations to ensure they don’t blatantly or subliminally communicate negative, demeaning, or stereotypical messages. Pay attention to how characters are represented on their own and in relation to each other. Children in the wordless-book age range may not be ready for deep discussions to contextualize messages you don’t agree with, and images internalized at a young age can exert a lasting influence for good or harm. Your best bet at this age is to keep a close eye on what you’re choosing to convey to your child about their world and possibilities.

2) Encourage kids to take a long look. At museums, curators often invite the patron to do “long looking” or “deep seeing” when gazing at art. This provides the viewer with space and time to truly see the art on their own terms. Allow your child to take their time examining the pictures before interpreting them. There’s no need to rush.

Creating meaning is a key aspect of fluency. Whether it’s developing a story from a set of illustrations or building meaning from the letters and words of a text, fluency is all about crafting understanding that comes to life from the page. Developing this skill with pictures will help children focus on meaning when they move on to sounding out words.

Struggling readers may manage to properly decode words, but they’ll read books aloud in a staccato monotone that betrays their lack of understanding. True reading success comes with comprehension on top of decoding, and you can build the foundation for this by helping children create and then convey meaning from illustrations.

When your child is ready, invite them to tell you the story and . . .

3) Listen actively. Allow your child to interpret the book at their own pace. Let their imaginations run wild while you both get sucked into the story. Resist the urge to correct them when they verbalize what is happening. This is their version, in their words.

If they need help getting started or continuing, ask open-ended questions, such as Can you tell me what’s happening here? How does their voice sound? or Who do you want to know more about?—without making it an interrogation. Other questions that might spark great conversation are: How does the character feel now? What are they thinking? Why did they do that?

If needed, skip on to step 4 and give your own dramatic reading of the text, to demonstrate the idea. After a few examples, kids are often more than ready to provide their own imaginative interpretations of wordless books.

We’ve suggested letting kids “read” the book first, to allow them to create their own stories without just mimicking the adult’s ideas, but mimicking is also an important way to build fluency—so feel free to mix up these steps however works for your child. The youngest kids, and those who are newer to being read to, often do best if the adult interprets the story first.

Practice patience while waiting to hear their responses, and you may be rewarded with some amazing insight into their inner lives and their interpretation of the world.

Next (or in a separate sitting if your child grows tired), it’s your turn . . .

4) Get into the story. Use the illustrations to inspire your own creative storytelling. When you tell your version, really get into the story and create an engaging narrative that brings the pictures to life for your listener, pulling them in.

Classic storytelling techniques passed down through the ages will serve you well in engaging your child and keeping them on the edge of their seat (or your lap, as the case may be). The basic formula here is action plus description—think lots of verbs embellished with expressive adjectives.

As an example, let’s take a look at the beginning of the story, and see how we might tell the story in these images.

Once upon a time, there was a sweet young girl named Zoe. Zoe loved many things. She loved wearing braids with colorful round beads in her hair that click-clacked each time she moved her head. She loved her beautiful black cat, Mr. Whiskers. She loved the warm and fluffy, ruby-red blanket she got for her birthday. But most of all, more than anything in the world, Zoe loved bedtime. In fact, she couldn’t wait for bedtime each night. Most kids her age were afraid of the dark, but Zoe just loved the pitch-black color of her room when the lights went out. Her beautiful black cat, Mr. Whiskers, however, was very afraid of the dark. The only thing that made him not scared was sleeping on top of Zoe’s warm and fluffy, ruby-red blanket.

5) Engage the power of repetition. Storytellers (and speech givers) from time immemorial have used repetition to draw in their audiences and drive their points home.

Repeating certain phrases will keep your little listener engaged and build a sense of momentum. As much as you can, try to refer to images that appear in the story multiple times (characters, objects, scenes) with the same phrase, tone, inflection, and rhythm.

As a bonus, repetition also helps with memory, and your child will be sure to try out these memorable expressions in their own retellings. As they attempt to recreate the phrasing that you’ve crafted (no doubt in their own cute rephrasings), they’ll automatically mimic the expression you gave the phrases as well, building their fluency (and vocabulary) in the process.

6) Model rhythmic, expressive speech.

Think of an actor performing on the stage, and all the inflections and moods they pour into the words they recite. Really pulls you in, right? Now, let’s see if we can recreate some of that expression in our own dramatic “reading.”

Playwrights often put notes in parentheses to indicate how the actor should articulate and emphasize a certain phrase. You don’t have to be a Shakespearean actor to read aloud to your children, but a little dramatic play-acting will go a long way toward holding their attention, helping them understand the story and develop fluency.

So now, I’d like you to try reading aloud the same narrative as above, but with more dramatic expression. Use the “stage notes” in parentheses as cues (but don’t read them aloud, unless you want to want to completely befuddle your little listener).

(Slowly) Once upon a time, there was a (lightly and softly) sweet young girl named Zoe. Zoe (with emphasis) loved many things. She (with emphasis) loved wearing braids with (vibrantly) colorful round beads in her hair that (make a clicking sound) click-clacked each time she moved her head. She (with emphasis) loved her (warmly) beautiful black cat (grandly) Mr. Whiskers. She (passionately) loved the (comforting) warm and fluffy, ruby-red blanket she got for her birthday. But most of all, more than anything in the (vastly) world, Zoe (enticingly) loved bedtime. (Matter of factly) In fact, she couldn’t (anxiously) wait for bedtime each night. Most kids her age were (with fear and angst) afraid of the dark; but Zoe just loved the (breathlessly) pitch-black color of her room when the lights went out. Her (warmly) beautiful black cat, Mr. Whiskers, however, was (anxiously) very afraid of the dark. (Honestly) The only thing that made him not scared was sleeping on top of Zoe’s (comforting) warm and fluffy, ruby-red blanket.

Practice adding this kind of expression to make your storytime go from monotone and mundane to mystical and magical in no time flat. It will also help your child develop the deep fluency that will enrich their eventual reading far beyond pure mechanics.

7) Discuss and reflect. After you do your dramatic reading, snuggle your child close for a chat about what you did with your voice and why. You might invite your child to try some of the same techniques.

Try pointing to selected pictures in the book and see if your child can identify and imitate how you read those parts of the story. For example, you can point to the “warm and fluffy, ruby-red blanket” or the “beautiful black cat” and see if your child will describe the pictures with the same words and inflection you used.

You can also ask open-ended questions about what different tones of voice convey, and how you can create different effects with your voice.

Bonus tip: A fun experiment is even to try to create different meanings out of the same phrases, just by changing the expression in your voice. Try reading the following sentences aloud, emphasizing the word in bold. They convey subtle shifts in meaning, don’t they.

- She never asked Mom for a cat.

- She never asked Mom for a cat.

- She never asked Mom for a cat.

- She never asked Mom for a cat.

- She never asked Mom for a cat.

This can lead to lots of fun and giggles, as you gently open up your child both to the full power of words and to the multiplicity of perspectives and interpretations possible in our world.

Happy reading!