School is a building which has four walls with tomorrow inside.

Lon Watters

In my book, Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six, I’ve endeavored to show parents why and how to play an active, hands-on role in helping their children become thriving readers.

But that’s not meant to suggest that parents should go it alone when it comes to turning their kids into readers. No one does. Every child’s road to reading is supported by a range of people, from the librarians who stock children’s books and host story time to the pediatricians who monitor developmental milestones and refer patients for additional assessment and care. Schools and teachers, in particular, are major contributors to reading development, when they are well-trained and well-supported in delivering high-quality instruction.

So part of the work of parenting for reading is being intentional about the formal learning spaces that we place our kids in. Fortunately, if you engage in the kind of everyday teaching and intentional conversation with kids around literacy that I advocate for in Reading for Our Lives, you’ll naturally acquire deep, first-hand knowledge of reading instruction. This will inform how you consider and select early childhood education centers and schools for your children.

When you have worked to build connection, vocabulary, and IQ through conversation; to bolster awareness of the sounds within words and the print in books and the environment; to teach letter names, shapes, and sounds; and to connect sounds to print and print to sounds, you can better recognize the education and childcare settings that will do the same. You’ll be able to spot the spaces and personnel that will help take your children’s reading to new heights.

This article will share a short list of items to look and listen for—and reflect upon—when you research and tour schools or childcare settings. However, I want to emphasize that you’ll best grasp all of these considerations if you’ve done the other talking, reading, and teaching work that I recommend. As Dr. Judson Brewer puts it, “Concepts don’t magically become wisdom with the wave of a wand. You actually have to do the work so the concepts translate into know-how through your own experience.”

It’s our everyday interactions with our kids, not studying reading instruction, that make us their best literacy advocates. What we do to engage our kids and what we learn about how they learn informs every other educational decision we make on their behalf.

How to Pick a Preschool or School That Boosts Literacy

Academic researchers look to things like teacher quality, curriculum, class size, environmental stimulation, and an array of other factors when assessing preschool quality. But I find that most parents typically have a much shorter list of selection criteria. Moms and dads focus on how close the options are to home or work, what the hours of operation are, and whether or not the places look clean and safe.

Only after those basic criteria are met (and if they have more than one viable option), do most then delve into the nuances of different curriculum and education philosophies, from Montessori and Reggio Emilia to Waldorf and HighScope.

When assessing options, I urge parents to tune into the sounds of the classroom and listen for the responsiveness, kindness, and knowledge on display. Just as children’s back-and-forth exchanges with their parents have a lasting impact on the kids’ brain development and academic prospects, dialogue and nurturing relationships with teachers matter greatly, too.

So, whether checking out in-home childcare, public-school pre-K programs, Head Start, or private preschool, here are a few things to look and listen for. All of these apply across the board when thinking about literacy in early learning spaces.

Back-and-Forth Conversation with Kids

Look for settings in which teachers have dynamic, nurturing verbal exchanges with each and every child. Just as parents provide critical language nutrition for their children, educators in infant, toddler, and preschool classrooms also spur vital nurturing, brain-building conversations.

So, when visiting classrooms or observing them via virtual tours, pay attention to how much teachers are talking with children; how well they are listening for kids’ responses, whether words, coos, or babbles; and whether or not each child in the space gets attention and conversation.

Class size, teacher inclinations and beliefs, and school culture can all affect word counts and conversational turns, and research has found vast disparities in how much talk different children within a space receive and give. Make sure your child is in a school where every child’s voice and participation is valued and encouraged.

Questions to Ponder

- Are teachers having nurturing one-on-one conversations with children, in addition to addressing small groups or the whole classroom?

- Are teachers pausing to listen for and respond to the children’s speech, whether words or babbles?

- What’s the ratio of direction/commands (e.g. sit down, be quiet) to conversation?

- Do the teachers speak to students with respect and value their expressions and classroom contributions?

Intentional Programming

Look for settings in which teachers can state what skills they intend to build, how they will nurture and assess them, and when and how they’ll communicate progress to families. The preliteracy and literacy skills that kids should be cultivating at different ages and stages vary widely, so be sure that the programs under consideration have a clear sense of what they’re teaching, why, and how.

For example, with infants, a teacher might share that they prioritize care, nurturing, and brain-building conversation—plus introduce books as objects of exploration, allowing babies to pat, chew, and turn the pages without expectation of great attention to the print or stories.

A teacher of toddlers might say they focus on giving children a variety of materials, letting them lead their own play, and encouraging them to create in their own way. The teacher might aim to provide a great deal of individual attention while also encouraging kids to try things on their own to see how far they get.

In a preschool program, you might expect more explicit discussion of the sounds within words and of letter names, shapes, and sounds, paving the way for formal instruction in phonics and spelling in kindergarten and beyond.

Beyond hearing the teachers’ intentions and method, also look for signs that they view parents as partners in educating children. Listen for assurances that they will keep you posted on what’s happening with your child throughout the year, so that you can continue to provide timely, responsive literacy support at home.

Questions to Ponder

- Do the teachers seem to enjoy their work and interactions with children?

- What curriculum or philosophy does the school follow? Is it accredited in the approach?

- What programs, degrees, certifications, or experience do the teachers bring to their positions?

- What blocks, toys, books, and other learning materials are on display? Do they seem to support the kind of learning the school says it emphasizes? How accessible are they to children?

A Joyful, Playful Environment

Look for settings in which kids are joyful, playful, active learners. When kids are deeply engaged in activities, and they have the freedom to play and explore the materials in their environment, good things will happen. During site visits, listen for the laughter and squeals of delight that characterize little kids’ engagement and discovery.

And, because we’re focused on reading, books and print should be an integral part of the fun of the learning environment. Look for books shelved in baskets, bins, and other spots that are visible and accessible to crawlers and walkers.

Watch to see if kids are given ample opportunity to handle books themselves. And observe how enthusiastic teachers are about discussing the stories, pointing out illustrations and print, asking questions of their little listeners, and fostering book love.

Questions to Ponder

- How happy and engaged do the children seem to be?

- Does the classroom or school foster a sense of community and connection?

- Are there age-appropriate materials to stimulate imagination, exploration, and discovery?

There is no perfect school, so it’s important to get clear about your highest priorities for your child’s learning environment and to listen to your gut feelings about the staff and spaces you visit. Tour schools with an open mind, open eyes, and open ears to find the options that will best serve your child and family.

Join my newsletter to get my best advice, recommendations, and resources straight to your inbox!

Wow, 2024 has been a heck of a year. I’ll never forget one moment in November, during a parent engagement workshop, when I saw the light bulbs going off for a room full of early childhood educators, librarians, and occupational and speech therapists. As we talked about how many had been approaching parents with the wrong energy and content—overloading them with demands instead of offering empathy and help—you could see their awareness dawning.

They began to realize the power of meeting parents where the parents are and giving them simple, impactful tools instead of homework. Witnessing that shift in understanding was so energizing and illustrated a big shift for me in audience and impact.

It felt like a full-circle moment for me, because I began the year with the launch of my Reading Made Simple online course. The course was my way of directly supporting parents with my best advice for guiding their children’s reading journeys at home—from day one. Some professionals enrolled, too, eager to see my approach to communicating family literacy best practices in an accessible, actionable way. This mix of serving parents directly and equipping professionals to amplify the message set me on a new path to commit to scaling my impact by “training the trainers,” so to speak.

Scaling Impact

When I compare 2024 to 2023, the growth and shifts in my work are clear. I found myself speaking to larger audiences over the past year, at bigger workshops and keynote presentations. And while numbers aren’t everything—I know that some of the deepest learning can happen in small, intimate settings—reaching more people is key to spreading this message widely.

That’s how we get to the tipping point of awareness about empowering families and activating whole communities for reading success. I’m proud that my work took me farther afield this year, as well, from Wisconsin to Louisiana, Iowa, Ohio, Maryland, Florida, and Idaho. Literacy needs love in every corner of the nation, and I’m so grateful to have been invited by such a wide variety of organizations to share the message.

This year also brought me to a bigger focus on early childhood professionals. I had the privilege of speaking for organizations including the Ohio Association for the Education of Young Children, the Maryland State Child Care Association, and KinderCare, to name a few.

Literacy is vital at every age, but starting strong with our youngest learners makes a world of difference. When we do a better job early, it helps everywhere down the line—from K-12 classrooms to colleges—because kids have a solid foundation to build on. This work left me feeling incredibly proud and energized.

At the same time, I dove deeper into the world of K-12 education. Even though my book, Reading for Our Lives, initially focused on birth-to-six literacy, reading achievement scores show that older kids often still need to develop those foundational skills.

This makes information on those skills and instilling them important for people working with kids up to 7, 8, and beyond—even through their teens! I began the year by presenting at the Wisconsin State Education Convention and went on to work with schools within the state and a New York school district as well.

One phrase I found myself saying over and over again this year was: Parents don’t want homework; they want help. And what I meant by that was that educators and those of us trying to influence families for the better should shift away from overloading parents with requests—checking folders and Google classrooms and email lists and robocall messages, maintaining reading logs, attending jargon-filled lectures, and so on.

Instead, we need to engage them in meaningful conversations. We need to focus on where their children are in their learning journeys, what’s required for them to advance, what the schools or support services can do to help, and how the parents can help in ways that fit with their strengths and the realities of their circumstances. Families are already juggling so much; they don’t need more to-dos. They need tools and strategies tailored to their reality that genuinely (and visibly) help their children succeed.

Through one-on-one conversations with educators and through consulting engagements, I helped schools reframe their messaging to parents. I urged them to tailor their advice to families’ real-world needs, so they can support kids more effectively. It’s not just about what we say; it’s about how and when we say it, so the message sticks and parents feel empowered to act. This behind-the-scenes work was as rewarding and felt as impactful as taking to stages more publicly.

Milestone Moments

A few pinch-me moments came this year, too. I learned that in February 2025, I’ll receive the Community Service Award from St. Francis Children’s Center at the Milwaukee Auto Show Gala and the Champion of Children Award from Foundations Inc. at their Beyond School Hours Conference in Orlando.

Joining the ranks of past honorees like Dolly Parton and Geoffrey Canada? Incredible! Both awards are wonderful affirmations that this work is resonating with people and making a difference.

And then there was the social media love! Imagine my surprise when Brené Brown shared a quote from my interview on her website about the joys of reading deeply, underlining, and writing in the margins. That single Instagram post brought a thousand new followers to my account. If you’re one of those folks who joined this community because of that post, welcome! I’m thrilled to have you here.

What’s Coming in 2025

Looking ahead to 2025, I’m feeling incredibly excited to keep this momentum going. I will reopen my Reading Made Simple course, this time with rolling enrollment throughout the year and tailored versions for parents and family support professionals.

I’ll also launch an updated and revised paperback edition (and audiobook!) of Reading for Our Lives in April, and I’m planning virtual book clubs and live events to celebrate. If you’d like to be part of the launch team or host an event, let me know—I’d love to make it happen.

If there are stages you’d like to see me on, states you think I should visit, or schools and districts that could use a fresh, responsive approach to engaging families in literacy building, please don’t hesitate to reach out. Together, we can keep empowering families and communities for reading success. Let me know how I can support your community’s literacy goals. Here’s to an even more impactful 2025!

Get Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six

Learn how to foster your child’s pre-reading and reading skills easily, affordably, and playfully in the time you’re already spending together.

Get Reading for Our Lives

Every day, in a hundred small ways, our children ask, “Do you hear me? Do you see me? Do I matter?

L.R. Knost

For most of my life, I’ve held the strong opinion that people talk too much. Among the documents I found when thumbing through files of my old assignments from my twelve years as an Akron Public Schools student in Ohio is an ode to succinctness that I wrote for an English class. In the poem, I call on people to “get to the point,” “keep things simple,” and—presumably for the sake of the rhyme—to avoid “dangling participles.” As an adult, I live for days when I don’t take calls or meetings and spend a full day reveling in silence.

So, imagine my surprise as a quiet-craving parent to discover that all the “let them catch you reading” stuff I’d seen on blogs and in parenting magazines was not critical for raising a reader, but making lots of conversation with babies and toddlers was. If leading reading by example alone isn’t a thing, I learned, parents had best use our voices to proactively bring kids’ attention to print and to build the oral vocabulary they need to make sense of words on the page.

I’m not the only parent who missed the memo about sparking meaningful conversations with kids, beginning in infancy. Studies of kids’ early-language environments show enormous differences in both the quantity and quality of talk that kids engage in with their families. Parent talkativeness varies for all kinds of reasons, from our personalities, stress levels, and time demands to our beliefs about what babies understand and cultural norms about kids’ proper role in conversation with adults.

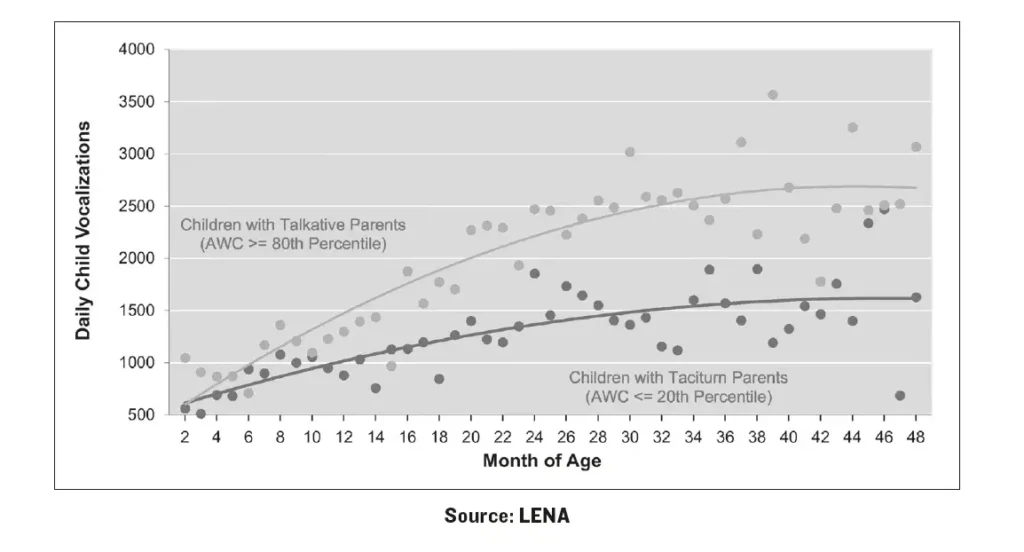

All of this matters because young children tend to follow their parents’ lead when it comes to how much they talk as they grow older. LENA, a national nonprofit that offers early-talk technology and data-driven early-language programs, compared the average daily vocalizations for kids who had parents with an Adult Word Count (AWC) in the highest versus lowest 20th percentile.

As you can see in the following graph of kids’ average daily vocalizations below from the LENA’s Natural Language Study, talkative parents tend to have talkative little ones and taciturn parents (caregivers who say little) have taciturn kids. And those differences in early language environments and early oral-language skills can have dramatic consequences for kids’ reading and learning outcomes years later.

This is the best illustration I’ve seen of the need for parents to say more to inspire kids to do the same. That is why I recommend working to build strong conversational rituals and routines into your family life as a key step to fuel your baby’s brain development and prepare them for reading. Experiment with different approaches to discover the ones that make you most able and motivated to converse more with the kids in your life.

And to the extroverts out there, you’re not off the hook. You should take heed as well, because parents of all stripes, from brusque to verbose, tend to overestimate how much we talk with our kids—and talking at kids isn’t the same as talking with them.

Edited and reprinted with permission from Reading for Our Lives by Maya Payne Smart, published by AVERY, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Copyright © 2022 by Maya Payne Smart.

Get Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six

Learn how to foster your child’s pre-reading and reading skills easily, affordably, and playfully in the time you’re already spending together.

Get Reading for Our Lives

Books help shape how children see themselves and the world, so exposing them to books by strong role models is powerful. Introducing young children to books by fantastic black women authors is a way to expand their world and nurture their love of reading while opening them up to their own potential.

For young black girls, seeing themselves reflected in stories can build confidence, affirm their identity, and show them what’s possible. And for all children, these authors bring rich storytelling with compelling characters and messages to inspire the next generation. Whether you’re looking for books about everyday joy, resilience, or history, these must-read black female authors have stories your family will love.

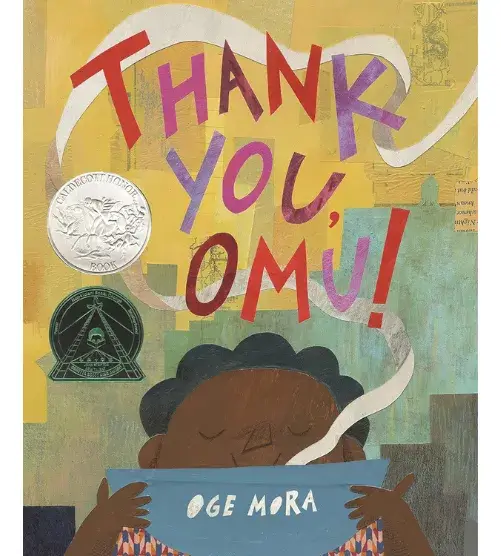

Oge Mora is a fantastic author-illustrator known for her vibrant, collage-style artwork and heartfelt narratives. She won a Caldecott Honor and Ezra Jack Keats award for her debut picture book, Thank You, Omu!, which celebrates generosity and community. In addition to writing, she also illustrates books for other authors, including Everybody in the Red Brick Building, The Oldest Student: How Mary Walker Learned to Read, and Shaking Things Up: 14 Young Women Who Changed the World.

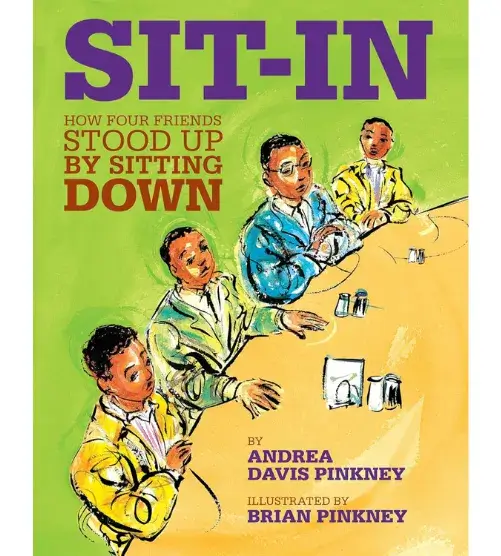

Andrea Davis Pinkney is a prolific author known for her powerful storytelling that highlights black history, culture, and resilience. From board books to chapter books, her work dazzles young readers with lyrical prose and rich narratives. She often collaborates with her husband, illustrator Brian Pinkney, creating stunning books like Sit-In and Martin Rising. With award-winning fiction and nonfiction, she brings history to life while celebrating black joy and excellence. Parents seeking inspiring black female authors will find her books must-reads.

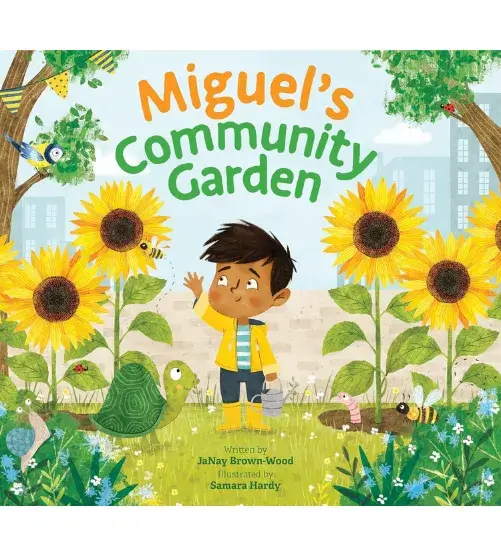

JaNay Brown-Wood is a children’s author, educator, and literacy advocate known for her joyful, engaging stories that showcase black families, nature, and community. Her popular Where in the Garden? series introduces young readers to fruits, vegetables, and problem-solving, through Amara’s Farm, Miguel’s Community Garden, Logan’s Greenhouse, and Linh’s Rooftop Garden. Her award-winning Imani’s Moon showcases themes of perseverance and dreams. With rhythmic language and warm storytelling, her books are perfect for parents seeking stories that reflect and uplift diverse childhood experiences.

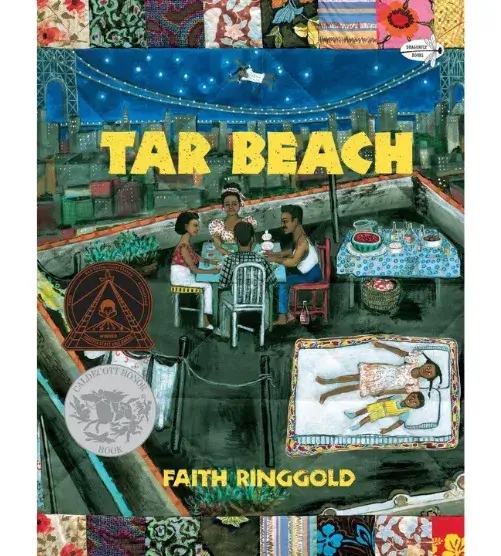

Faith Ringgold was an award-winning artist, author, and activist famous for her stunning story quilts and children’s books that elevate black history, identity, and resilience. Her iconic book Tar Beach won a Caldecott Honor and a Coretta Scott King Award, blending personal and historical themes with rich artwork. She also wrote We Came to America, a tribute to the diverse cultures that shape the United States. Her work continues to inspire young readers with its wonderful writing and artistry. You can also continue your learning and appreciation of Ringgold’s work by visiting exhibits of her quilt artwork in person or online.

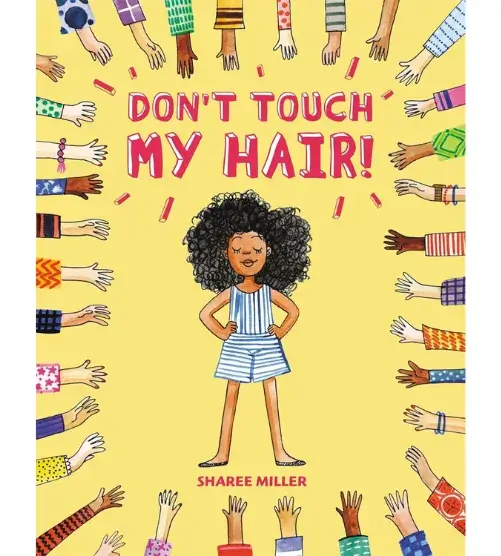

Sharee Miller is a children’s book author best known for her joyful stories celebrating black hair, self-love, and identity. Her popular picture books, including Don’t Touch My Hair! and Princess Hair, empower young readers with affirming messages and bright, playful illustrations that will draw kids into the story. In addition to being a writer, she also illustrated the book Michelle’s Garden, about Michelle Obama’s White House garden. Parents looking for confidence-boosting stories will love her books!

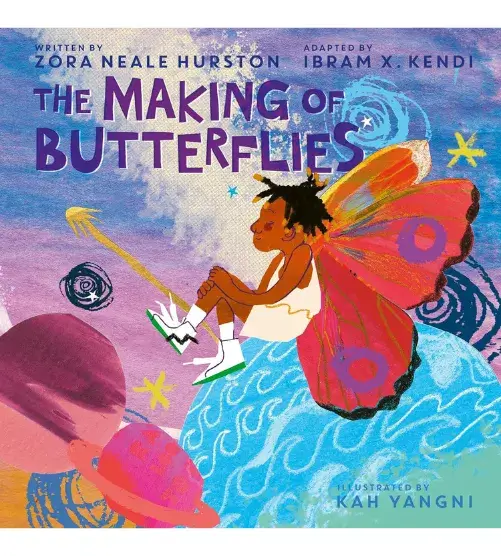

Zora Neale Hurston is an author most commonly known for her adult works, in particular the incredible Their Eyes Were Watching God. But Hurston also spent much of her life as a folklorist in Florida, collecting stories across the southern United States, Jamaica, Haiti, and the West Indies. In fact, she was granted a Guggenheim Fellowship twice to do this work! In the past five years, with a renewed interest in Hurston’s legacy, authors like Christopher Meyers and Ibram X. Kendi have been adapting and republishing these folktales into resplendent picture books. Be sure to check out The Making of Butterflies and (my personal favorite) Magnolia Flower.

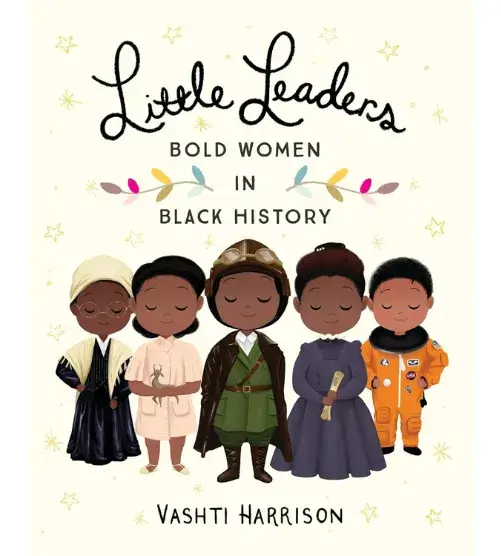

Vashti Harrison is deservedly acclaimed for her beautifully crafted children’s books. Her Little Leaders series, including Little Leaders: Bold Women in Black History, introduces young readers to inspiring figures with engaging prose and lovely, detailed illustrations. She has also illustrated books like Hair Love by Matthew A. Cherry and authored Big, a Coretta Scott King Honor book.

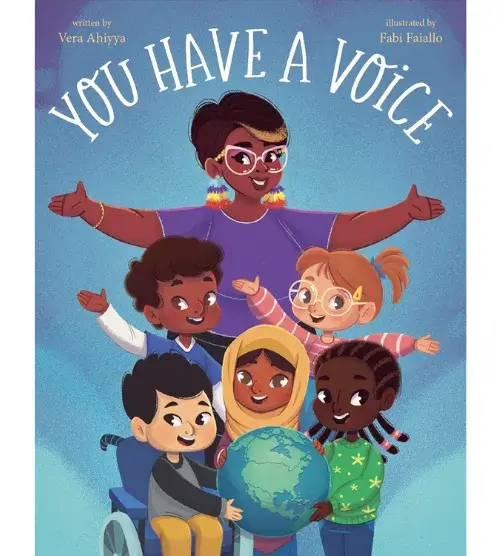

Vera Ahiyya is known as The Tutu Teacher. But in addition to being a teacher she is also a children’s book author and advocate for inclusive classrooms. Her picture books, including You Have a Voice and Rebellious Read Alouds, inspire young readers to embrace kindness and activism. She also writes books that help children transition into school, like KINDergarten and Getting Ready for Preschool!, which offer encouragement and reassurance for first-time students. Her Instagram page (@thetututeacher) is also a fantastic resource for books on any subject or theme.

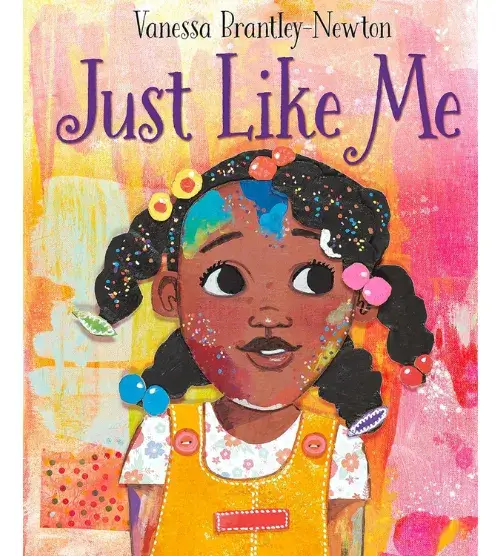

Vanessa Brantley-Newton’s stories, including Just Like Me, Grandma’s Purse, and Becoming Vanessa, celebrate self-esteem, confidence, and family bonds. Yet another multi-talented author/illustrator on our list, you can also find her art in award-winning books like The King of Kindergarten. With vibrant, expressive illustrations, her books spark giggles and excitement, making every page a delight for young readers. Her charming, affirming poems encourage children to embrace their uniqueness.

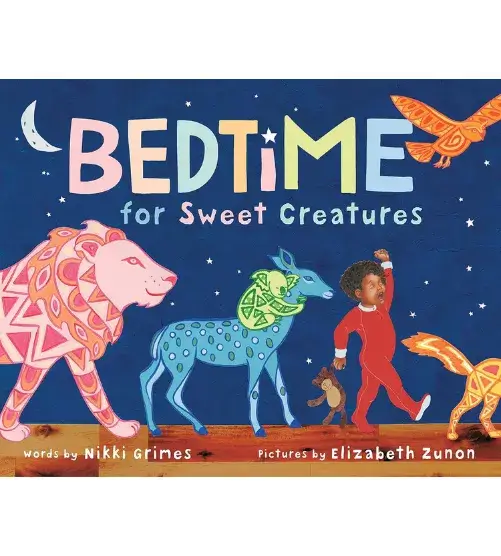

Award-winning author Nikki Grimes writes everything from picture books to novels in verse, including Bedtime for Sweet Creatures, Thanks a Million, and the Coretta Scott King Honor book Bronx Masquerade, a young adult book. Her work often highlights resilience, creativity, and the power of words. With rhythmic language and vivid imagery, her books draw young readers in and keep them glued to the page. Her stories offer a mix of warmth, honesty, and inspiration for children of all ages.

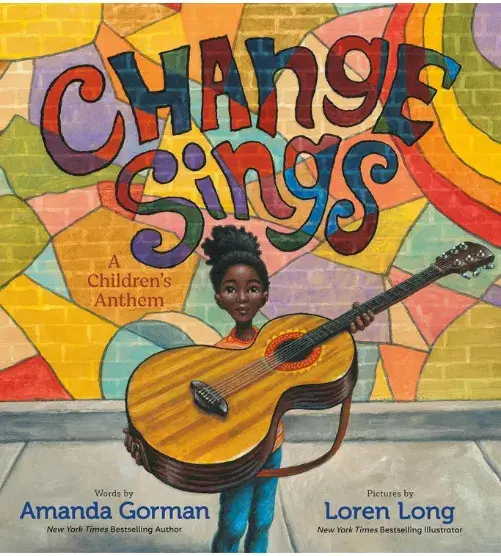

Amanda Gorman, the youngest inaugural poet in U.S. history, brings her powerful voice to children’s literature through beautifully crafted picture books. Change Sings: A Children’s Anthem and Something, Someday use lyrical language and strong messages to inspire young readers to make a difference in their communities. Her books encourage children to see themselves as changemakers, capable of kindness and action. With rhythmic storytelling and hopeful themes, her work introduces big ideas in a way that feels accessible and empowering for young minds.

The nation’s report card is in for 2024, and the results aren’t pretty. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) shows that far too many U.S. students are struggling with reading—and that on average, student learning has not bounced back since Covid.

If you’re a parent, it’s worth understanding these scores and what they do—and don’t—tell you. Specifically: What do these numbers actually mean? How do they affect your child? And what can we all do about them?

Here are five things you need to know about the 2024 U.S. reading scores. At the end, I’ll share three action steps all parents should take now.

1. The NAEP Test Offers a National Snapshot of Reading Achievement

The NAEP scores are often called “The Nation’s Report Card.” The assessment is a federally administered test that measures reading and math skills among U.S. students every two years. It’s not a high-stakes test—individual student scores aren’t reported, and participation is voluntary. But it provides critical insights into overall student performance across the country.

The 2024 results are alarming:

- National reading scores remain below pre-pandemic levels across all tested grades.

- Fourth- and eighth-grade scores dropped by two points from 2022.

- Less than a third of students nationwide can read grade-level texts with understanding.

- One-third of eighth graders scored “below basic” on reading skills—the greatest percentage to date. This means they struggle to identify main ideas or sequence events in a passage—skills critical for high school success.

NAEP scores fall into four categories:

- Below Basic: Struggling to recognize words, comprehend simple texts.

- Basic: Can read simple texts but struggle with deeper comprehension.

- Proficient: Can read and understand grade-level materials.

- Advanced: Highly skilled readers with strong comprehension and analysis.

The fact that so many students fall into the “below basic” category is a national crisis.

2. If Your Child Is Selected to Take NAEP, It Matters

The testers randomly assign students to take the NAEP test. The goal is to test a small, nationally representative group of students. Participation is voluntary, but the accuracy of the results depends on enough students participating.

No one will see your child’s individual test results or questionnaire responses—not you, your child, or their teacher. But they still matter, a lot. The results provide insight into how students in your district and state compare nationally. They also inform educational policy and resource allocation at the state and national levels.

But, keep in mind: NAEP scores don’t just reflect what happens at your child’s school and other local schools. Many external factors also play a role. Things like parents’ education levels, reading and literacy practices at home, outside tutoring, and the experiences kids have that build their vocabularies all affect reading performance, not just classroom instruction.

3. NAEP Is the Only Apples-to-Apples Comparison Across States

Each state sets its own standards for what qualifies as “proficient” on state reading tests, which means results vary widely. NAEP provides the only national benchmark.

For example:

- In Wisconsin, recent state tests showed 51% of fourth graders were proficient in reading.

- But NAEP told a different story. Only about 30% were deemed proficient by that nationally standardized measure.

This discrepancy happens because there are significant variations in the content of state assessments. States can set the bar as low or high as they want. As a parent, it’s important to look at all the data that’s available to you to really understand where your state, and more importantly, your child stand.

Want to see NAEP results for your state? Visit nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/ to see results, sample test questions, and more.

4. Covid Learning Loss Lingers—But Gaps Were Widening Before

The 2024 NAEP results confirm what many educators feared: Learning hasn’t recovered from school and home disruptions during the pandemic.

The biggest declines were among the lowest-performing students—those who were already struggling before Covid-19 hit.

At the same time, many higher-performing students have shown improvement relative to students tested in past years. The top 25% of eighth graders tested in 2024 actually scored higher than the top 25% of eighth graders tested previously.

The result? The reading gap is growing. In 2024, the difference in reading between the lowest- and highest-performing students widened to 100 points on NAEP’s 500-point scale. This reading skill gap has been increasing for over a decade.

This is sometimes called the Matthew Effect: The (literacy) rich get richer, and the (literacy) poor get poorer.

5. Demographics Aren’t Destiny—But Support Matters

NAEP scores show disparities by race and income level—but they don’t prove that certain students are doomed to struggle.

Instead, they highlight opportunities for action. These gaps signal a lack of early literacy support and systemic interventions long before children start school.

Kids from lower-income backgrounds often have fewer books at home, less exposure to rich vocabulary in their daily lives, and less access to high-quality early education. All of this contributes to the gap, but they aren’t inevitable. And all of it can be changed for individual children, and—with collective action—for all children.

Too many kids are struggling to read—and the gap is widening.

But reading outcomes aren’t set in stone. With family literacy practices, early intervention, high-quality instruction, and strong literacy advocacy, we can change the story.

Your voice matters. Let’s push for the resources and policies all our children need to thrive.

What Should Parents Do?

- Look at your state’s NAEP results and compare them to state test scores.

- Advocate for better reading instruction. Demand robust teacher training in structured phonics instruction and vocabulary building as well as intensive, high-quality tutoring for struggling readers in your district if they aren’t available already.

- Support literacy at home—early and often. Daily reading, talking, and writing activities make a big difference. See my book Reading for Our Lives for practical tips.

Remember those rhymes you used to chant as a kid? How about clapping and dancing to the beat of childish tunes? Perhaps you made up your own songs, not caring how silly they sounded. If you can see yourself doing that through the lens of your (much) younger self, you can easily teach phonemic awareness to your child.

But first, what is phonemic awareness? Most simply, it means hearing sounds—down to the individual sounds that make up words. Going one step farther, it is the ability to discern and manipulate the sounds within words.

The name sounds like a complex learning concept that requires some type of certification to teach. And, indeed, many children with dyslexia and other challenges may need specialists to help them master it. But it’s also something that you can—and should—begin nurturing at home in order to develop a solid reading foundation for your child. You can easily kick-start your child’s phonemic awareness with the types of activities you enjoyed when you were small.

Why Phonemic Awareness Matters

Before matching letters to sounds (phonics!), your child needs to grasp the idea that words are made up of sounds. That’s where phonemic awareness comes in. By teaching your child how to identify sounds and sound patterns within words, you’re setting the stage for the main event, which is phonics instruction.

As a mature reader, you may no longer pay much attention to individual sounds within words, because you’re so used to hearing and using them. Not so for small children. They’re absorbing these patterns by listening to people talk—and talking themselves—every day.

To accelerate this learning, you can use body movements, voice, and a few props to help your child become more aware of sound patterns and how frequently the same ones show up again and again in our spoken (and, as they’ll eventually see, written) language.

Once your child develops the ability to tell one sound from another, learning to read becomes much easier. Phonetically “decoding,” or sounding out, written words is a logical next step when your child can already break words down into sounds.

5 Easy, Fun Phonemic Awareness Activities

Convinced that phonemic awareness is central to learning to read? The following 5 phonemic awareness activities will get you started. Once you realize how easy it is to play with sounds, you’ll have no trouble coming up with new games on your own. And be sure to revisit those ditties you recited as a child! They’re full of rhymes, repetition, and recognizable sound patterns—fun for your child and fun for you.

Start by choosing a “sound of the day” and write the letter(s) that represent it somewhere handy to reference throughout the day. Introduce the sound to your child and give some example words that start with it. Point out an object whose name starts with the sound.

- Ask your child to find items in the room whose names begin with the sound of the day. As you go through your day together, point out objects that begin with the sound, and ask your child to do the same. For example, if your sound is /b/, you could point out their bed during nap time, a banana at snack, and a button when they’re getting dressed.

- Invite your child to think of things that start with the sound, then draw pictures of them together. (You can have your child think of the object, then you draw it for them or let them help draw it if they’re ready.) This expands their thinking beyond what they can see in the immediate environment, helping them apply the sound to other situations. You can also head outside and use chalk to draw pictures of items that start with the target sound on the sidewalk, driveway, or playground blacktop.

- Create a scavenger hunt. Hide some objects that begin with the sound you’re working on. Create clues for your child, using the sound as many times as you can. Repeat the sound at the end of each clue. For example: “The blue ball is hiding where Baby Bobby sleeps. B-b-b-b.”

- Make up silly songs using the sound. Create a tune and sing with your child, emphasizing the letter sound. For example, “Baby Bobby has a blanket. Baby Bobby has a ball. Baby Bobby blows bubbles!”

- Invent goofy sentences or short stories that use as many words starting with the sound as possible. Invite your child to act out the words or make up a dance to go along with the story. Here are some phrases to get you started: Buzzing Bumble Bee, Silly Sister Sally, Running Round Rose, Goofy Galloping Gary, Merry-Making Melanie, Lazy Little Lizard, Darling Dancing Dog.

By using these simple, fun activities to help your child identify sounds and sound patterns in words, you’re setting your little reader up for a future filled with good books, confidence in school, and a mastery of the English language. You’re also demonstrating from an early age that your child can count on you to help them learn new things as they grow!

Learning to read is the culmination of a long process that starts with learning to talk and then developing diverse skills and knowledge from vocabulary to the ABCs—not just the names of the letters or what they look like, mind you, but the sounds they represent.

These things take time. Kids don’t just recognize the 52 uppercase and lowercase letters—or distinguish similar ones like p and q—after seeing them once or twice. They certainly won’t remember the sounds the letters make, or the ways they combine to make various other sounds, without a lot of exposure and practice.

For the smoothest experience, kids should know as many letters and sounds as possible before entering kindergarten (or whenever they officially start learning to read). All that is why it’s crucial for parents and other early caregivers, from grandparents to babysitters to preschool teachers, to mix letters and literacy learning into daily activities with small kids.

Don’t try to cram it all into mega-lessons—it won’t work and it will make you and your child miserable. Instead, look for chances to include a little learning in playtime or routines with your child. Point out words on a cereal box or your child’s T-shirt, look for letters on signs outside, draw your child’s attention to the text of a recipe you make together, or mix a little writing into drawing time.

You can populate your home with fun prompts and reminders to practice letters and literacy with your child. In Reading for Our Lives: The Urgency of Early Literacy and the Action Plan to Help Your Child, Maya suggests that parents stock their homes with objects to spark little doses of literacy learning throughout daily life, like nursery rhyme mobiles, alphabet charts, waterproof books by the bathtub, or conversation cards on the dinner table.

And anytime you’re shopping for gifts for your child is a great moment to add some of these thoughtful, literacy-supporting toys and decor to your home. You can get intentional about birthday presents, Christmas gifts, Hanukkah gifts, or presents for Kwanzaa, Diwali, Eid—any time you want to surprise your little one with something special.

Have fun and get creative! There are so many unique and beautiful personalized gifts available that make letters, words, and reading a fun and natural part of your child’s day. To get you started, here are a few fun ideas for educational birthday or holiday gifts for kids that support reading skills:

Wooden Letter Train

So many small kids love toy trains, and wooden train sets can make a beautiful (and non-plastic!) addition to your family’s home. You can find lots of small producers on Etsy and other online marketplaces who make wooden train cars out of the letters of a child’s name. You’ll see a plethora of darling options like this train of letters with wheels or this train with letters topping small cars.

ABC Magnet Animals to Teach Letter Sounds

Letter magnets are ubiquitous and a fun way both to practice letters and eventually spell out words—but what if yours gave a clue to the sound the letters represent, too? There’s nothing about an S that tells kids what to make of the symbol, but an S crafted to look like a snake gives them a valuable hint. You can find gorgeous animal-shaped alphabets like this felt ABC magnet set. Of course, some of the letters are necessarily more of a stretch than others, but they can be a fantastic prompt for fun letter learning.

Nursery Rhyme or Storybook Rug or Quilt

If you’re fitting out your child’s space, there are lots of opportunities to enrich it with prompts to practice letters, recite rhymes, engage in oral storytelling, or read together. Rugs, quilts, or blankets with quotations or images from favorite nursery rhymes or tales are ideal for this purpose, and blankets in particular can make popular gifts for kids who love to snuggle up. As your child grows, they’ll be motivated to start trying to sound out the familiar words themselves, especially if you can find one with writing that’s easy to read. Create your own image with text on it for a custom woven cotton blanket, or find ready-made options like this Winnie-the-Pooh rug or an ABC blanket with your child’s name. There are even adorable doll-sized nursery-rhyme rugs for creative play.

Magnetic or Sticker Poetry

Magnetic words or word stickers that your child can use (with your help) to “write” their own simple sentences, messages, or stories are fun ways to build early literacy skills. You can read out the words and let your child arrange them into sentences at first—then, later on, they can sound out the words themselves as they create longer stories. The Magnetic Story Maker Kit is designed for kids to create fun, silly stories. The Magnetic Poetry line also includes various kits of easy words for children, including options in several languages besides English.

Name Puzzle—or Stool

Alphabet puzzles are popular, and you can find many beautiful wooden name puzzles that you can personalize with your child’s name (or even a favorite short phrase or quote). There are also fun twists on the concept, from name puzzles with animal shapes in addition to the child’s name to standing name puzzles, wooden name-puzzle stools, and even name-puzzle step stools with storage that could double as toyboxes.

Personalized Story Book

A picture book customized with your child’s name or that uses it for the main character can make a sweet gift to engage your little one in story time. You can find many options, like a personalized adventure story, a personalized alphabet book, or a personalized coloring and activity book that comes with letter crayons spelling your child’s name. Alternatively, you can make an even more unique tome by getting your own simple DIY storybook printed by one of the many photobook services, like Shutterfly or Google Photos. Illustrate it with photos of family and loved ones, your home, or familiar objects, then add some text naming who or what is in each picture—or even adding a little story of your own.

Personalized Holiday-Themed Gifts

You can also find or make all kinds of customized gifts for different holidays or events that add more letters and print into your child’s world. After all, even clothes with letters, words, or phrases can also be prompts to practice early literacy skills wherever you go with your child or whenever you have a moment together—provided you make it a point to use them that way. You’ll find endless options for different special events, from personalized Diwali treat jars to all-cotton personalized Christmas pajamas.

Story Advent Calendar

If your family celebrates Christmas, a story advent calendar can make an educational Christmas gift that encourages shared reading. Instead of opening a window every day to chocolates or toys—or pictures, when I was small!—your child will get to reveal a little story each day to enjoy together. There are a variety of niche options, as well as a Disney-themed storybook advent calendar, or with a little time and ingenuity, you could create your own!

With these ideas to get your creativity rolling, you can probably come up with many more variations on literacy-rich gifts for your little one and home. (Nursery rhymes on a personalized wall calendar? Book quotes or song lyrics on a customized T-shirt? The possibilities are endless…) The main point is to invest some of your time and thought into preparing your child for reading over the days and years to come. With a little information and intention, you can set your child up with the key skills to become a thriving reader. Reading for Our Lives gives you the blueprint of how to do that.

Then, of course, the next step is helping them learn to read well (and love it)—an even longer process that requires new elements, including ongoing exposure to challenging texts, spelling study, and deep, interactive conversation. But building a literacy rich home and, more importantly, the habit of engaging meaningfully and frequently with your little one are exciting first steps on this lifelong journey. Happy trails!

“Hi, Ms. Laila!”

The cheerful little voice calling across the schoolyard made me smile. I wasn’t a teacher, but after years of volunteering in my child’s class, I had become a familiar face. Seeing how comfortable my son’s classmates were with me was gratifying.

When my son started kindergarten, I offered to help once a week—despite having a two-year-old, being pregnant with my third, and juggling freelance work. I was busy and often exhausted, but the school let me bring my toddler along, and that made volunteering doable. It was adorable seeing her sit seriously at circle time or color alongside the “big” kindergarteners.

It turned out to be well worth the effort. Not only was I involved in my child’s education and helping our community, but I was rewarded with a level of personal fulfillment and connection that surprised me. That was, ironically, most valuable during the busiest, most tiring seasons of parenting, when it was most tempting to let volunteering slide.

Over the years, I tried to keep a presence in all my children’s elementary classrooms. The form that took changed with my shifting schedule, growing family, and different teachers’ needs—not to mention a long pause during Covid. At times, it felt like a chore I could barely fit in. But every time, whether I went in weekly, monthly, or a couple of times a year, the return on my investment was outsized.

I realize that work schedules, younger children, and other responsibilities make in-school volunteering difficult—or almost impossible—for many parents. But in my experience it’s worth thinking creatively about what’s doable. Even the busiest parent may be able to take a couple of hours off work once a year to help out.

Before you can volunteer, most schools require registration, which can take weeks to process. Get a head start—sign up now, even if you’re unsure when you’ll help. Once approved, check with your child’s teacher to see what’s needed most.

Here are my top 6 reasons for volunteering in the classroom.

It Supports Your Child’s Education

Classroom volunteering makes a direct impact on the students’ education—which is, after all, the point of school. Serving on the PTA, joining the school board, or planning fundraisers all make a difference. And contributing to your child’s schooling however you can is impactful and rewarding. To me, though, volunteering in class gets to the heart of the mission.

Schools are struggling to successfully teach all their students everything they need to know. This impacts everyone, and especially the most vulnerable children. (Read more about the U.S. reading crisis and its unequal impact in Maya’s article on national NAEP test scores, for example.) The education system relies on school volunteers to fill in the gaps of funding shortfalls and learning inequalities.

Helping in classrooms gives school volunteers the chance to directly support students in learning material they need to succeed in the next lesson, the next grade, and the next phase of life. As a volunteer, I’ve read one-on-one with students, practiced multiplication tables with small groups, supported science or art projects, and worked on spelling with kids just learning English.

With each math fact learned, new concept understood, or word sounded out, I could see a child’s path forward getting a little straighter and a little smoother. Along the way, I could also offer words of encouragement and individual support to children in crowded classrooms where the teachers were stretched thin.

It’s Good for Your Child

Volunteering in your child’s class shows them you care about them and value education. It also gives you a window into their academic and social needs.

That doesn’t mean you’ll be working with your own child. Sometimes, you may, but often, you’ll be helping others with individual, small group, or class-wide projects. And that’s a good thing. A thriving classroom benefits everyone—including your child. When all kids are learning and supported, the whole environment improves.

What’s more, kids will benefit throughout their lives if they’re part of a more successful, literate, competent, and fulfilled community. Conversely, they’ll all suffer if a significant number of their peers and neighbors are hampered by inadequate skills.

If your child feels jealous or neglected when you’re working with others, explain that you’re there to support them by helping the whole class succeed. You’ll help them feel better and also offer a valuable model of taking small steps to make positive change.

It Lets You Get to Know (and Support) Their Teacher

Volunteering in the classroom is also a wonderful chance to get to know your child’s teacher. This is meaningful in helping you better support your child’s education and may prove priceless if your child encounters any issues.

It’s also a huge help to teachers to have back-up during the school day. Elementary school teachers have to be “on” all the time—they can’t even take a bathroom break unless there’s another adult in the room.

They have to impart crucial foundational concepts to children who may be at wildly different levels of knowledge and skill development in each subject. On top of that, they have to help kids develop social skills, manage their emotions, and learn basic independence and organizational abilities from shoe tying to remembering their lunches.

At times, what teachers needed most when I volunteered was just for me to put papers in folders, make copies, or sharpen pencils. Those tasks are important, too. Anything that helps lighten the teacher’s load lets them focus more on teaching key material and supporting all the students. Sometimes, even just another grown-up around to calm a boisterous child or pick up some mess makes a big difference.

It Lets You Observe Your Child’s Class

No matter what my volunteer role was, I valued the chance to observe my children’s classes firsthand. There’s nothing like seeing with your own eyes how your child is doing and what their classmates, their teacher, and the overall environment are really like.

If you’ve ever had the experience of asking your little one about their day and gotten one word in return, stepping into their class may be just the ticket. Same thing if you have any concerns about their learning, attention, or behavior.

It can be heart-wrenching if your child complains about problems with other kids, a “mean” teacher, or hating school. Volunteering in the class can give you a clearer picture.

What sounds like bullying might just be normal childhood friction. Complaints about an unfair teacher might stem from the child’s frustration at not getting to chat during math time. And the little one who seems miserable after school may prove full of smiles, laughter, and genuine interest during class—just wiped out by the end of the day.

And if there are real issues to address, time in class may give you the insight to handle them appropriately.

No matter what, go into the class ready to help. Remove obstacles to success for the students and the teacher. Assume good intentions–from the teacher, the other kids, and your own child. If you find something unacceptable, address it politely. People are far more willing to listen when you’ve built a relationship and shown you’re there to support, not criticize.

It’s Good for Your Relationship with Your Child

Volunteering in the classroom builds your relationship with your child. It lets them know that you think their schooling is important and you’re willing to put in time and effort to support it.

Your physical presence also builds your emotional bank account with your child. It’s easy for kids to feel like their parents are always on the computer, on the phone, or at work. Never mind that you may be busy doing things that benefit them, from earning a living to attending a PTA meeting or planning their activities.

Volunteering in their classroom shows your child you care in the way kids, like all of us, understand best—with actions they can see. Keep in mind that you don’t necessarily have to put in a lot of time to reap the rewards. Showing up and being present makes an impact any time you can do it.

It’s Good for You

It can be hard to make room for one more thing, especially when we feel tired or overworked. (And what parent doesn’t, at least some of the time?) But doing something meaningful can be surprisingly rejuvenating.

Volunteering in your child’s class can make you feel happier, transport you away from your worries or responsibilities for a while, and give you valuable perspective.

Meaningful connection is vital to well-being, and it can be in short supply in modern life. Spending an hour or two with your child’s class may be a source of fulfilling connection that actually helps you to be more productive and energetic in other parts of your day.

That said, it’s important to recognize your own limits, too. If you can’t make it into your child’s classroom for a month, a year, or for years on end, that’s okay too.

If in-class volunteering isn’t possible for you, look for other ways to be involved and keep an open mind about trying it in the future. It also may be that you can arrange for a grandparent or another loved one to become a school volunteer.

Every family’s situation is different. The secret is to find what works for yours right now.

Slime! Kids just can’t get enough of it. It’s squishy, stretchy, and undeniably fun! I know some parents and teachers have a love/hate relationship with slime, but let’s turn that into all love. After all, kids adore it, so why not use it to have some fun together and help them learn?

Alphabet slime pairs messy play with meaningful early literacy practice. All you need is a few simple ingredients and some plastic alphabet shapes to make your own ABC slime packed with letters to explore. You can use alphabet beads, small magnetic letter shapes, or any other letter forms that are small enough to mix into your DIY slime.

More than just messy fun, this activity is a positive way to spark creativity and build important early literacy skills. I’ve found that this kind of tactile, hands-on learning can be a remarkable tool to help kids learn their letters faster and retain them more easily. Plus, the time you spend making it and playing with it together creates such special bonds and memories, which will help fuel their learning and development over the years to come.

Just follow the DIY alphabet slime recipe below with your child. Making it is part of the fun, so be sure to let them help mix it up. Once you and your little one have created your ABC slime together, use it for fun and learning! Your little one will love squishing, stretching, and exploring the slime while finding letters.

You can use it to help your child practice letter recognition, letter sounds, or even spelling. As you play together, simply tell them the names of the letters they find, if they’re just starting to learn the ABCs. Then you can explain what sound that letter usually makes.

If they know some letter names or sounds, ask them to try to identify the name or sound of the letters they find. You can also call out a letter name and ask your child to search for it in the slime. If they’re ready, call out letter sounds—for example, /s/—and have them locate the letter that makes that sound.

Once your child can read, you can even turn ABC slime into a tactile word search! Give your little reader a word to spell with their slime. This could be a spelling word they’re learning, a word they’ve struggled to read, or their own name for a budding reader. (Just be sure your slime has the necessary letters, for example if there’s a double letter in the word.) Then have them search for the letters to spell it. They can easily pull apart the slime to separate the letters to spell a word.

Adapt to your child’s level and the skills they’re learning, and be sure to keep it light and fun. (See How to Teach Your Child the Alphabet for more tips.)

ABC slime is a fun and easy DIY learning tool that’s adaptable for children as they age and their literacy develops. Even better, it’s inexpensive—or free if you have supplies on hand and letter beads or magnets to upcycle!

Ready to mix up some fun? Let’s get started!

DIY Alphabet Slime Recipe

Ingredients

- 1/2 cup clear or white PVA school glue

- 1/2 cup water

- 1/2 teaspoon baking soda

- 1 tablespoon saline solution that contains boric acid (check label)

- Alphabet beads, foam letters, or ABC magnets

- Optional: Food coloring or glitter

Instructions

Step 1: Combine 1/2 cup of glue with 1/2 cup of water in a mixing bowl. Stir well.

Step 2: Stir in 1/2 teaspoon of baking soda until fully dissolved.

Step 3: Add your letters and stir to mix evenly. Pay attention to the letters you include. For example, put in letters your child is learning and maybe all the letters of their name, including two of the same letter if needed. If you want to add food coloring or glitter, also add it now.

Step 4: Add 1 tablespoon of saline solution and mix. The slime will begin to form.

Step 5: Knead the slime with your hands until it gets stretchy and less sticky. Add a few more drops of saline solution if the slime is too sticky.

Store your slime in an airtight container, and you can pull it out anytime for a playful learning experience.

When I wrote Reading for Our Lives, I envisioned it aiding a busy mom—someone hustling through the whirlwind of life with young children, but with an eye on preparing them for success in school and beyond. For her, I filled the book with practical everyday strategies to weave literacy into the fabric of family life, from mealtimes and diaper changes to errand runs and playground jaunts.

What I didn’t anticipate was how much the book would resonate with civic leaders, corporate professionals, and others who were far removed from diaper duty but drawn to the power of literacy to shape communities. One such reader is Kevin Long, a commercial litigation attorney at Quarles & Brady in Milwaukee.

Long didn’t set out to become a literacy advocate. But through a journey driven by a series of questions—he’s curious, persistent, and purposeful—he’s become a catalyst for change, urging Milwaukee’s business community to invest in early-literacy initiatives.

Recognizing Root Causes

For Long, service to others has always been central to his life. Guided by Jesuit principles of being “men and women for others,” he and his wife, Peggy, have long sought ways to uplift their community. Professionally, Long drew inspiration from leaders at his law firm, especially attorneys John Daniels and Mike Gonring, who modeled giving back.

When Long heard me speak about early literacy at a Fellowship Open event, a charity golf weekend benefitting youth empowerment programs, something clicked. He left with a copy of Reading for Our Lives, read it, reflected on it, and asked himself, What does this mean for Milwaukee?

He connected the dots between what he read in the book and what he’d witnessed in local schools. “In almost all of them that you talk to, they all correctly state what a great job they do with their students and how much their students learn,” Long shared. “But they will always say that far too often the students come to them, whether they’re a high school or a grade school, and they’re a little bit behind and we need to catch them up in this way or that way.”

Reading for Our Lives helped him see the bigger picture—that success in the K-12 years or even college doesn’t start there. “The development of any person begins in the earliest years,” he said. “The more you can do in the beginning years of a child’s life, the better you’re going to set them up for success down the road.”

Turning Skepticism into Momentum

Inspired but cautious, Long started small. He didn’t make a grand statement or lead a large campaign. Rather, he began hosting meetings with civic and educational leaders, researching existing programs, and asking thoughtful questions. One of his key discoveries was Reach Out and Read, a program that integrates books into pediatric well-child visits, equipping parents with tools to foster reading habits from birth.

“I looked at things skeptically and said, What’s proved to me that this is going to work before we go ask people to invest a lot of money in this?” he explained. What he found was a program with strong evidence, clear goals, and a powerful framework for reaching families through healthcare touchpoints. “When you have a new birth in your family, there’s an invigoration of everything around that child,” Long said. “That sort of energy helps families coalesce around a strategy to do the best for their child.”

Long’s curiosity deepened: Why don’t more families have access to this? What can I do to help? These questions became the foundation of his advocacy. He championed the program, even convening local foundations and philanthropists to explore its potential.

“Milwaukee is small enough that people who care about something will run into each other,” Long noted. “That’s a huge advantage when building relationships and driving change.” His efforts culminated in a single meeting that raised over $100,000 for Reach Out and Read. For his leadership, Long received the organization’s Stellar Partner Award—a testament to the power of thoughtful questions and bold action.

Your Turn

Long’s story proves you don’t need perfect answers or grand plans. Advocacy starts small—by showing up, listening, and asking thoughtful questions. What’s at the root of the problem? Who’s already working on it? How can I help?

Curiosity, not certainty, drove Long’s success. His questions unlocked funding, built partnerships, and expanded early literacy efforts across Milwaukee.

Change starts with curiosity. It grows with connection. And it leads to concerted action. So why not start with a question of your own? Why not you?

Get Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six

Learn how to foster your child’s pre-reading and reading skills easily, affordably, and playfully in the time you’re already spending together.

Get Reading for Our Lives