Every day, in a hundred small ways, our children ask, “Do you hear me? Do you see me? Do I matter?

L.R. Knost

For most of my life, I’ve held the strong opinion that people talk too much. Among the documents I found when thumbing through files of my old assignments from my twelve years as an Akron Public Schools student in Ohio is an ode to succinctness that I wrote for an English class. In the poem, I call on people to “get to the point,” “keep things simple,” and—presumably for the sake of the rhyme—to avoid “dangling participles.” As an adult, I live for days when I don’t take calls or meetings and spend a full day reveling in silence.

So, imagine my surprise as a quiet-craving parent to discover that all the “let them catch you reading” stuff I’d seen on blogs and in parenting magazines was not critical for raising a reader, but making lots of conversation with babies and toddlers was. If leading reading by example alone isn’t a thing, I learned, parents had best use our voices to proactively bring kids’ attention to print and to build the oral vocabulary they need to make sense of words on the page.

I’m not the only parent who missed the memo about sparking meaningful conversations with kids, beginning in infancy. Studies of kids’ early-language environments show enormous differences in both the quantity and quality of talk that kids engage in with their families. Parent talkativeness varies for all kinds of reasons, from our personalities, stress levels, and time demands to our beliefs about what babies understand and cultural norms about kids’ proper role in conversation with adults.

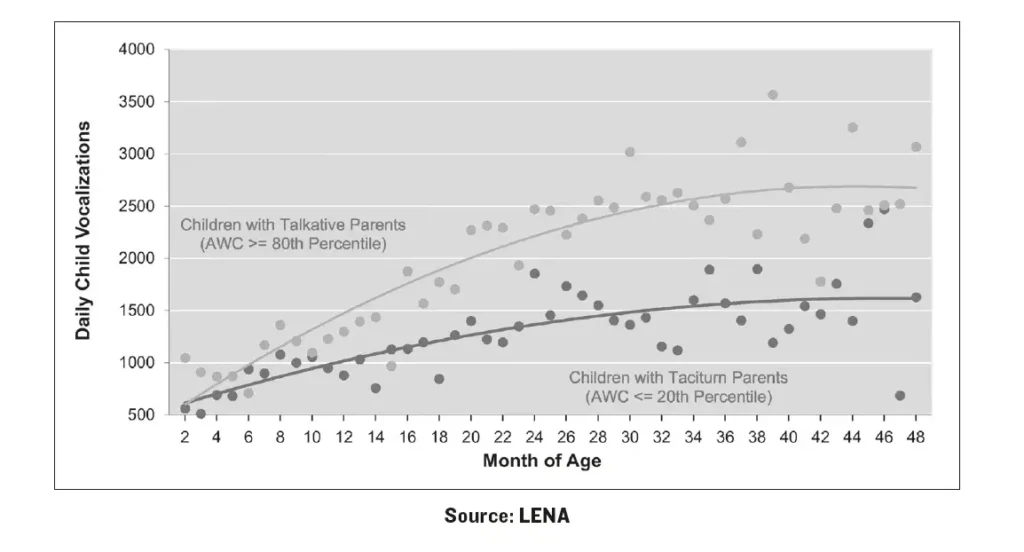

All of this matters because young children tend to follow their parents’ lead when it comes to how much they talk as they grow older. LENA, a national nonprofit that offers early-talk technology and data-driven early-language programs, compared the average daily vocalizations for kids who had parents with an Adult Word Count (AWC) in the highest versus lowest 20th percentile.

As you can see in the following graph of kids’ average daily vocalizations below from the LENA’s Natural Language Study, talkative parents tend to have talkative little ones and taciturn parents (caregivers who say little) have taciturn kids. And those differences in early language environments and early oral-language skills can have dramatic consequences for kids’ reading and learning outcomes years later.

This is the best illustration I’ve seen of the need for parents to say more to inspire kids to do the same. That is why I recommend working to build strong conversational rituals and routines into your family life as a key step to fuel your baby’s brain development and prepare them for reading. Experiment with different approaches to discover the ones that make you most able and motivated to converse more with the kids in your life.

And to the extroverts out there, you’re not off the hook. You should take heed as well, because parents of all stripes, from brusque to verbose, tend to overestimate how much we talk with our kids—and talking at kids isn’t the same as talking with them.

Edited and reprinted with permission from Reading for Our Lives by Maya Payne Smart, published by AVERY, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Copyright © 2022 by Maya Payne Smart.

Get Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six

Learn how to foster your child’s pre-reading and reading skills easily, affordably, and playfully in the time you’re already spending together.

Get Reading for Our Lives