Think back over your last few months of spending. What were the big-ticket items or experiences that you purchased for your child? If you were to judge yourself on where you invested dollars on their behalf, what would those expenses say about your priorities?

Sports, travel, and clothing topped my list of spending for my daughter this summer. She moved to a new soccer team, which required buying all-new everything: socks, shorts, four different jerseys, a backpack, outer gear for all weather, and the list goes on and on. As luck would have it, the one thing the team didn’t require—new footwear—made its way into our shopping cart anyway, because her old cleats no longer fit.

I’m talking hundreds and hundreds of dollars, far more than I spent on education during the same time frame. Do I value soccer over education? No. Does my spending look like it? Yes.

While there’s not an exact correlation between what we spend and what we value, I do believe that our visible spending sends kids strong messages about our priorities. How we spend says more than we intend.

Reading on the Road

So to tip the scales a bit in reading’s favor, I decided to put a lit-rich trip into the mix. If we can travel to Missouri and Arizona for soccer, I thought, why not go to our nation’s capital for reading? The Planet Word Museum and the National Book Festival had long topped my list of literary destinations to check out, so I brought my mom and my daughter along to make a weekend of it.

The Planet Word Museum was well worth the time and travel. Educator and philanthropist Ann Friedman’s founding vision for transforming the historic building has been beautifully realized, down to minute details like language symbols embedded in flooring and elevator interiors that look like library shelves. Every inch of the space exudes intention and enthusiasm for the human experience of language.

Most remarkable for a museum dedicated to words, it resists the urge to overwhelm visitors with print. It offers immersive, sensory, memorable experiences with language, using movement, light, and sound to capture visitors’ attention. It leaves space for guests to create our own meaning from what we consume, versus having it spoon-fed to us through the long placard descriptions typical of museums.

Everything at Planet Word is engaging, but here are a few of our favorites to give you a taste of the experience.

Global Voices

In your excitement to enter the museum, don’t miss the courtyard’s gorgeous, interactive art. Experiential and evocative, a towering aluminum sculpture, called Speaking Willow by visual artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, commands the space. Ivy creeps up its trunk and bell-shaped LED lights and speakers dangle from its branches.

When visitors pass under, it murmurs words from 364 different languages, representing the languages spoken by more than 99% of the world’s people. The speech —general statements about the various languages and cultures represented—isn’t meant to be parsed. Rather, let the words wash over you and inspire your sense of wonder at the richness, diversity, and interconnectedness of human communication.

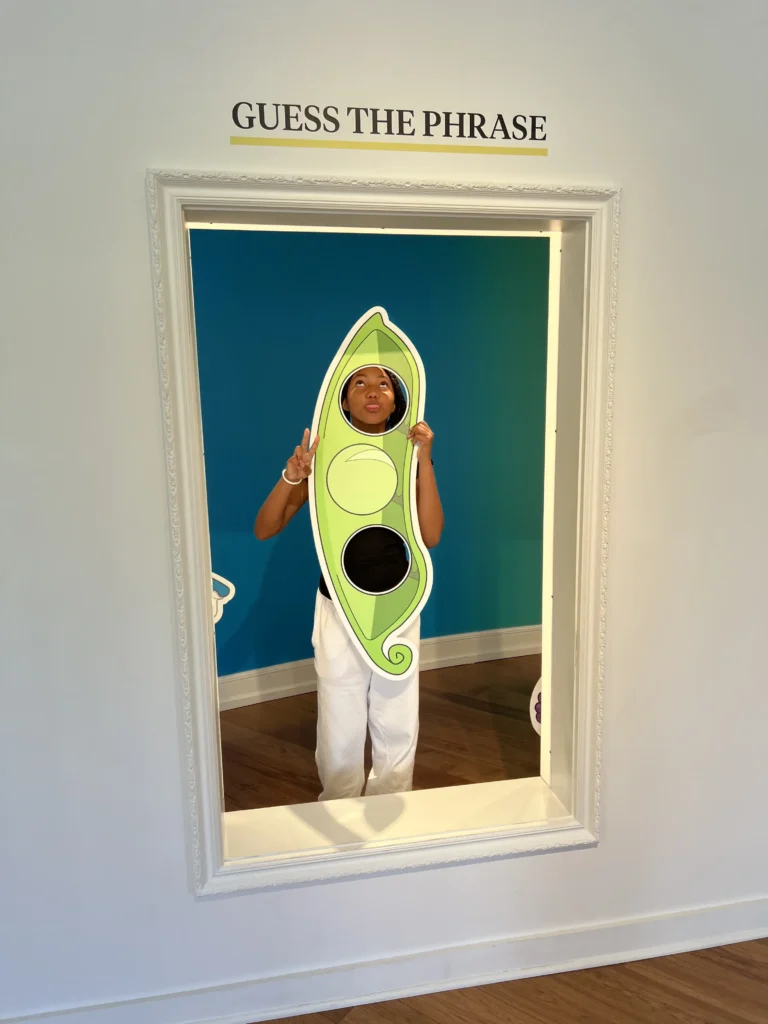

Iconic Idioms

The Joking Around exhibit gives visitors a shot at shouting out iconic idioms—if you can take a visual hint from the provided props. We caught on to some pretty quickly, like “in a pickle” and “two peas in a pod,” but others left us stumped… to this day. Go ahead, have at these word puzzles. Then visit Planet Word for more. This light-hearted, interactive exhibit gets kids (and adults) thinking about the playfulness and creativity of figurative language.

The Word Wall of All Word Walls

Kids may be familiar with classroom word walls, filled with high-frequency words or lesson-specific vocab. This is not that. Planet Word’s 22-foot-tall talking word wall tells the story of the English language, through video and illuminated words. Visitors play a role, too, using microphones to interact with the exhibit and help shape the narrative.

Native Speakers

The Spoken World exhibit showcases iPads arrayed around a globe of lights. The screens offer mini-lessons in languages from Icelandic to Wolof, which highlight the diversity of world languages for us, as well as the universality of communicating culture and community. We loved the chance to practice words in unfamiliar tongues and ponder the heritage and identities of the speakers, as well as our own.

Gifts of Gab

I love a good gift shop, and Present Perfect at Planet Word had it all—bookish socks, pins, puzzles, games, and even dishes digging into tricky words like they’re, their, and there. There were books for word nerds of all ages, from Spelling Bee savant Zaila Avant-Garde’s Words of Wonder from Z to A picture book to Joe Gillard’s The Little Book of Lost Words: Collywobbles, Snollygosters, and 86 Other Surprisingly Useful Terms Worth Resurrecting. If you’re on the hunt for a baby shower gift, I recommend this adorable onesie. It pairs perfectly with my book, Reading for Our Lives.

We tapped out after two hours at the museum, which means there’s still much, much more to explore. On our next visit, we’ll be sure to dine at Immigrant Food, tackle a word-puzzle case in Lexicon Lane, and dig into the “I’m Sold” advertising exhibit. And I’m sure we’ll pick up a few more SAT words in the photo booth, sponsored by the College Board.

Long story, short. We loved it. Five stars. We’re sold on the idea that Planet Word truly is “the museum where language comes alive.”

Summer break arrives, and with it, the familiar quest to keep kids reading during their time off from school. Many parents optimistically enroll children in summer reading programs, hoping it helps kids foster a love for books and learning. And to sweeten the pot, libraries tout rewards like coupons and gift certificates to entice kids to hit milestones—say, a certain number of books or minutes read.

As a child who loved to read, I know the appeal personally. I recall carrying a stack of books taller than myself to the checkout desk at my local library in preparation for their summer reading program. I’d scavenge the library, meticulously looking through each section, hoping to find interesting books that were short enough to finish in time to receive a prize.

But now I wonder: What comes first, the love of reading or the enticement of a reward? Do rewards really help kids fall in love with books, or are they just icing on the cake for kids who already enjoy reading?

Let’s look at the arguments for and against summer reading rewards programs—and the story of one library that ditched them in favor of building up kids’ basic reading skills in a county where low literacy is endemic.

The Case for Summer Reading Rewards

Conventional wisdom says incentives get kids into the library, encourage them to seek out books they enjoy, and get them reading more. A whopping 97% of public libraries nationwide offer reward-based reading programs, doling out everything from stickers, stuffed animals, and temporary tattoos to free books, coupons, and tablets. As one librarian noted, kids may come for the prizes but then “leave reading for their own sake.”

Surveys of and interviews with middle schoolers who participated in summer reading programs and their parents suggest that the effectiveness of prizes is a mixed bag: a combination of what’s called “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” motivation.

Essentially, “intrinsic” motivation is when you want to do something for the sense of satisfaction you get from doing it. In this case, that would be reading for the love of reading. “Extrinsic” motivation is when you want to do something because you’ll get some kind of compensation or outside approval for doing it. Here, that would be reading to get a reward.

Popular thinking is that intrinsic motivation is more powerful, but research suggests that people aren’t driven completely by intrinsic motivation or completely by extrinsic motivation, but rather by a complex mix.

Indeed, the surveys showed that some kids who already enjoyed reading appreciated program perks as nice add-on incentives and said they read more than they might have otherwise to meet program targets. Others felt the content of the prize itself was less compelling than the sense of accomplishment they gained from doing the reading required to earn it.

Most of the parents surveyed felt that their kids read more, improved their reading skills, and gained reading confidence as a result of the summer reading rewards programs.

The Case for Ditching Reading Rewards

But not everyone is convinced that such summer rewards programs meaningfully fuel a love for reading—or even that administering them is a good use of librarians’ limited time.

Veteran children’s librarian Anne Kissinger believes libraries should focus on directly helping kids gain reading skills (which many lack, according to the numbers) instead of celebrating pages turned over the summer. In fact, she successfully lobbied for her library system to abandon summer rewards programs altogether.

For years, she says librarians at the Wauwatosa Public Library where she worked spent most summer days stamping coupons for participants in their reading rewards program. In summer 2017 alone, the library system distributed 3,000 rewards.

But at the height of this apparent success of the summer reading program, she worried that the library had evolved into a “clearinghouse” for promotional goods instead of a bastion of reading skill and interest. “They’re not reading for their own enjoyment,” she observed of kids participating. “They’re reading to fill in our logs or meet our requirements.”

With her branch located in a county where 25% of adults read at or below the lowest literacy level, peddling extrinsic motivation at that scale felt to her like shirking responsibility. Faced with the choice of sticking to the status quo or championing a deeper commitment to reading, she advocated to free librarians’ time up from stamping coupons and direct it toward better equipping parents to help their kids learn to read in the first place.

Reading specialist and Wauwatosa library patron Christine Reinders noticed the change in what the library offered physically—and culturally. It had always been a place where parents could find material to read to their children, but now it was becoming a space where parents could support their kids to read to themselves. For example, it was offering more books with simple words that kids can sound out along with more support for parents teaching their children to read.

“‘[Wauwatosa] is a really special place, because they had a library and a children’s librarian who recognized this need” to cultivate basic literacy, Reinders said. “The library was filled with all these wonderful books, but many were not accessible because kids were just learning to read. Now, we have those beginning readers to help them establish that solid foundation to become proficient readers and writers.”

Lessons for Parents From the Reading Rewards Debate

Ultimately, rewards may get some kids in the library and reading more in the short term, but parents would do well to attend to the longer term and intrinsic motivation, too. That’s the kind of motivation that stems from kids learning to read with enough skill, fluency, and understanding to enjoy it.

And libraries like Wauwatosa’s can be great partners in that pursuit when they offer resources for parents about fostering reading skills, as well as simple early reading material for kids.

After all, reading motivation is no simple black-and-white matter. Once we can read, we do it for many reasons: interest in the story, curiosity about the topic, the satisfaction of learning or getting to “the end,” the joy of personal choice, the prospect of a prize. We’re driven by a messy mix of reasons and inspirations. Parents and others hoping to encourage kids to read, or read more, may be best served by leveraging the gamut of motivations.

Confession time: For someone who preaches deep family and community involvement in children’s education, I’m not a constant presence at my daughter’s school. I couldn’t pick many of her teachers out of a lineup, and I rarely sign up for parent-teacher conferences.

In my defense, they’re virtual and so short that by the time we exchange pleasantries, they’re practically over. My emails to the school are mostly logistical: “She’ll miss class for a family commitment/soccer tournament/orthodontist appointment, sorry!” And you know what? I’m okay with that.

The truth is, your involvement with your child’s school will naturally ebb and flow based on your circumstances, interests, and—most importantly—your child’s needs. And that’s exactly as it should be.

When my daughter was younger, I was all in. She attended a public Montessori school for a brief time, and I wore every hat: school board member, reading buddy, field trip chaperone, you name it.

I felt a deep obligation to advocate for all children in a school serving many under-resourced families. Plus, I wanted to make sure she was getting the foundational skills she needed for long-term success. But as she has grown and her needs have changed, so has my school involvement.

Now that she’s a teenager, I focus more on empowering her to take responsibility for her education. I want her to check her own grades, follow up with her teachers, and learn to communicate effectively—life skills as much as academic ones. My role now is backup and coach.

I’m still deeply engaged, but my involvement looks different: daily conversations directly with her, gentle nudges, and teaching moments about things like the perils of group projects, email etiquette with teachers, and how to ask for help.

So, what’s the takeaway for you?

Parental school involvement and supporting your child’s education doesn’t have to look one way. It doesn’t have to mean signing up for every conference, attending every event, or leading the PTA.

It just needs to reflect your family’s unique circumstances and your child’s needs at the moment. And here’s the good news. You get to decide what that looks like.

Three Simple Steps to Meaningful Engagement

- Stay Aware

Keep a pulse on how your child is doing developmentally and academically. If they’re in preschool, know the milestones typical for kids their age. For school-aged kids, familiarize yourself with grade-level expectations and where your child stands. If something feels off, ask questions. Teachers and administrators are there to help. - Reflect on the Data

Look at report cards, state assessment scores, and other information the school provides about your child’s learning. Even a quick review can give you insights. If teachers raise concerns—whether academic or behavioral—engage in constructive dialogue and work together to find solutions. - Seek Support When Needed

If challenges arise—and they will at some point, about something—explore resources both within and beyond the school. Schools often offer tutoring, reading buddies, or other support. Libraries, community organizations, and even your personal network can be incredible allies in your child’s learning journey, too.

Above all, give yourself permission to change your approach and intensity as you and your child grow. Some seasons of life will call for all-hands-on-deck engagement. Others may let you step back. Both are okay.

Set Your Own Standard

Here’s the bottom line: Thoughtfully decide how you want to show up for your child, and then show up that way. Whether you’re the board member parent, the email-only parent, or somewhere in between, your ultimate goal is the same: to meet your child’s needs and support their development. Sometimes for busy parents that means leaning on others, too—a partner, grandparent, or someone else who can fill in when you can’t.

You don’t have to do it all. Nurturing a child’s development is its own kind of group project.

Get Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six

Learn how to foster your child’s pre-reading and reading skills easily, affordably, and playfully in the time you’re already spending together.

Get Reading for Our Lives

This year marks the 10th anniversary of my turn as The Richmond Christmas Mother, a community fundraising campaign I led that raised more than $325,000 to make the holidays a little brighter for Central Virginia families in need. It was the 80th anniversary of the Christmas Mother Fund, and I was the youngest woman—and first black woman—to helm the effort. I quipped at the time that for the last several years the committee had selected Christmas Grandmothers. (Daphne Maxwell Reid, the original Aunt Viv from The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, followed me in the role in 2018.)

In retrospect, that campaign signaled a turning point—not just for the fund, but for me personally. It marked a pivotal early step in my personal transformation from community volunteer and book cheerleader to early literacy leader and parent engagement pro. The campaign added “child literacy advocate” to my name in news headlines for the first time, and it stuck. In the years since, I’ve added new titles like “author” and “parent educator” to the mix, as I’ve sharpened my understanding of what it takes to really move the needle on reading achievement.

The Christmas Mother Fund historically directed most of its support to the Salvation Army’s Christmas assistance programs. But during my tenure, we expanded its impact by launching a competitive grant project in partnership with the Community Foundation. We interpreted “Christmas” broadly to extend all the way from Thanksgiving to New Year’s and aimed to reach into 80 different pockets of the community through local organizations big and small. This allowed us to support incredible work, such as providing home-cooked meals to homebound seniors and disabled people and bringing joy to kids battling cancer.

While I did the usual hustling—placing calls, talking with media, meeting with local businesses, and presenting to civic organizations—I also put my own spin on the campaign. I donated copies of Each Kindness and other Jacquelyn Woodson books to local children at schools and child care centers. By the season’s end, I’d distributed more than 1,000 books. My Christmas Parade float, too, reflected my passion for literacy: I decked out a trolley in homage to Ezra Jack Keats’s classic picture book The Snowy Day. The marvel of art, craft, and engineering on wheels was brought to life by a dedicated team of volunteers. (Yes, we hung countless hand-cut snowflakes from the trolley windows to ensure a white Christmas.) All in the hopes of inspiring reading, encouraging parents to read to their children, and getting families to give books for Christmas instead of only toys.

Along the Dominion Energy Christmas Parade route, I tossed stuffed dolls of Peter, the main character of The Snowy Day, into the crowd. (Throwing board books into the air felt too risky.) I was joined by author friends Meg Medina, Gigi Amateau, Robin Farmer, and Stacy Hawkins Adams. At the time, I thought I might follow them into publishing fiction. Instead, I walked a different path, writing for parents and encouraging families to raise readers.

This wasn’t my first foray into advocacy. Previously, I’d launched a campaign to raise funds and awareness for Friends Association for Children, an early childhood development center that I adored and that I later highlighted in the conclusion of Reading for Our Lives. But my Christmas mother campaign gave me a platform to articulate what I now see as my core conviction: if we want to address society’s most entrenched challenges, we need to invest in children’s early education and literacy.

Looking back at a 2014 interview with Cheryl Miller on Virginia This Morning, I’m reminded of how long and deeply I’ve held this belief. All those years ago I said, “I’m a really big advocate for early childhood education programs and literacy programs for our children. I think as a community, we can invest more in children earlier and prevent a lot of the problems that many social-service organizations are grappling with as the children age.”

Some things never change! Ten years in the game and I say some version of this daily. Only now, I have the privilege of taking stages nationwide to spread the message. In 2024 alone, I addressed thousands of early childhood educators, K-12 teachers, librarians, interventionists, and parent educators in states as far-flung as Wisconsin, Louisiana, Iowa, Ohio, Maryland, Florida, and Idaho.

The Richmond Christmas Mother campaign wasn’t just a fundraiser. It was a turning point, a launchpad, and a testament to the power of a community coming together to create change. It’s been 10 years, but the lessons I learned and the momentum it sparked continue to shape the work I do today.

Get Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six

Learn how to foster your child’s pre-reading and reading skills easily, affordably, and playfully in the time you’re already spending together.

Get Reading for Our Lives

Literacy First, an Austin-based high-impact tutoring program, kicked off its 30th anniversary celebrations in a meaningful way: with a virtual book club discussion of my book, Reading for Our Lives.

Rather than just retrospective fanfare, the organization chose to ponder its mission by engaging staff, board members, district partners, and the broader community in a thoughtful dialogue about work outside of its current scope. The topic: engaging with parents of kids before they arrive in school. This choice underscores Literacy First’s commitment to continuous learning and using collaboration to drive change.

Reading for Our Lives Book Discussion

It was a pleasure to join the conversation with readers who had already engaged with the book. Their questions showed real curiosity and thought, diving into the nuances of my writing process: Why that title? How did I decide which histories and voices to feature? We also explored practical strategies for supporting young readers—tools that anyone, whether a parent, teacher, or community member, could use.

The discussion took on some of today’s most pressing literacy topics, including how to embrace multilingualism as an asset to literacy development. Another topic we addressed was the role organizations like Literacy First, along with partners such as BookSpring and school districts, can play in achieving literacy for all children.

Participants were eager to dig into early literacy milestones, reflecting on the need for schools to raise expectations around specific literacy skills like phonemic awareness and decoding. A recurring theme emerged: the challenge of communicating to parents and educators that just good enough isn’t good enough—early literacy skills matter deeply, and they set the foundation for future success.

We also tackled practical concerns. How can preschools recognize the importance of systematic instruction? What strategies work for families with neurodiverse children or late talkers who aren’t ready to jump into conversations but still want to build literacy skills? And finally, I was asked a fun yet intriguing question: Have you thought about starting a podcast? (My answer: Try me in 2026!)

Literacy First: The Gold Standard of Reading Tutors

For three decades, Literacy First has set the bar for reading intervention through its effective approach, inclusivity, and measurable impact. Serving students from kindergarten through second grade in both English and Spanish, the program will support 2,000 children this year—adding to the more than 30,000 students it has helped since its founding.

I’ve followed Literacy First since 2017, and I can attest that it’s the real deal. During my time in Austin, I had the opportunity to observe its tutor training sessions, attend a tutor swearing-in ceremony, visit schools to see tutors in action, and celebrate the program’s successes. Making it possible for well-trained tutors to intensively support kids’s reading development in English or Spanish for 30 minutes a day 5 days a week is as impactful as it is rare.

Two key lessons stood out during my Literacy First observations. First, focus and intensity matter. To be effective, educators need to engage with research, identify the exact skills students need, and deliver targeted instruction at a dosage high enough to move the needle. Second, tracking progress is essential. Literacy First not only holds itself accountable to results, but it also makes sure its efforts translate into measurable improvements for students.

A Reading Mission That Matters

I’ve seen firsthand how transformative qualified tutors can be. There’s simply no substitute for a focused, intentional effort to teach more people how to teach reading. Sadly, in too many settings, reading tutoring falls short—not due to lack of effort, but because of a lack of expertise and funding.

Children deserve better. They need programs like Literacy First that combine research-backed methods with a commitment to excellence and accountability.

After 30 years of remarkable impact, Literacy First remains a beacon of hope for students, families, and educators. Despite its age, I think it’s just getting started.

Get Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six

Learn how to foster your child’s pre-reading and reading skills easily, affordably, and playfully in the time you’re already spending together.

Get Reading for Our Lives

Newsflash:

All those beautiful children’s books you’ve been collecting?

They won’t help your child learn to read or love it unless you actually read them—regularly. Sharing books with kids gives them indelible experiences and positive emotions around reading that make them want to read on their own. Yet many parents focus on what they plan to read to their kids and neglect the urgent matter of assigning time to actually do it.

And it’s no wonder. Endless book reviews and recommendations (mine included!) feed our picture book cravings and tout books for every theme, holiday, or moment in your child’s life. The coverage journalists and influencers give to the content of books grows our libraries and Amazon wish lists, far outpacing reports on how to build strong family reading habits.

There’s a lot to keep us parents from reading to our kids daily—from a wavering motivation to read and competing priorities to busyness, fatigue, and more. Not to mention our kids’ moods, attention span, age, and interest level.

But I’m here to tell you that looking beyond bedtime and identifying multiple, recurring opportunities to read with your child will pay off big-time. Building these routines not only fosters better vocabulary and language skills for your little one, but also more quality time, bonding, and well-being for the whole family.

The Anatomy of Family Reading Culture

Let’s face it: Reading stories is important, but building reading culture is transformative. Culture requires depth and frequency, so families that weave multiple strands of reading into the fabric of their daily lives reap the greatest impact.

Each family’s reading culture is the product of a unique mix of resources, relationships, and rituals. Factors include the books and other reading material you have in your home, how you show up to share them, and how frequently you do so. All of these can nurture your kids’ reading attention, interest, and motivation.

A family living in a book desert, for example, might not have much reading material, but could read fewer texts more frequently and with great warmth and get good results nonetheless. By the same token, a family with more resources might fill a child’s room with kid-lit but never take the time to read or discuss the books together—coming up short on relationships and rituals. Luckily, regardless of your starting point, there are always opportunities to ramp up your book collection, book talk, and reading routines.

Of all these elements of reading culture, rituals are especially powerful, because they increase the dosage of the other two: reading material and relationships. Reading together daily—preferably multiple times a day—boosts your child’s exposure to the vocabulary and knowledge in a wide range of books, plus it increases your engagement and conversation. The benefits of consistency are so pronounced that I believe that when you choose to read to your child matters as much as what you choose to read.

Designing Reading Rituals

Ready to establish some reading rituals to ensure that the books you’ve been collecting get read and discussed? Here’s how:

Step One: Choose Your Moments

As I learned from behavior scientist BJ Fogg’s Tiny Habits method, timing is critical. Fogg recommends consciously tethering new habits you want to build to your most deeply entrenched existing routines. This makes it easier to remember and implement the new habits. That’s part of why bedtime story reading is such a common ritual for families, with 87% of more than 2,000 parents surveyed by Scholastic saying their read-alouds occurred at bedtime or naptime. Kids go to sleep (or at least get in bed) every night, so it’s less of a stretch to add reading into the mix of tucking them in.

Bedtime is far from the only consistent, daily event that you can anchor reading to, though. Pay attention to your time with your child and make a list of the daily habits, routines, and points of interaction you share. Do you wake them up? Prepare meals? Eat together? Drive them to daycare or other activities? List out all the recurring moments. Think of things you do before noon, afternoon, and in the evening, right before they go to bed, etc.

Step Two: Brainstorm Behaviors

With your existing patterns in mind, look for opportunities to make reading tag alongside those activities.

Can you open up a book of five-minute stories after you wake your little one? Turn on an audiobook after you fasten your seat belt in the car? Point out words and letters on signs, or comment on your morning reading, as you drive through your neighborhood?

The goal is to weave reading and literacy into your day via small actions, making new behaviors as inevitable as brushing your teeth or eating dinner. Think of “tiny” as something that can be done in 30 seconds or less or in 5 reps or less, e.g. reading a page of a book (not reading for an hour) or pointing out a word or letter (not a dozen).

This doesn’t mean that you can’t aim high, just that you’re focused on starting small and (importantly!) celebrating sooner.

Step Three: Celebrate Your Successes

As you try out new habits, remember to celebrate your wins. Parents don’t get enough credit, so give yourself a mental high-five every time you successfully incorporate reading into a new part of your day. You could also celebrate out loud and bring your little one in on the action. Give them a high five along with saying “we did it!” to share your enthusiasm with them and put an exclamation mark on the experience.

In the Tiny Habits method, celebrations are truly the key to making the new behaviors repeatable. When you give yourself a pat on the back, pump your fist, or engage in the celebration of your choice immediately after accomplishing the new habit, you reinforce that behavior. Your celebration’s positive vibes trigger a dopamine surge, wiring your brain to link your habit with those feel-good moments.

If, on the other hand, you follow the accomplishment by mentally beating yourself up for not reading more, or sooner, or better, you do the opposite—discourage yourself. So be your own cheerleader to best instill positive habits.

As Fogg puts it in the Tiny Habits book: “There is a direct connection between what you feel when you do a behavior and the likelihood that you will repeat the behavior in the future.”

That’s great news! It means that we can form new habits quickly, even if it doesn’t always feel that way. Contrary to popular belief, it’s not how many times you repeat a habit that makes it stick. It’s how positive your emotions connected to the habit are— and that’s something we can consciously impact.

Step Four: Tweak and Repeat

Start by experimenting with a few new reading habits at once, so you can compare and contrast results. Don’t feel pressured to nail the perfect routine immediately. Try different times and methods of incorporating reading and see what sticks. This is a design process. Observe what works, adapt when needed, and keep refining your approach.

Through it all, stay tuned in to your child. If they’re squirmy before meals, distracted during playtime, or tired at night, don’t push it—try other times and places. And if the books you’ve picked aren’t grabbing their attention, switch things up until you find some they love.

Remember, the most compelling picture book in the world won’t build a lasting reading habit on its own. You reading it regularly to your child will.

And a proven way to make that happen is the kind of purposeful behavior design described above, bolstered by positive emotions. So skip obsessing over finding the perfect books and focus on weaving reading throughout your busy days instead.

Where can toddlers collaborate with a Grammy-nominated cellist to create new music? At the Betty Brinn Children’s Museum in Milwaukee!

I participated in their Toddler Talkback program with Malik Johnson, the museum’s first Artist-in-Residence, and witnessed something remarkable: tiny hands helping create music alongside a musician who’s performed with Stevie Wonder and John Legend.

While that sounds like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, children’s museums create magic every day. This extraordinary collaboration illustrates what makes children’s museums so powerful for early development.

Each exhibit and experience is curated with little ones in mind, inviting them to explore, experiment, and make their own discoveries. Unlike screentime, these playful spaces spark fun, active, hands-on learning.

Why Museums Beat Screen Time Every Time

Special events aside, everything at children’s museums is designed at children’s eye level—within their reach and ready to be explored. The multisensory, accessible design of exhibits, along with the presence and voices of supportive adults, boosts kids’ experiences.

Multiple studies show that children’s museum visits foster measurable gains in:

- Language and social communication. Museum play boosts toddlers’ vocabulary, causal talk (like “if I do this, then that happens”), and storytelling skills. They also practice turn-taking, cooperation, and emotional regulation, especially when adults engage with them in supportive ways.

- Spatial cognition and exploration. Exhibits designed for hands-on engagement lead toddlers to explore more systematically, which sharpens problem-solving and spatial reasoning skills. That’s the foundation for everything from block-building to math concepts.

- Parent-child interaction. The research is clear: when parents join in with timely talk, support, or open-ended questions, toddlers gain even more. Adult involvement before or alongside a child’s exploration makes the learning stick.

Museums Build Vocabulary in Action

Here’s something many parents overlook: stepping out of your daily routine is one of the most powerful things you can do for your toddler’s vocabulary development.

While we might feel comfortable sticking to familiar activities at home, community experiences like Johnson’s cello sessions expose children to words, concepts, and ideas they might never encounter elsewhere.

During the session, toddlers heard words like cello and imagination—language that becomes the building blocks for future reading comprehension. When they see these words in books years later, they’ll have a reference point to understand them (not just sound them out) from that day they made music with a live musician.

Johnson’s artist residency culminated in a music video featuring the children’s snaps, claps, squeals, and dancing within their collaborative composition.

“I just took all of the magic that I remembered from all of the sessions, talkbacks and performances, and just put them in a song for you all to enjoy,” Malik said during the song’s release event. Imagine telling your child years later: You helped create this song with a Grammy-nominated musician.

The Real Return on Investment

Many museums offer free Community Access Days or library passes, but if possible, consider getting a membership. It’s not just about unlimited visits; it’s about making exploration a regular part of your child’s world. As Sarah McManus-Christie, the Betty Brinn Museum’s Education Director, puts it: “One of the museum’s values is to make memories that last.”

The song the children created captures this perfectly, with lyrics about imagination, reaching for stars, and being surrounded by friends at Betty Brinn. It’s a reminder that the most powerful learning happens when curiosity meets community.

Your toddler’s future literacy skills are being shaped right now—not just by the books you read at home, but by every new experience, conversation, and vocabulary word they encounter.

To make the most of your next children’s museum visit:

- Follow your child’s lead. Let them explore what interests them and then talk to them about it. Use rich, descriptive language about what they’re seeing, touching, and doing.

- Ask open-ended questions. Try: What do you think that does? or How does that sound?

- Talk about it afterward, too. Revisit the experience by recounting what you did together and listening to your child’s reflections, strengthening their memory and language.

To find a children’s museum near you, visit Findachildrensmuseum.org.

When your kid is desperate to spell a word—even if they type “Ueuuehh” for skateboard—that’s your golden teaching moment.

Case in point: a hilarious viral clip of a sharp five-year-old lecturing his mom on her unwillingness to download an app for him. “That’s not taking ownership,” he scolds. When she questions his understanding, he nails it: “It’s being responsibility.” He knows exactly what he means.

When Mom still says no, he takes matters into his own hands, typing a query in the app store: Ueuuehh. Does this say skateboard? he asks her. Not quite, buddy. But wow—what persistence, creativity, and focus on display. He can’t spell yet, but he’s thinking, questioning, problem-solving.

He’s locked in. He’s motivated. He wants to be able to type skateboard. (He doesn’t yet know that he can ask Siri and bypass writing altogether. Thank goodness!)

These are our teachable moments. This is when we can lean in and give a little print-focused literacy lesson. Reading means connecting sounds to print—what researchers call the alphabetic principle. To type skateboard, the child has to hear the /s/ sound, know it’s linked to a letter, and recall that letter is S. He won’t stumble onto that by chance. He needs grownups to point it out.

Here’s how: Point out letters to your child or write letters to show them. Trace the letters with your finger. Say their names. Call out the sounds. For example, you could say, “See this L? Long line, short line. It says /l/, like in Lucky Charms.” These light touches—on signs, cereal boxes, stoplights—help kids notice letters, recognize patterns, and link sounds to print.

These teachable moments happen naturally between the ages of about 3 and 6. The key is recognizing and seizing them. Keep it casual. Comment on a letter here and there as you go through daily life. If your child doesn’t seem interested, move on and try again later. Never let it become frustrating.

Research shows early mastery of these connections predicts later reading and spelling success. You don’t need fancy programs—just curiosity, patience, and 30 seconds a day. Today, pick one letter in your home, trace it with your child, and talk about its name, shape, and sound.

Get Reading for Our Lives: The Urgency of Early Literacy and the Action Plan to Help Your Child

Learn how to foster your child’s pre-reading and reading skills easily, affordably, and playfully in the time you’re already spending together.

Get Reading for Our Lives

It was my pleasure to join Nancy Redd on her Mompreneurs podcast recently to talk about my journey as a mom, entrepreneur, and author of Reading for Our Lives. Our conversation emphasized one simple truth I want every parent to know: we are our children’s first and best teachers. Long before our kids set foot in a classroom, our voices, conversations, and shared stories lay the foundation for their reading success.

There’s no magic bullet for literacy. Instead, what your child really needs is you—your voice and your attention, across the days and years. The good news is that you don’t need fancy toys or expensive programs. Talking with your child from infancy (even before they can respond) and as they grow builds their vocabulary and strengthens their brain. Reading picture books, asking questions, and giving your child time to think and reply can turn everyday moments into literacy lessons. These simple, consistent interactions add up to something powerful over time.

Another point I shared is that we parents must not underestimate our influence on our children’s literacy, which shapes their whole academic experience and beyond. Schools and teachers matter deeply, but their work rests on the groundwork parents build at home. Whether it’s five minutes of story time, a playful chat in the car, or a mini ABC lesson over breakfast, each little interaction contributes to your child’s growth.

A few more takeaways from our conversation:

- Knowledge and comprehension fuel literacy. Learning to sound out words is essential, but kids must also know what the words mean. Without rich conversation and exposure to different ideas and experiences, they’ll lack the context to make sense of what they read.

- Reading and writing still matter in the tech age. Artificial intelligence and tech tools may smooth over weakness in reading and writing, there’s no substitute for being able to think independently and communicate effectively. Ask your child: Do they want to be the person who’s reliant on these tools, or the person who shapes them?

- When it comes to screen time, parents set the pace. If we’re always on our phones, kids see screens as the norm. Even more, we lose valuable opportunities to talk, respond, teach, and read to our children. To help your child, start by modeling balance yourself.

Watch our full conversation below. And if you’d like to dive deeper into the science behind these ideas—plus get practical tips for weaving them into your family life—I share more in my book, Reading for Our Lives. It’s a guide for parents who want to raise strong, confident readers, right from day one.

Get Reading for Our Lives: The Urgency of Early Literacy and the Action Plan to Help Your Child

Learn how to foster your child’s pre-reading and reading skills easily, affordably, and playfully in the time you’re already spending together.

Get Reading for Our Lives

Every parent deserves to feel empowered as their child’s first teacher—and every child deserves the chance to thrive. That’s the driving force behind my book Reading for Our Lives and the community campaign I’ve built around it.

I wrote this book for parents raising readers, but I now have family-facing professionals in mind, too: nurses, early intervention specialists, child development educators, and social workers that parents turn to for guidance. These trusted advisors are uniquely positioned to share the book with families and help them act on its messages.

That’s why I created a way for generous readers to donate copies of Reading for Our Lives in bulk to organizations that already serve families. While some people are buying extra copies to give out at baby showers or pediatrician waiting rooms, I wanted to make it easier to give at scale—to get dozens or hundreds of books into programs with real reach.

The Impact in Action

Take Penfield Children’s Center in Milwaukee, which sends trained parent and child support professionals into homes to serve more than 1,600 children under age three in Milwaukee County alone. They already deliver children’s books, puzzles, and learning games to support early literacy. Now, they’ll be able to offer Reading for Our Lives to support parents too, giving them tools, inspiration, and confidence to lead their children’s learning from the start.

The book campaign will also deliver free books to families served by organizations including Penfield Children’s Center, Boys and Girls Club of Greater Milwaukee, and St. Francis Children’s Center.

How It Works

I’m thrilled to partner with Harmonic Harvest, a Milwaukee-based nonprofit whose mission of community empowerment aligns perfectly with Reading for Our Lives. This collaboration combines their expertise in community engagement with my focus on early literacy to create lasting change for families. When you donate to the Reading for Our Lives Book Fund, Harmonic Harvest handles the logistics—issuing tax receipts and working with local independent booksellers to distribute copies to partner organizations. Your dollars support families, community organizations, and neighborhood businesses all at once, creating impact that extends far beyond individual books.

This isn’t just about dropping off books and walking away. Every program that receives donated copies also gets access to live virtual Q&A calls with me, plus invitations to educational events and conversations. We’re not just building readers—we’re building a community of support around them.

Join the Movement

If you believe that every parent deserves support and every child deserves the chance to thrive, I invite you to contribute to the Reading for Our Lives Book Fund today. Together, we can put powerful books in the hands of families and the professionals who walk alongside them every day.

Let’s build something beautiful—one book, one conversation, one child at a time.