Learning that letters represent specific sounds is a major development on the road to skilled, fluent reading. But the way it happens for most kids is a slow dawning of recognition over time, as children gain experience with the 52 uppercase and lowercase letters. For this reason, it’s critical for parents to make a habit of regularly bringing kids’ attention to letter shapes, names, and sounds over their early years.

A three-year-old named Beth, for example, might know that the letter “B” says /b/ in Beth. She might recognize and point to the letter on signs or in books, and even say “that’s my letter.” But that doesn’t mean she also understands that B says /b/ universally—like in bus, banana, or bowl. And it could take weeks, months, or years for her to make connections between other letters and the sounds they make, such as knowing the letter X says /ks/ or N says /n/.

How quickly children connect written symbols to sounds comes down to exposure and practice. It matters (a lot) how frequently grownups call the kids’ attention to print and discuss specific letters and their sounds. Preschool-aged kids who see and talk about letters more will learn them faster, while kids who see them less—or not at all—will struggle later in school.

That’s why parents are the perfect candidates to teach the alphabet. As a parent, you have ample opportunity to talk about letters while going about daily life with your little one. With just your voice and the letters around you (in books and on signs, t-shirts, cereal boxes, etc.), you have all you need to help kids learn their ABCs.

Moreover, relying on school alone to teach kids their ABCs is a losing strategy. One study of 81 preschool classrooms found the teachers spent an average of just 2.77 minutes a day teaching letters. The rest of the time they focused on other important self-care, social-emotional, and pre-academic skills. Imagine how easily you could double that time at home and target the lessons to your child’s level.

The Best Way to Teach the Alphabet

So how should you teach the alphabet? The best way to start is with some simple, direct teaching. After that, it’s a question of practice and repetition, which can be easily accomplished through play.

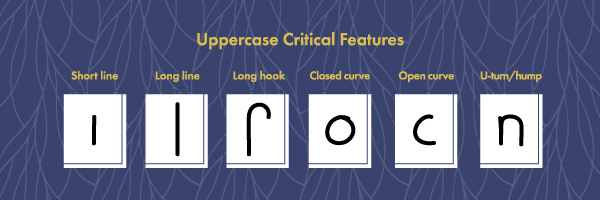

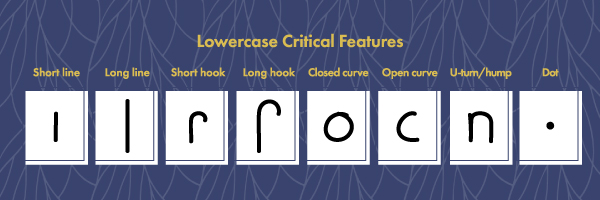

To begin, just draw your child’s attention to letters and their component parts. Critical features to point out within letters include short and long lines, open and closed curves, hooks, humps, and dots. Bonus points if you refer to these letter parts consistently (e.g. short line, long line, hook, curve) so that kids grasp that they’re used to form various letters. For example, you can point out the “long lines” that appear in A, B, and D, as well as the curves in C and G. Similarly, you can help kids notice that the features can vary in orientation (horizontal, vertical, diagonal), size (height, width), overlap, and more. Paying attention to these features helps with both letter recognition and letter formation (writing).

Research suggests that elements like where curves and lines terminate and intersect help people distinguish among letters. When children begin trying to write, they engage more actively with the shapes of different letters and pay greater attention to their distinctive features (e.g. curves, humps, and dots). But even before kids have the motor skills needed to write, you can introduce them to forming letters by giving them laminated letter-part cutouts to assemble into letters.

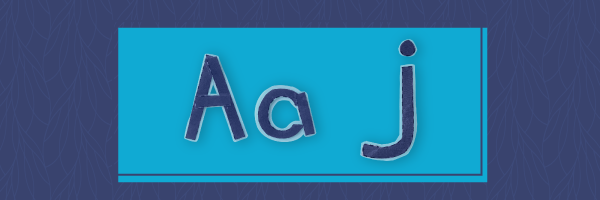

For example, a capital A would be constructed from two long lines and one short line. A lowercase j would feature a dot and a long hook.

There are countless opportunities every day for you to point out letters in the books you read to your child or on signs and labels in your home or neighborhood. But you can also just whip out a sheet of paper or index card, write a letter on it, and talk to your child about it.

How to Talk about Letter Shapes, Names, and Sounds

It’s a surprisingly powerful literacy lesson just to say something as simple as This is the letter T. T says /t/ like in taco. T is made from one short line (trace across the top of the letter) and one long line (trace across the vertical line). In a matter of seconds, you’ve brought your child’s attention to a letter, given its name, highlighted its main sound, and traced its shape.

In fact, talking about letters may be one of the easiest and highest return-on-investment activities parents can do. Over time, these light touches will stick the ABCs in your child’s memory. You’ll build their knowledge of English’s 26 letters, the ways they combine to form 44 different speech sounds, and the 52 different ways we write them (uppercase and lowercase). And you’ll pave the way for them to sound out hundreds of thousands of words. It’s no wonder that letter knowledge at kindergarten entry is a significant predictor of reading skills down the road.

You can describe the lines and curves within the visual forms of letters, comparing and contrasting the shapes of different letters, for example comparing a lowercase “b” and “d.” You can write a “c” and draw a cat next to it, pointing out that the word begins with the /k/ sound. And so on.

I’m highlighting this kind of direct, straight-forward teaching of letters (individually, in isolation, and outside of words) because sometimes our preconceptions about what’s “natural,” “meaningful,” and “enjoyable” in young children’s learning get in the way of doing what’s effective and efficient.

A review of four randomized control trials of letter instruction for three- and four-year olds found that teaching letters on their own was more effective than teaching them while reading a book or within the context of words or names—and it was fun, engaging, and motivating to boot. Think about it: Letter lessons delivered during storybook reading have to compete with all the wonderful images and stories unfolding on the books’ pages.

That’s not to say that there’s no benefit to teaching letters within the context of books or everyday signage. In fact, you absolutely should do that, too. It’s just to say that it’s not the first or only way you should be teaching letters. It’s critical to teach literacy skills in meaningful contexts (in this case, within words) as well as in isolation. How else would kids learn what letters are for and how they connect with sounds and meaning? There are some books with large, bold letters and sparse illustrations that are perfect for drawing attention to print. They’re entertaining for kids and provide valuable prompts for parents to remember to talk about print. (More on this below.)

The point is: It’s best to teach letters in and out of context. Giving a specific lesson on a specific skill or a single letter isn’t tantamount to “drill and kill”—provided you keep it brief, light, playful, and responsive to your child. Key elements of education are practice, repetition, and “retrieval”—which is a fancy way of saying bringing knowledge up from memory—even with three-year-olds. So go ahead, give some five-minute direct letter lessons now and then.

It makes sense developmentally to start with uppercase printed letters, because they’re easier for kids to recognize than lowercase and handwritten letters.

A Simple Letter Lesson to Try

Just remember to keep it light and easy. You can create impactful letter experiences with young children in ten minutes or less. A home letter lesson, adapted from this instructional progression idea, might look like doing the following:

- Pick a letter.

- Write it on a piece of paper, say its name, and most common sound. This is the letter Z. Z says /z/.

- Describe its lines, curves and other distinctive features while pointing to or tracing them. Z is made of three lines. Two short and one long.

- Ask the child to trace and describe the featured letter parts one by one (e.g. lines, curves, dots). Can you trace the lines of the Z with your finger?

- Ask the child to write the key letter parts on whatever surface and whatever materials are handy (e.g. pencil on paper, shaving cream on the side of the bathtub, on the sidewalk with chalk). Can you draw one long and two short lines on this piece of paper?

- Ask the child to combine the features to form the letter. (Or, if their motor skills aren’t there yet, ask them to assemble the letter by combining letter-part cutouts.) Can you write a Z made of three lines?

This approach gives the child a bit of runway as they approach writing the letter. It gives them repeated opportunities to see the letter’s visual form while hearing its name and it breaks down the component features needed to write or build the letter.

How Kids Learn to Recognize and Distinguish Among Letters

As readers ourselves, parents often fail to grasp what a leap it is even to see letters as distinct from other images and graphics in print. To know an O from a circle or an H from a stick figure is the result of a long learning process, a slow-growing awareness of print and its properties. At first, pictures, letters, and numbers are all a bunch of 2D marks to be deciphered.

Children begin to be able to distinguish different things they see as infants. However, it takes years for them to develop the ability to differentiate letters from one another and from other letter-like forms. After all, all letters look very, very similar to one another when taken in the context of most other “objects” kids are learning to distinguish visually.

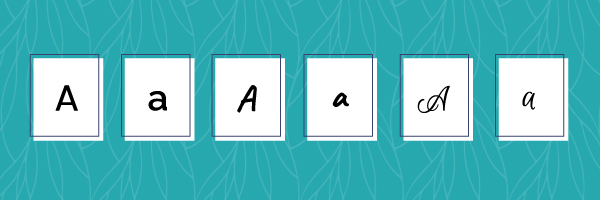

Eventually, they come to easily distinguish letters from numbers and other visual forms with letter-like shapes. They also tend to learn printed uppercase letters before lowercase letters and handwritten letters. As kids get older and gain more and more experience with letters in print, handwriting, cursive, and various fonts, their ability to discern letter variations and distortions grows. That is, they come to know that all of the following, despite different cases and fonts, are As.

The sequence of letter-learning varies among children but, generally speaking, kids learn:

- Letters in their own names before other letters

- Uppercase letters before lowercase letters

- Printed letters before handwritten letters

- Letters early in the alphabet (A, B, C) before letters later in the alphabet

- The sounds for letters when the letter name gives a clue (“dee” for duck) before sounds for letters whose names don’t contain the letter sound (“double-u” for Wednesday)

- Sounds for letters with a single sound (e.g. /b/ for B) before sounds for letters with multiple sounds (e.g. /k/ and /s/ for C)

Teach & Practice the ABCs Through Play

As a parent teaching your child the alphabet, there are many different ways to deliver the letter lessons described above. You can point out letters as you play with alphabet blocks, write them for your child in glue or glitter, form them from playdough, and so on. Mixing the learning in to playtime with your child will keep it fun and engaging for them (and you).

Once your child is familiar with some letter names, shapes, and sounds, practice and repetition become especially important. It takes years to commit all those to memory, so finding fun games and crafts to reinforce the learning is powerful. Below are links to numerous activities you can do with your child to help them learn the names, shapes, and sounds of the ABCs.

Letter Name Games

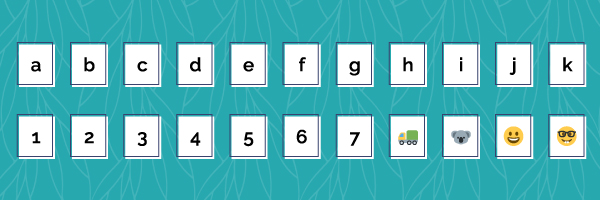

Sure, you could hold up a card with a letter on it to find out what letter names your child knows. But if you call it a game of War and have them play against you, suddenly it’s transformed into something more lively and engaging. The same goes for naming letters on a board game, hopscotch squares, a soccer ball, or a scavenger hunt. Some letter-name practice is just more fun as your kids work to learn to correctly identify all 52 different uppercase and lowercase letters.

- Alphabet Game of War

- DIY Alphabet Board Game

- DIY Alphabet Fishing

- Alphabet Soccer

- Alphabet Hopscotch

- Outdoor ABC Scavenger Hunt

Letter Shape Activities

Nothing helps a child spend sustained time thinking about letter shapes better than an activity that gives them a chance to form a letter themselves. It also gets them in tune with the lines, curves, and intersections of letters even before they have the fine motor skills to write them with a skinny pencil. Give any or all of these activities a try to create fun time learning letters.

Letter Sound Play

I love The Name Game (Bananafana fofana fi fi fofana banana) for giving kids practice manipulating the sounds within words, attuning their ears to the different sounds that make up language—a crucial skill for later reading, writing, and spelling. But little ones also need to learn which sounds map to which written letters, and parents could use a slew of activities to provide that critical practice lightly over time.

- Wheel of Phonics

- Sound Search Game

- Pretend Alphabet Soup

- Alphabet Bingo

- All-Day Alphabet Scavenger Hunt

- Outdoor ABC Scavenger Hunt

- Alphabet Hopscotch

- Alphabet Soccer

- DIY Alphabet Board Game

- Alphabet Game of War

Seasonal Letter Fun

Getting your child’s attention is half the battle with anything you want to teach. And sometimes a seasonal hook is just the way to get your child in the letter-learning spirit. Here are some Thanksgiving, Halloween, Christmas, and Valentine’s Day activities to infuse a little learning into the holidays:

- DIY Turkey Letter Matching Game for Thanksgiving

- Christmas Alphabet Flipbook

- Halloween Alphabet Spinner

- Valentine’s Day ABC Memory Game

Tools for Teaching the Alphabet at Home

You can teach your child the letters of the alphabet with a little knowledge, a dab of confidence, your voice, and your pointer finger, for example using the scripts above. But using some external tools can help make the necessary practice and repetition more fun for them—and for you. Index cards, letter tiles, and alphabet books top my list of go-to tools, but there are lots of resources you can use to reinforce letter learning. Draw from the list below, and click on each tool to learn more and get inspiration for how to use it:

- Playdough

- Stacking Blocks

- Index Cards

- Letter tiles

- Comic Sans

- Craft Sticks

- Letter Tracing Sheets (free printable)

- Alphabet Books

Teaching with Alphabet Books

You can and should teach with whatever letters you find in your everyday environment, from the grocery store to the bus stop. But carefully curated books also create great opportunities to bring kids’ attention to print. And well-chosen alphabet books, in particular, can make letter teaching a snap for parents. Displaying quality ABC books in your home will create wonderful prompts to spend much-needed time engaged in letter talk with your child.

Numerous studies suggest that alphabet books prompt parents to talk about words, letters, and the writing system more than other kinds of picture books. While reading ABC books, parents naturally reference letters, count letters, separate words into individual sounds (also known as phonemes), and ask kids to do the same. All of this letter talk helps kids understand that printed text represents spoken language—and it builds their bank of letters and words they know.

When reading typical picture books, by contrast, parents are less likely to even draw kids’ attention to the print, much less to dig into the form, function, and features of written language. You’re understandably busy reading the story and talking about the book’s plot, illustrations, or connections between the story and the child’s life.

Don’t get me wrong: There is tremendous value to reading all genres of picture books, and those other kinds of read-alouds and conversations are crucial for developing vocabulary, comprehension, and book love. It’s just that when your aim is teaching letters, alphabet books are a wonderful choice. They make it easy to stay on task, provided you choose the right kind of ABC books.

Alphabet Teaching FAQs

At what age do kids need to know the alphabet, and when should parents start teaching them?

Kids should recognize all uppercase and lowercase letters of the alphabet by the end of kindergarten, according to the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts. So the question is: What should parents do when their kids are infants, toddlers, or preschoolers to help them meet that expectation? When should letter instruction begin? How should it progress as children grow?

If books and reading aloud are a part of your family life beginning in your child’s infancy, your child may begin to gain awareness of printed letters before their second birthday. For example, the Texas Infant, Toddler, and Three-Year-Old Early Learning Guidelines state that toddlers (18-36 months old) might recognize some letters with help, such as their own first initial.

“Help” is an adult drawing attention to the child’s name, for example, showing a monogrammed blanket and saying “Z says /z/. Z-O-R-A says Zora,” as they point to each letter in turn. Helping your child make the connection that a printed shape corresponds with a particular sound can be just as simple as repeating short sentences like that now and then—again and again over the days, weeks, and months of early childhood.

After three years old, kids’ letter-learning capacity noticeably expands. Between 36 and 48 months old, children might identify some letters, know the sounds some of them make, write letter-like forms, and even grasp that letters combine to make words, the Texas guidelines say. Some research suggests that three-year-olds can learn as much about the alphabet as four-year-olds. And about half of four-year-olds recognize their own first initial and can name some printed letters. Of course, fulfilling that potential depends on the visual experiences with print, and conversations around print, that young children have with the adults in their lives. So ramp up your letter teaching when your child is about three.

Formal letter instruction typically accelerates in the preschool and pre-K years. But the federal and state standards that early educators use to guide instruction vary widely in terms of how many letters they say kids need to know and by when. For example, South Dakota’s benchmarks expect that an older preschooler (45 to 60+ months) can “recognize and name at least half of both upper and lowercase letters of the alphabet.” In Texas benchmarks, by contrast, a child is considered on track at the end of preschool if they can “name at least 20 upper and at least 20 lowercase letters in the language of instruction.”

I say, aim to give your child rich lessons in letter names before kindergarten, because you don’t know which letters your particular child will pick up right away and which will take them more time to learn. Your child may even master them all, paving the way for more advanced literacy lessons come kindergarten.

Is it pushing kids too far, too fast to teach them the ABCs so young?

No. The timing of letter-learning matters because the number of letter names kids know at kindergarten entry predicts their later success in reading and spelling. And that’s independent of the child’s age, socioeconomic status, IQ, and other early literacy skills, according to the National Early Literacy Panel.

Evidence supports aiming for kids to learn 18 uppercase letter names and 15 lowercase letter names by kindergarten, say researchers who study the relationship between preschool learning and later academic outcomes. In other words, kids are fully capable of knowing that many letters at kindergarten entry (with our help), and those who do are more likely to succeed in the classroom.

Some parents may object to directly teaching letters to three-year-olds—and to the notion that kids should know the whole alphabet by the end of kindergarten—on the grounds that they learned their letters later in life, and they read fine.

The problem with that thinking is that, rightly or wrongly, U.S. elementary-school standards are much higher today. And children who don’t know enough letters when they start kindergarten are likely to struggle to grasp classroom instruction, fall further behind peers, and experience feelings of anxiety and inadequacy.

Other parents point to the reading success of students taught in traditions that don’t even commence reading instruction until kids are seven years old—such as in Waldorf schools or in Finland. But we don’t know how much letter experience those children receive outside of school, and not teaching your child letters before kindergarten is ill-advised for parents who plan to enroll kids in traditional U.S. schools that teach reading sooner.

Letters are the building blocks of the words that kids must learn to read, and in most U.S. schools, letter names are the very “language of instruction,” researchers have observed. Sit in on a typical kindergarten class and at some point you’re likely to hear phrases such as the following, they note:

- “How do you spell cat? C-A-T.”

- “What’s the first letter of that word? A!”

- “What letter makes the /m/ sound? That’s right, M makes the /m/ sound.”

To make sense of questions like those above, students in traditional U.S. kindergarten classrooms need to know a good deal of letter names and have a sense of the function letters serve in words. Children who don’t know letter names can’t engage in the crucial conversations about reading and writing that they’re meant to learn from.

The main reason for U.S. parents to build alphabetic knowledge early isn’t that it’s impossible for kids to learn it later, but that our current system of education offers insufficient support for kids on that path. Most U.S. schools simply are not equipped to meet kids where they are. They’re set up to teach particular content at particular grade levels, and if your child isn’t there—good luck. Moreover, as children advance through the grades, their access to foundational reading instruction and effective intervention declines.

Simply put, parents need to prepare their children to thrive in the system they’ll be enrolling in. If your child is going to be traditionally schooled in the U.S., they need to be ready to navigate the customs, curriculum, and expectations found there. The good news is that any caregiver with even basic literacy, few to no materials, and just minutes a day can get them ready—with the right knowledge and approach.

Should you teach letter names first or should you teach letter sounds first?

It’s fine to start by teaching letter names, as most U.S. parents do, or by teaching letter sounds first, as most UK parents do. But for simplicity’s sake, I recommend teaching them together. Kids ultimately need to know both, and research shows that teaching letter names and sounds at the same time doesn’t confuse kids or over-burden their memory.

Letter names give young children the labels they need to make the different manifestations of a letter stick together in their memory—upper- or lowercase, print or cursive, one font or another.

And because many letter names bear some resemblance to their letter sounds (B says /b/, for example), little ones who have learned letter names have a tool for grasping and remembering the letter sounds they must learn in order to read.

When we talk about learning letter sounds, it’s important to note that there are really two things kids must grasp to know the sounds of the alphabet. The first is just learning to discern the individual speech sounds we hear in words (this ability is called phonemic awareness). The second is learning that letters represent those sounds. It’s a watershed moment when kids grasp the connection between printed letters and the sounds that make up words (known as the alphabetic principle). Suddenly, they are ready to start sounding out words in print.

Fun fact: There’s also evidence from research that the hand movement involved in writing letters is correlated with letter-naming fluency and solidifies letter-sound matches. That means all of your letter work is interrelated and mutually reinforcing.

How do I know if my child is on track with learning the alphabet?

You can do an informal assessment of your child’s letter-name knowledge by writing uppercase and lowercase letters on separate index cards, showing them in a random order, and asking your child to name them. Then record the date and whether they responded correctly or not on the back of each card. If the response surprises you or is noteworthy in some respect, jot that down on the back of the card as well.

These casual notes about what your child knows, and when, will prove invaluable as they move towards reading. This kind of simple assessment is the basic method that many literacy researchers use.

Just keep in mind that you are a parent and not an official testing agency with rigid protocols to follow, so it’s best to keep your letter assessments light and fun as well. You don’t have to assess all 26 letters in one sitting. Try doing a few at a time. Then do a few different ones the next week. If your child seems to enjoy the exercise, though, go ahead and run through as many as they have the interest and patience for.

If you have concerns about your child’s progress or just want a second opinion, it’s also a great idea to inquire about an “emergent literacy screening” when your child is preschool- aged. Check with your local school system or municipality for details. For example, in Wisconsin, where I live, the state requires each school district and charter school to assess all early-elementaryeach students for reading readiness annually, starting at four years old. Moreover, by law, the district must share the results of the reading readiness assessment with parents and provide interventions or remedial services if the child is at risk of reading difficulty.

It’s also important to get help if you’re not sure your child is progressing as they should. Many children who may seem to be lagging can make great strides with a bit of outside instruction. Some don’t, though, and it’s important to figure out early if your child is at risk for potential reading difficulty and needs more intensive early intervention.

Now that you know what your child needs to learn about letters and when, check out our literacy activities for hands-on ways to add alphabet play to your day.

And the fact is teaching letters should be every parent’s aim, and staying on task with it is a game-changer. That’s because relying on school alone to teach kids their ABCs is a losing strategy. One study of 81 preschool classrooms found the teachers spent an average of just 2.77 minutes a day teaching letters. The rest of the time they focused on other important self-care, social-emotional, and pre-academic skills. Imagine how easily you could double that time at home and target the lessons to your child’s level.

What questions do you have about teaching your child the ABCs? Let us know on our socials or email hello@mayasmart.com. We’ll respond with research-based answers and resources.