And did you know that dogs can be comforting, receptive audiences for children who need practice reading aloud? Furry friends make great listeners. They never interrupt with corrections like well-meaning parents and siblings sometimes do.

So the next time you do a read-aloud with your kids, invite your pets along to listen. Even if you don’t have a dog, you can still enjoy these picture books about puppies to warm your heart and teach your children about our furry friends—and maybe grab a stuffed puppy for your audience.

By Laila Weir

Who says Easter baskets have to be filled with all sweets? Lighten up on the sugar a bit and add some enrichment to your child’s Easter with a few fun and literacy-supporting Easter basket gifts. Below you’ll find links to tutorials for three Easter-themed recycled art projects. They’ll teach you to make totally free, eco-friendly, and easy DIY Easter basket stuffers!

What’s more, they’re educational: All three projects support oral language development and key early literacy skills that lead into important aspects of reading and writing.

You’ll learn to turn plastic Easter eggs into maracas and how to use them to develop your child’s rhyming skills. You’ll discover how to make old building blocks into storytelling dice that you can use to engage your child in spinning tall tales. And you’ll get instructions and printable templates for upgrading a paper lunch bag into an adorable bunny puppet, along with tips on how to use it in a fun literacy activity.

If you want another way to celebrate Easter with your little one and build their early literacy skills at the same time, read Chrysta Naron’s post on how to help your kid learn to read with a sight-word Easter hunt, too!

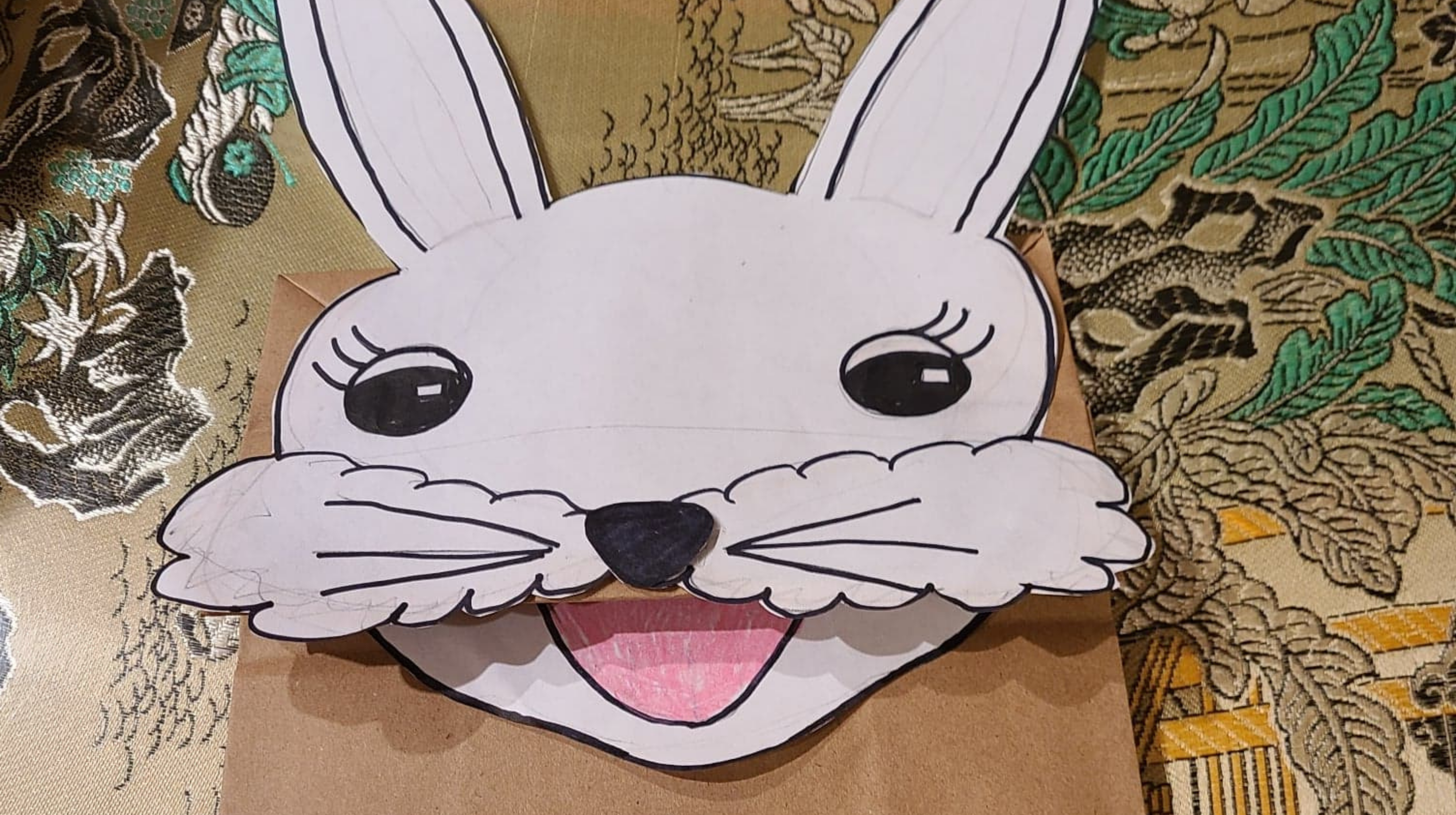

Easter Bunny Paper Bag Puppet

In this sweet Easter craft and activity, you’ll learn how to make an easy but adorable Rhyming Rabbit Easter Bunny puppet. Then you’ll help your child use their bunny to recite rhymes, from nursery rhymes and songs they know to beginner poems to come up with themselves. Using the bunny makes rhyming more fun, but it also has a deeper benefit: Reciting through a puppet can help children feel less self-conscious and free your budding poet or songster to get as lyrical or silly as they like.

Upcycled Plastic Easter Egg Maracas

In this super-easy, two-step craft, you’ll upcycle old plastic eggs into colorful musical instruments to welcome in the spring with a vibrant lyrical celebration. These cute maraca-style shakers are perfect for getting kids moving and learning! Check out the link for the instructions, plus detailed tips on how to use your child’s new shaker for maximum brain-building benefit.

Recycled Storytelling Dice

We love storytelling dice to get the ball rolling on inventing stories together with your child. This helps kids enrich their oral language, deepen their comprehension, expand their vocabularies, and develop key skills underpinning reading fluency. Plus, it’s a super fun game to play together! Sure, you could buy some of the many storytelling dice out there, but why not save the planet and your pocketbook by making your own from recycled materials, instead? In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to upcycle a couple of old building blocks into your own Easter-themed DIY storytelling dice.

By Chrysta Naron

Henry was a Go Fish shark. He was a legend among my Pre-K classes: The best Go Fish player you’d ever seen under the age of five. He played it every day in class. He played it to the point where none of the other kids wanted to play anymore. But Henry refused to play any other games.

It happened to be April—aka National Poetry Month—and our class was focusing on rhyming. So I decided to freshen up Go Fish and make it all about rhymes. The result was this awesome free rhyming game for kids that you can easily make at home. The children loved getting to help create the game, and so they were all eager to play. And as for Henry, it was close enough to the regular card game that he was happy, too. Everybody won!

Rhyming is a very important literacy skill that prepares kids for reading. Children love to be active participants in their learning, and they love it even more when grownups play with them. What’s more, this rhyming game is free and only takes about 10 minutes to make! This game ticks all the boxes, in my book.

Materials:

- Index cards (or sturdy paper/thin cardboard to cut up)

- Pencil, crayons, etc.

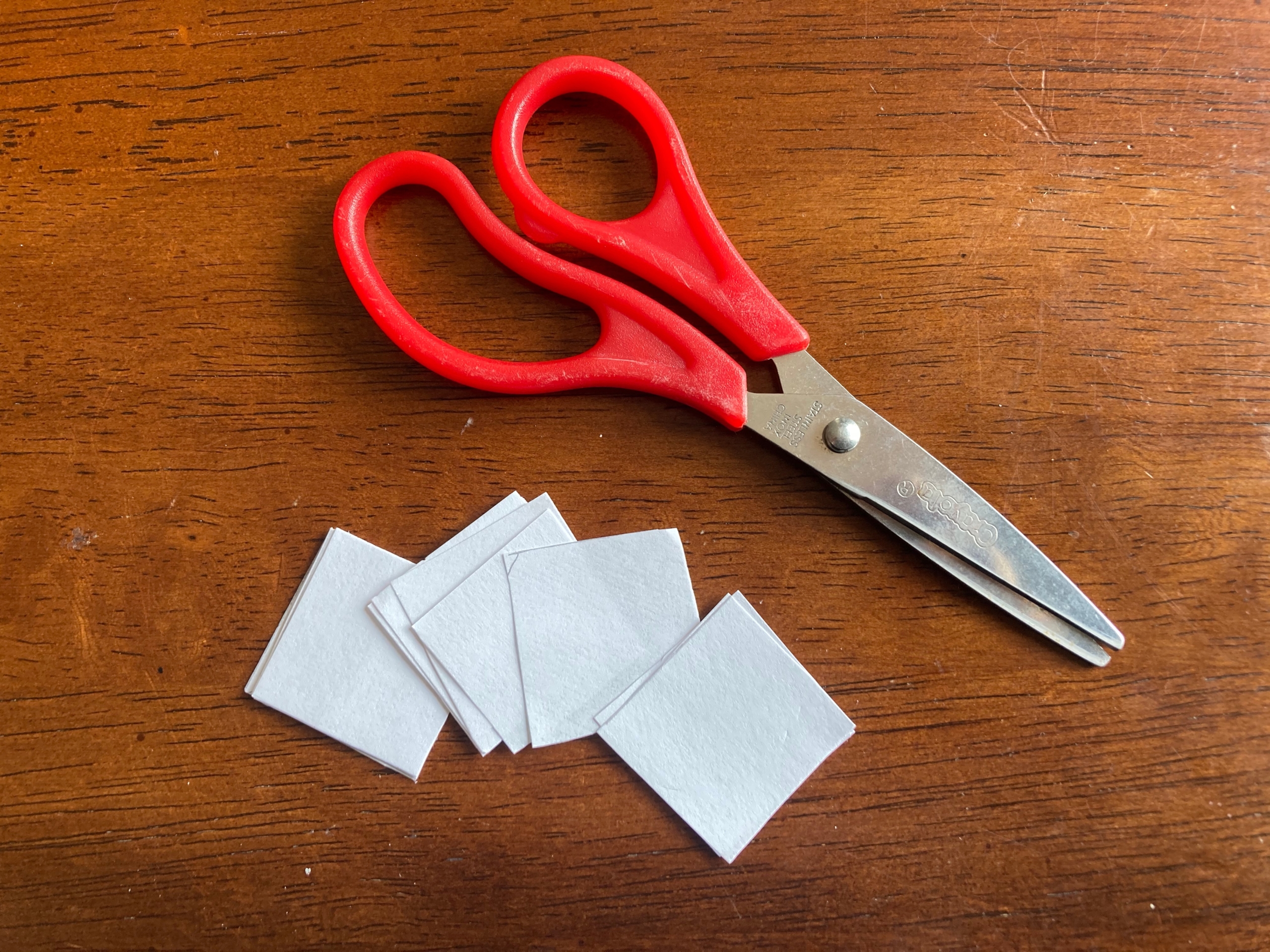

- Scissors, if using paper to cut up

Cost: It’s free! If you don’t have index cards on hand, just use cardstock or thick paper to cut into cards. You can even get creative and use thinner cardboard from boxes or containers that you would have recycled.

However, it’s well worth getting index cards on hand (they’re one of our must-have tools for teaching kids to read), and you can usually pick some up for under $2!

Step 1: Gather or cut out 40 index cards, and create 10 sets of 4 cards each.

Step 2: Each set of four cards will be its own rhyming family. With your child’s help, choose four rhyming words for each set, and write one on each card of the set. For example, one set might be “cat,” “sat,” “mat,” and “hat.” Another set might be “dog,” “log,” “frog,” and “bog.”

Tip: Write the words in crayon or pencil if your cards are on the thinner side, because markers may show through on the other side!

Step 3: After all the sets are complete, decorate with simple drawings of each item! This allows kids who aren’t reading yet to play. Rhyming is an important skill for pre-readers, so this step is key!

Tip: Make sure to only decorate the side with the word written on it. The backs should be blank, to avoid giving away matches during the game.

Step 4: Shuffle the cards and play Go Fish. The regular rules of seeking out matching pairs apply, but instead of asking for a number, ask for a rhyme. The person with the most sets of rhymes at the end wins!

As your child gains reading skills, you can modify the game. You can create sets that match in alliteration (i.e., their starting sounds match, like “cat” and “cup”) or make sets of two with homonyms (words that sound the same but have different meanings).

I’d love to know: How does your family make time to rhyme? Share your ideas!

I’ve always been proud of the fact that my daughter loves to drink water! Ava is a teenager now, but from the time she was young, I instilled in her the value of this essential resource and talked about how vital water is for not only our bodies, but also our planet. We all know that our bodies are largely made of water, but did you know that 71 percent of the Earth’s surface is water, as well?

March 22 is World Water Day, a day to celebrate and reflect on the importance this key molecule holds in our world. Here are 10 wonderful picture books to help you and your children learn about the world of water, and how crucial it is to keep this precious resource safe and abundant.

Which water picture book did your child enjoy the most? Let us know!

May is the time to celebrate and lift up the mothers and mother figures in our lives. But rather than just limiting our celebration to one day, let’s make a DIY Mother’s Day gift that lets them know how much we appreciate them every day.

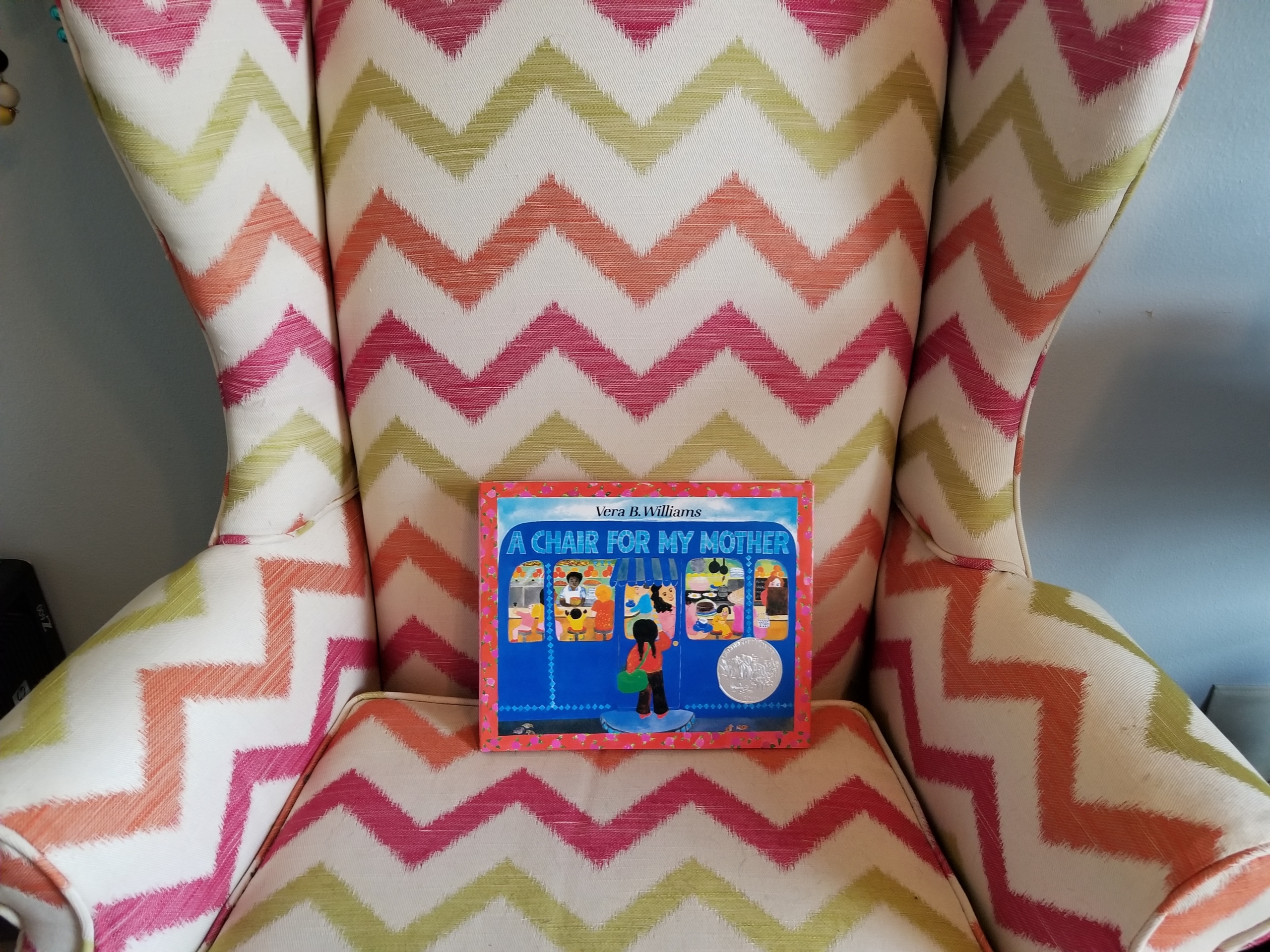

I love to kick off most kid projects with, you guessed it…a book! While there are many incredible picture books for this special day, I am particularly fond of A Chair For My Mother by Vera B. Williams. Most other Mother’s Day books focus on the emotion of love, the bond between parent and child, and simple acts like hugs and spending time together. This book is a unique narrative about a girl, mother, and grandmother who lost everything in a fire. It shows a community coming together to help people in a hard situation, and three generations of women dreaming and working together to support a loving mom. It’s a beautiful story with colorful illustrations that has a constant place in my home and classroom libraries.

In A Chair For My Mother, the characters save coins in a huge jar to one day buy a special chair for the mother to relax in when she comes home. That’s the inspiration for our Mother’s Day activity, but instead of putting coins in the jar, we’ll put love notes! Writing can be daunting for kids—they might love to read, but when asked to spell something on their own, they freeze. Through doing this activity together and giving it a personal purpose, writing becomes something a child wants to do.

Materials:

- A Chair for My Mother by Vera B. Williams

- A jar (clean it out and let dry completely before beginning)

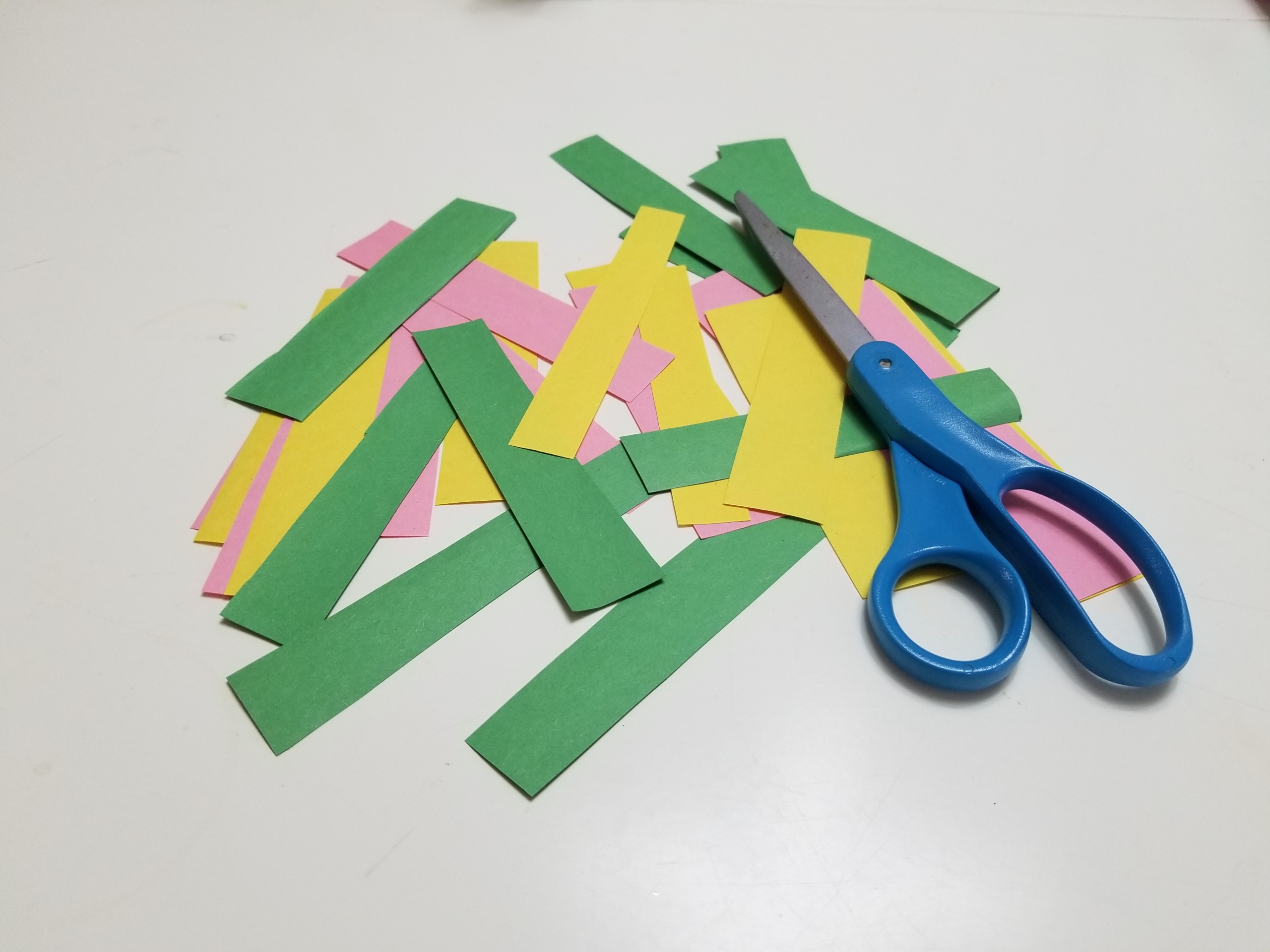

- Yellow, pink, and green paper (or any three colors!)

- Scissors

- Pencils, markers, and/or crayons

- Ribbon or twine

- Hole punch (optional)

Cost: Nothing, if you can get the book from your local library. Upcycle a cleaned-out food jar and reuse any scrap of ribbon you can find (you don’t need much). If you don’t have materials on hand, you should be able to get all the craft supplies for under $10.

Step 1: Find a favorite chair, cozy on up, and read aloud A Chair for My Mother to your little one!

Step 2: Cut out a bunch of strips of each paper color, making sure they’re wide enough to write on. I recommend cutting about 10 of each color, but any number is fine. It’s about your child’s comfort level with writing and the amount of time your family has to spend.

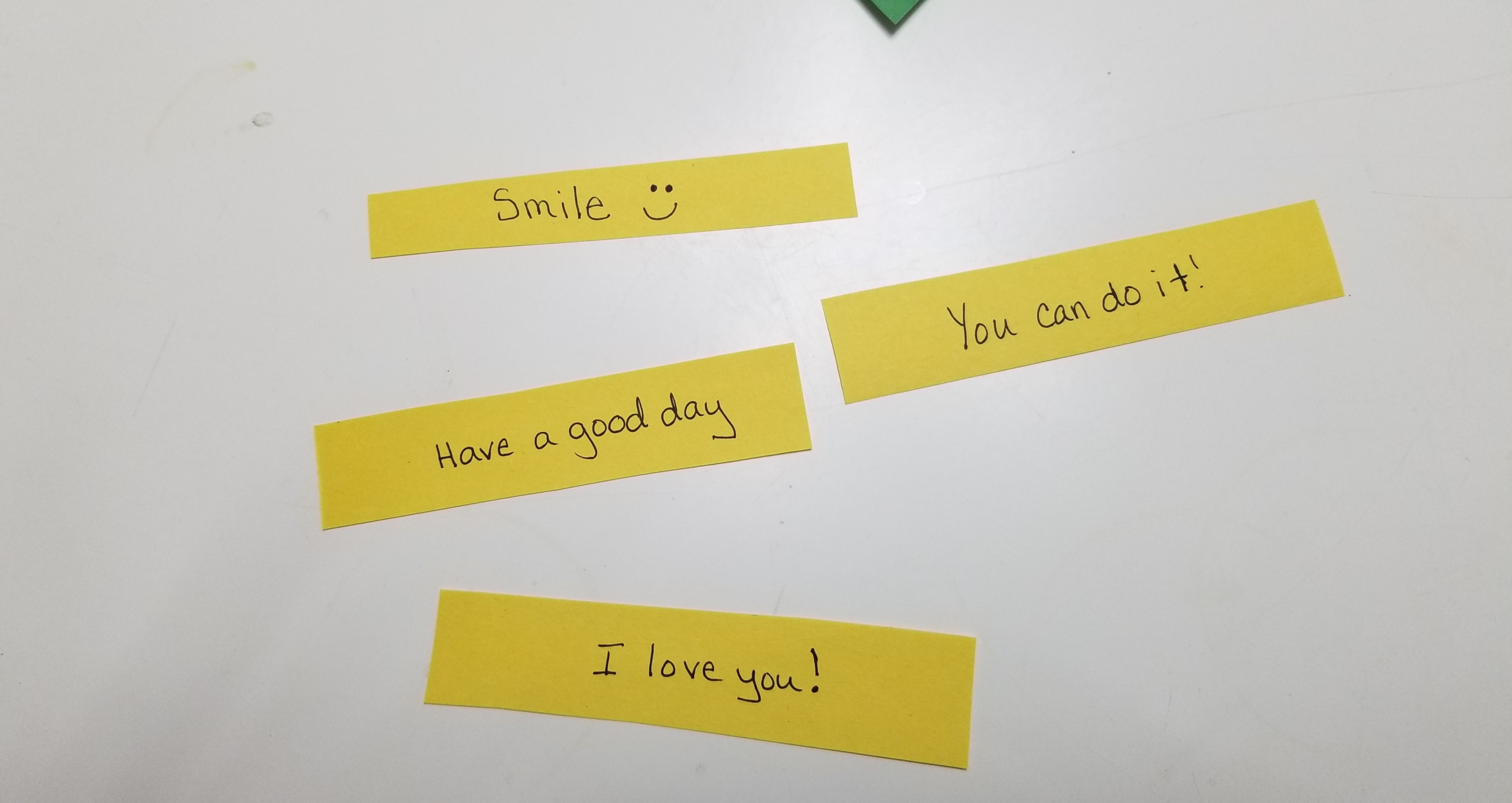

Step 3: On the yellow strips, help your child write encouragements. Encouragements are statements that can brighten someone’s day without being moment- or person-specific. Examples: “You’ve got this!” or “Have a great day!”

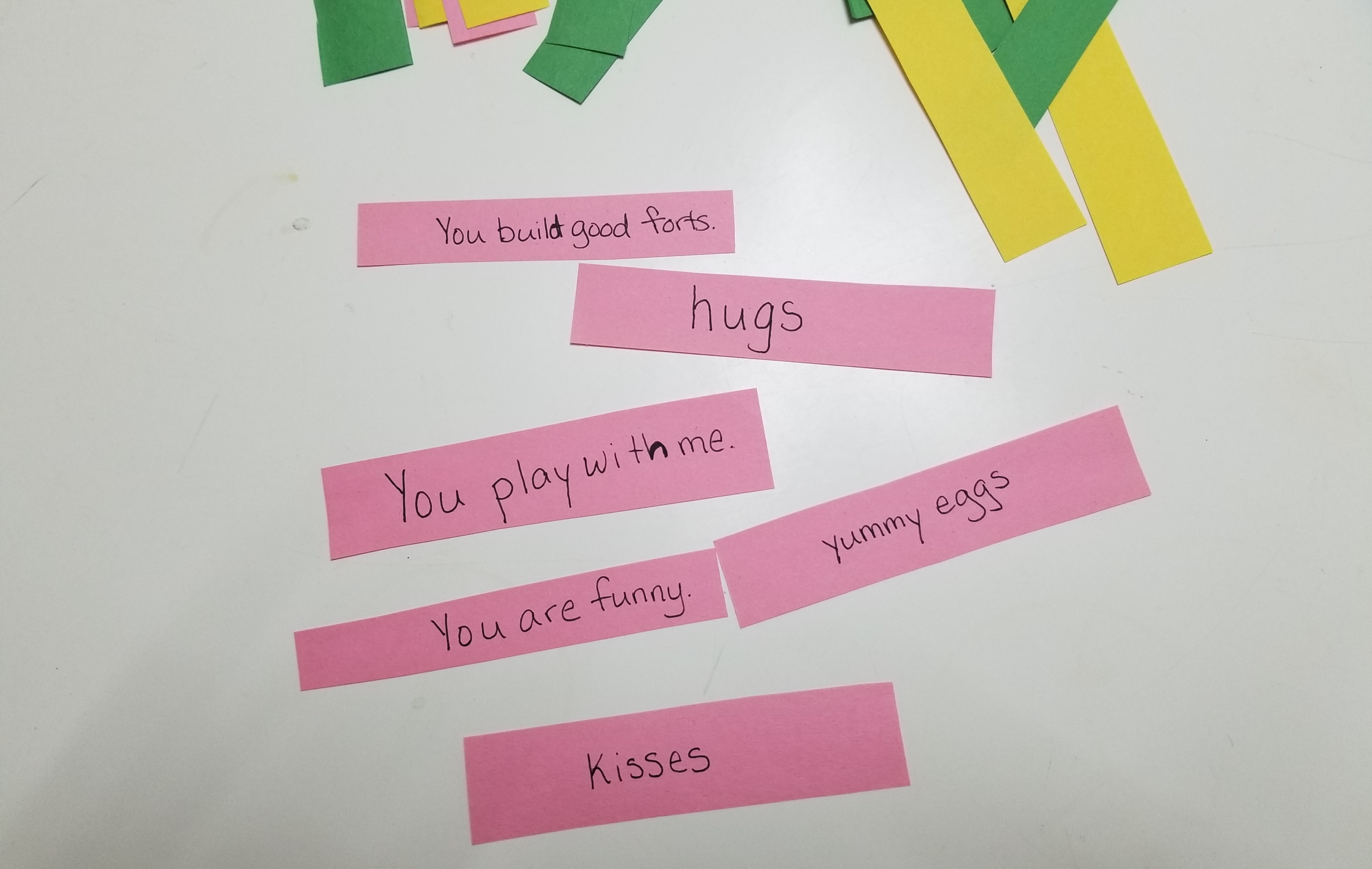

Step 4: On the pink strips, help your child write things they love about their mom or loved one. If your child is younger, it can be a single word like “hugs.” The older your child, the more complex their comments can be. Upgrade to “gives me hugs” or “Mom gives me the best hugs.” Adjust to your child’s skill level!

Step 5: On the green strips, let your child draw pictures. They can be silly scribbles, tiny rainbows, pictures of your family, or anything else they want. Let them express themselves however they please.

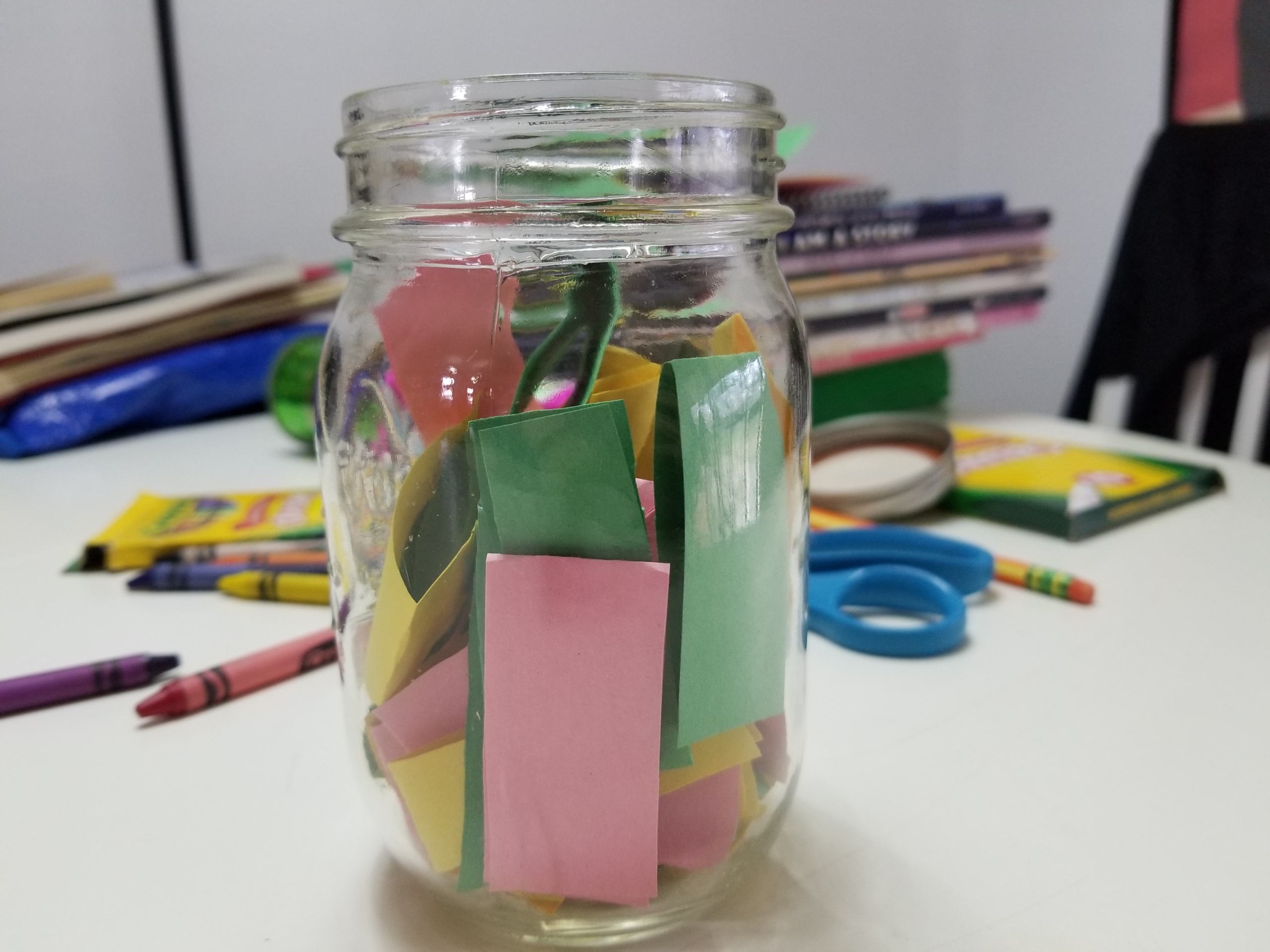

Step 6: Fold all of the notes in half and place them in the jar. Put on the lid.

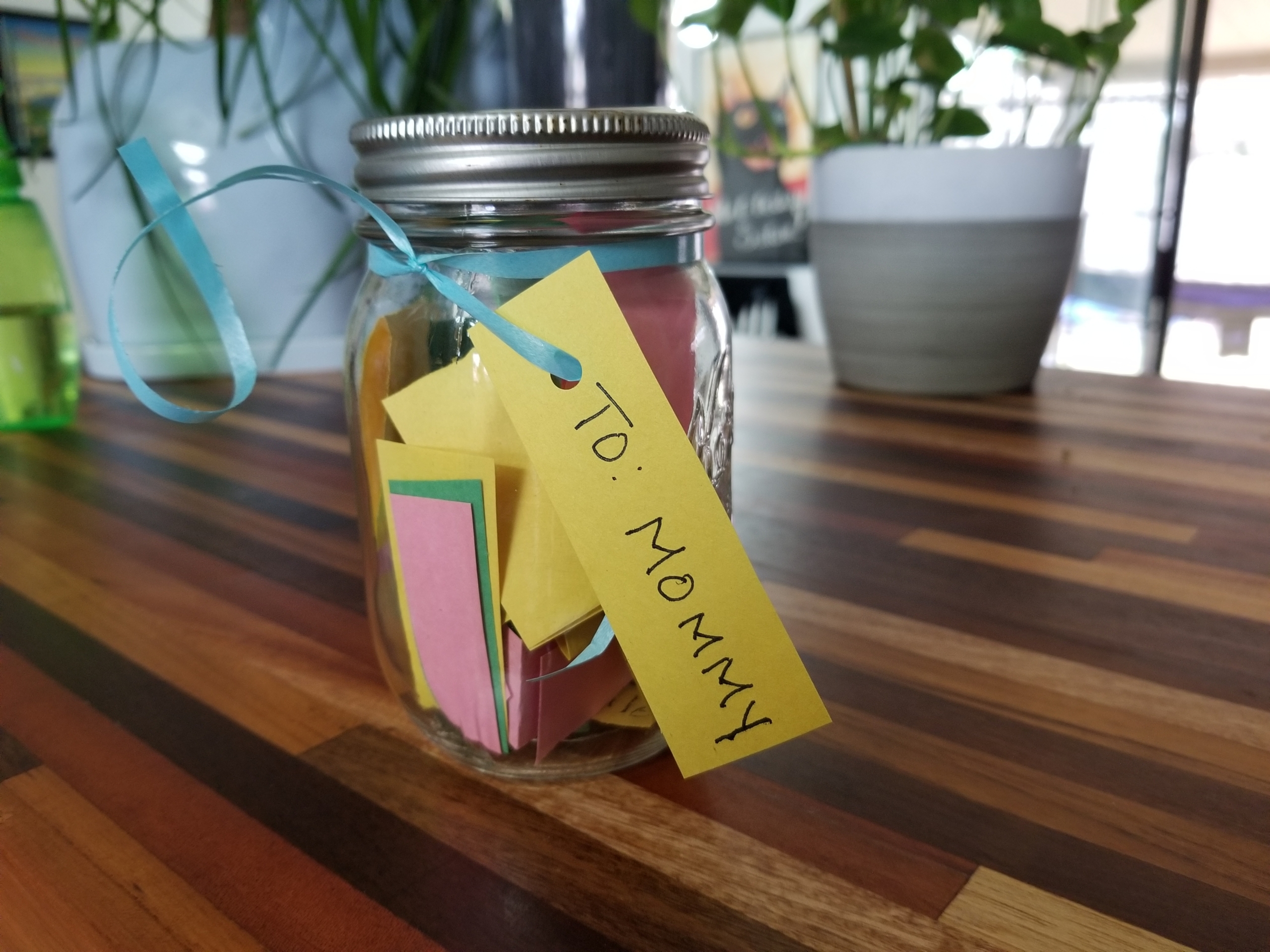

Step 7: Tie a ribbon or string around the jar and attach it to a tag with the recipient’s name on it. Now it’s ready to share!

Remember, the writing doesn’t need to be perfect! If your child needs help sounding out words or asks which way a letter faces, you can help them. However, allowing them to sound things out and make mistakes is all part of the learning process, so don’t stress out when vowels get dropped or there is a backwards R here and there. It’s about progress, not perfection.

And letting mom or other loved ones know how much they mean to your family—that’s the most important part of all.

Share with us on Instagram (mention @mayasmarty or use the hashtag #litrich) or in the comments what you put in your jar. And remember, keep your DIY Mother’s Day gift a surprise until the big day. Mum’s the word!

By Michelle Luke

Rhyming is a fun and effective way to support early literacy. It familiarizes children with the sounds that make up words, highlighting ending sounds in particular—and fostering phonological awareness, or the recognition of discrete sounds within a word. It creates a fun way for children to remember stories that they create through the pairing of common endings. And it also plants in youngsters an innate sense of syncopation, beat, and rhythm that they can later transfer to their own writing.

In this sweet Easter craft and activity, you’ll learn how to make an easy but adorable Rhyming Rabbit Easter Bunny puppet. Then you’ll help your child use their bunny to recite rhymes, from nursery rhymes and songs they know to beginner poems to come up with themselves. Using the bunny makes rhyming more fun, but it also has a deeper benefit: Reciting through a puppet can help children feel less self-conscious and free your budding poet or songster to get as lyrical or silly as they like.

See 4 Brilliant Ways Nursery Rhymes Prepare Kids to Read and Write to learn more about the power of rhyming.

Materials:

- Paper lunch bag (or any paper bag)

- Plain paper

- Scissors

- Glue, glue stick, or tape

- Colored pencils, crayons, or markers

- Printer (optional)

Cost: Nothing, if you have these simple materials on hand.

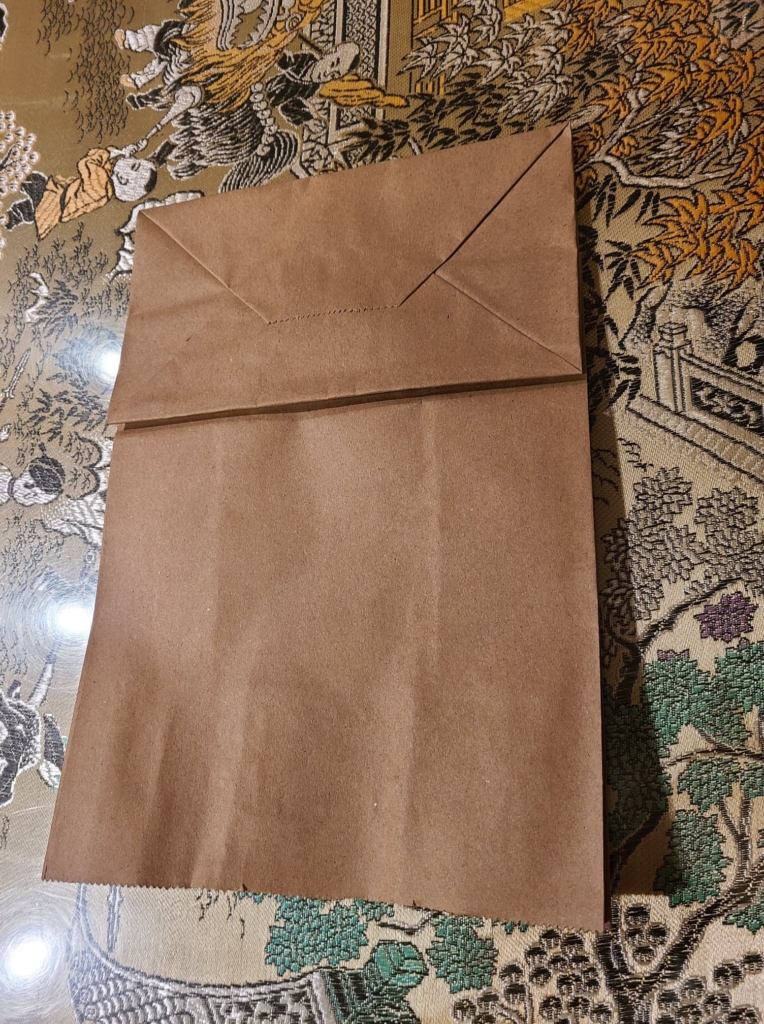

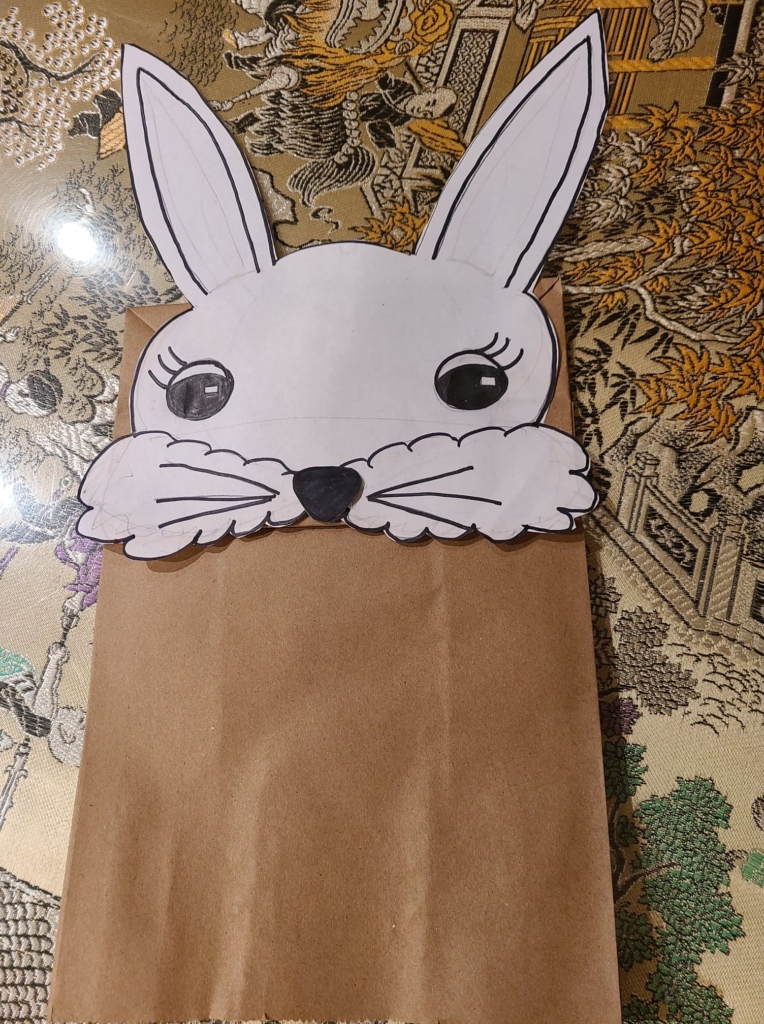

Step 1: Draw a bunny head for your puppet (or print our free printable bunny puppet template, below), then cut it out and paste it over the base of your upside-down bag as shown in the picture below. Important: The bunny’s head should approximately cover the base of your bag. If you use the bunny template, you may need to scale the image to print at the right size for your bag. Then invite your child to color or decorate the bunny.

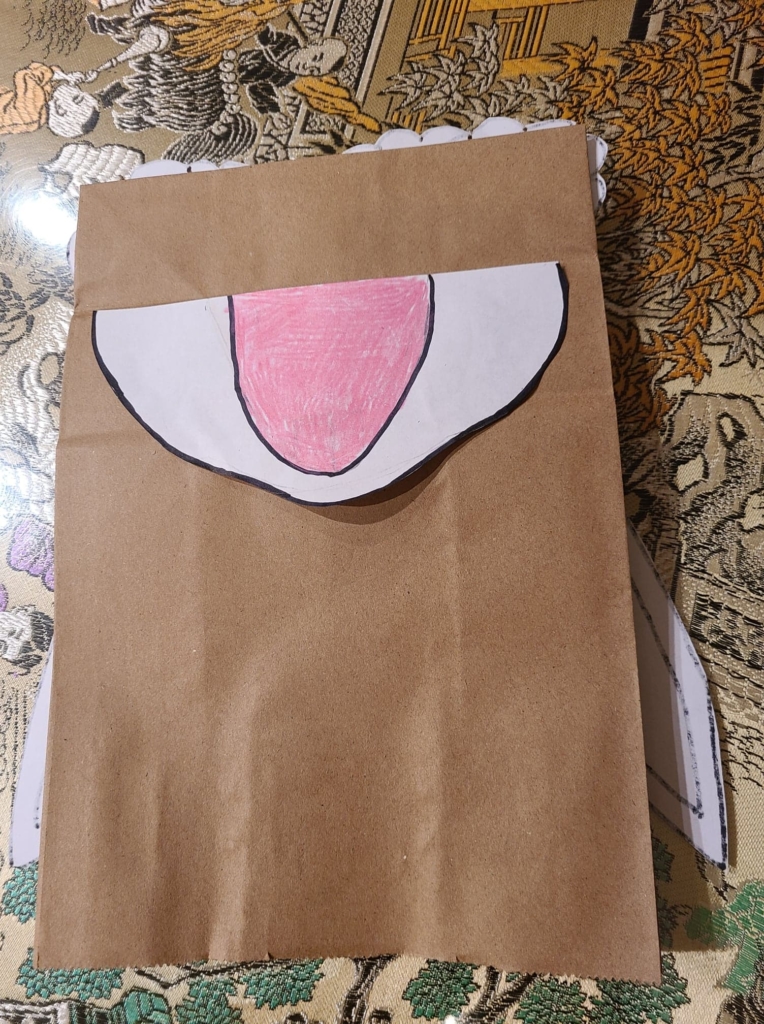

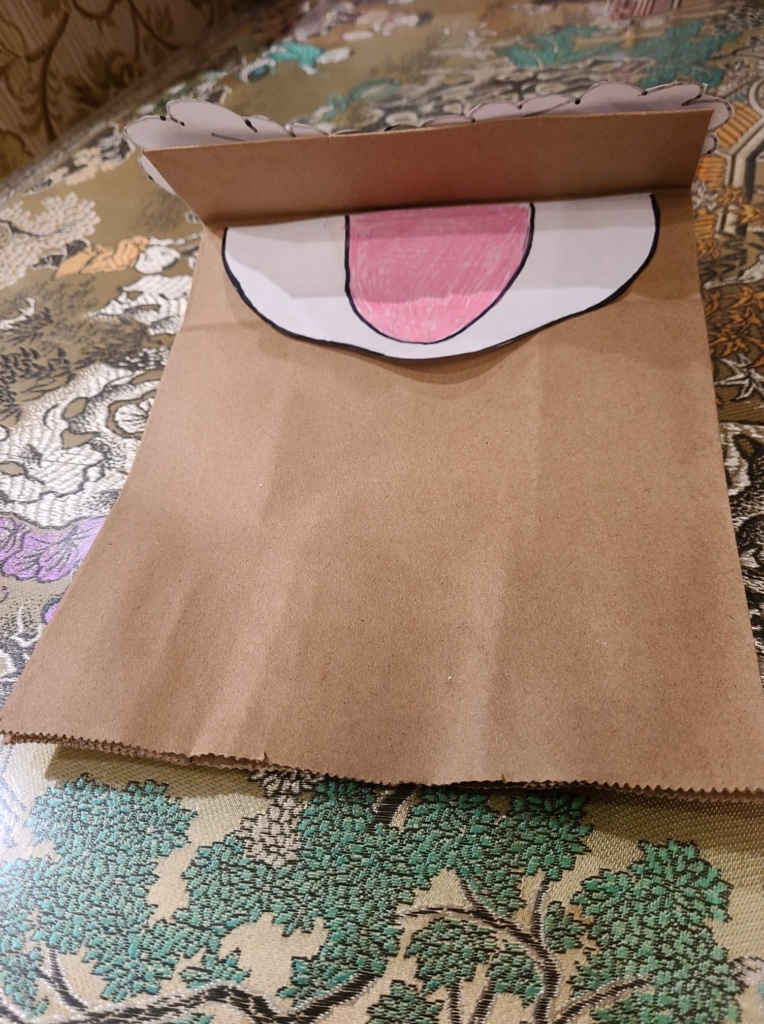

Step 2: Next, draw a mouth or cut out the mouth from your free bunny template. Attach the bunny’s mouth just below the bag’s top flap that the head is attached to, right at the crease that creates the base of the bag, as shown below.

Step 3: Finally, draw bunny feet and a cottontail, or cut them out from the template. Attach the feet at the base of the bag. Flip over and attach the tail to the back of the bag.

And your Rhyming Rabbit puppet is complete! Now your child can use it to read or sing poetry that they develop with you. Start them off by modeling how to use their puppet to recite a favorite nursery rhyme, Easter song, or spring-themed poem—or make up your own rhyme on the spot. Then help your little one develop a poem of their own.

Here’s how: Give some examples of rhyming words, and then have them join you in shouting out a word that rhymes with the last word you said. Jot them down—or help older kids write the words themselves—and then demonstrate how to recite them in rhythm to feel like a poem. This may be enough for the littlest children; for older kids, show them how to add a few words to make short lines that each end in one of the rhyming words. Have fun!

We’d love to see what you do! Share pictures of your puppet on Instagram and tag @mayasmarty.

Enjoyed this tutorial? Share it!

One of my strongest memories growing up as a child was playing board games with my family. My dad’s favorite game was Sorry! Each time he bumped my piece off the board he shouted, “Sorry! I’m not sorry!” Was my dad creating trending phrases 20 years ahead of time or secretly a songwriter for Demi Lovato? Uncertain. But one thing’s sure—30 years later, I carry the warm memory of those evenings with me.

Family game nights can be a really wonderful way to spend quality time together as a family. Board games also teach children fine motor skills, taking turns, patience, and problem solving, and they can even help improve academic skills. But, most importantly, they’re fun! I created this tutorial to help you and your children make a DIY board game that reinforces alphabetic knowledge and gives you a unique opportunity to bond.

This simple alphabet game is tailored for children from about 3 to 5 years old, so it’s easy to make, quick to play, and supports practicing basic letter sounds. Together, you’ll make and customize your ABCs board game, and then you can play it over and over, building literacy and memories along the way.

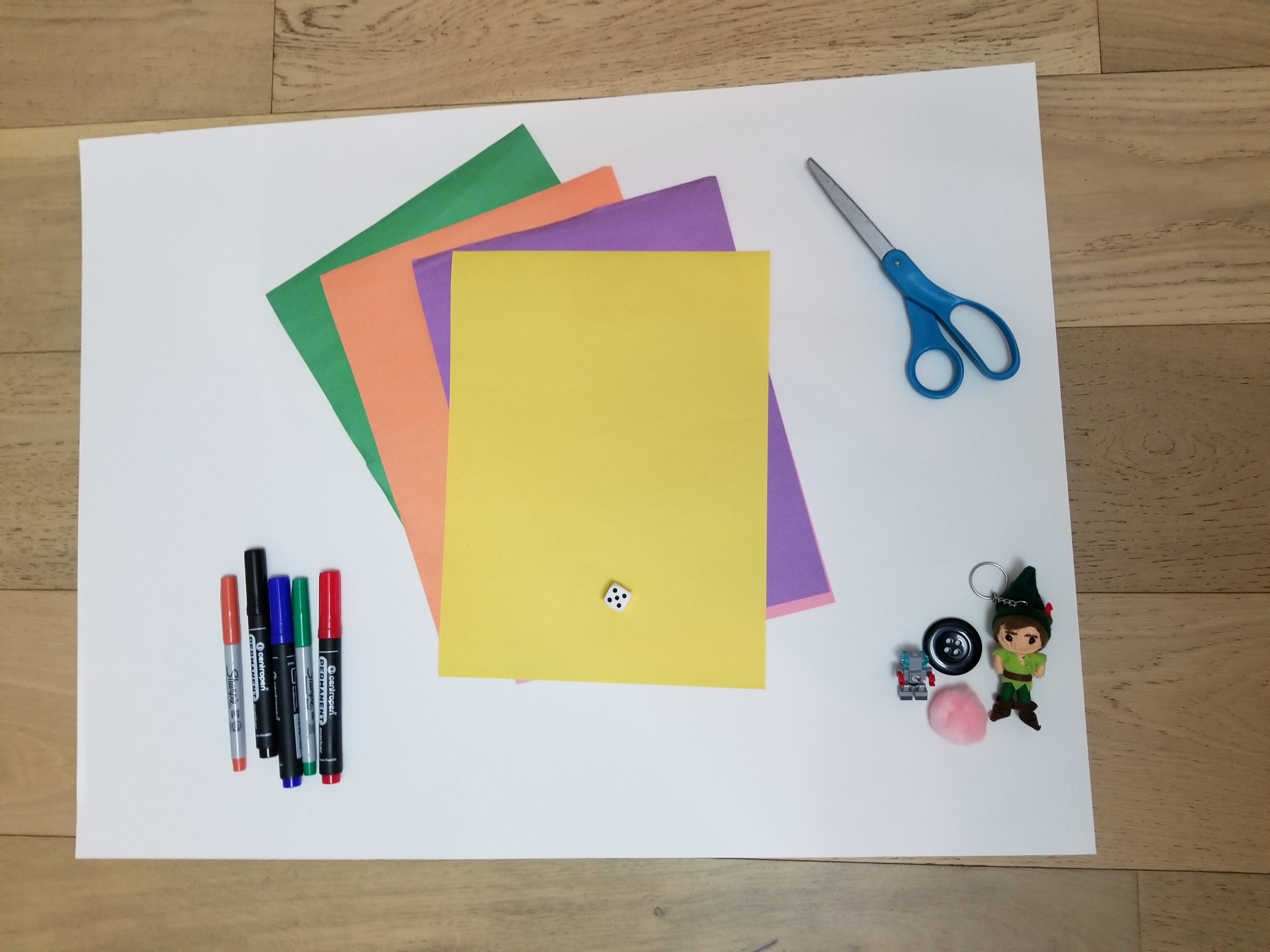

Materials:

- Poster board

- Scissors

- Markers

- 1 Die

- Small items to use as playing pieces

- Glue (optional)

- Construction paper (optional)

Cost: Around $3 for the poster board.

Remember: Let your child help you with each of these steps. Their input is very valuable and will help make sure they’re engaged!

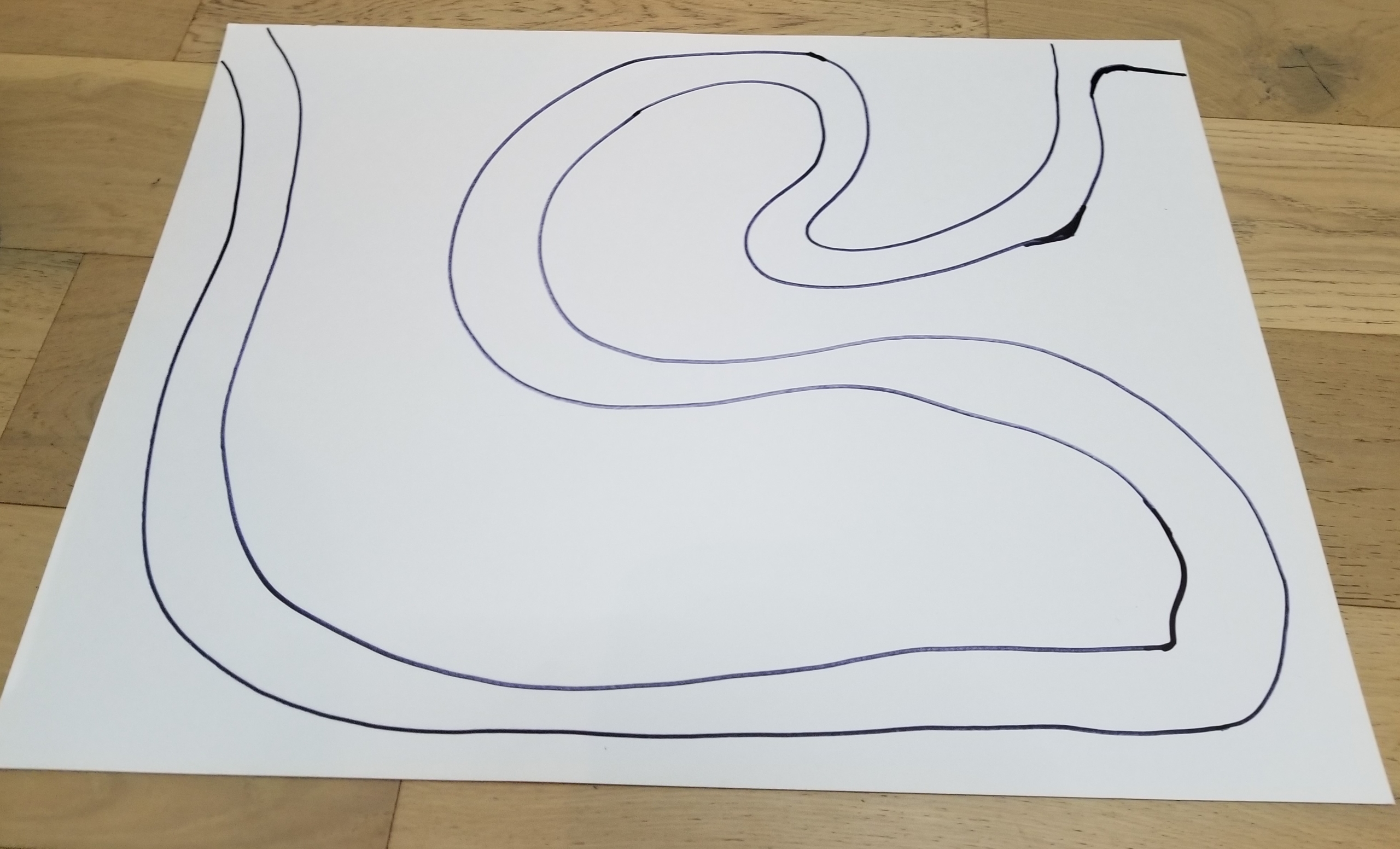

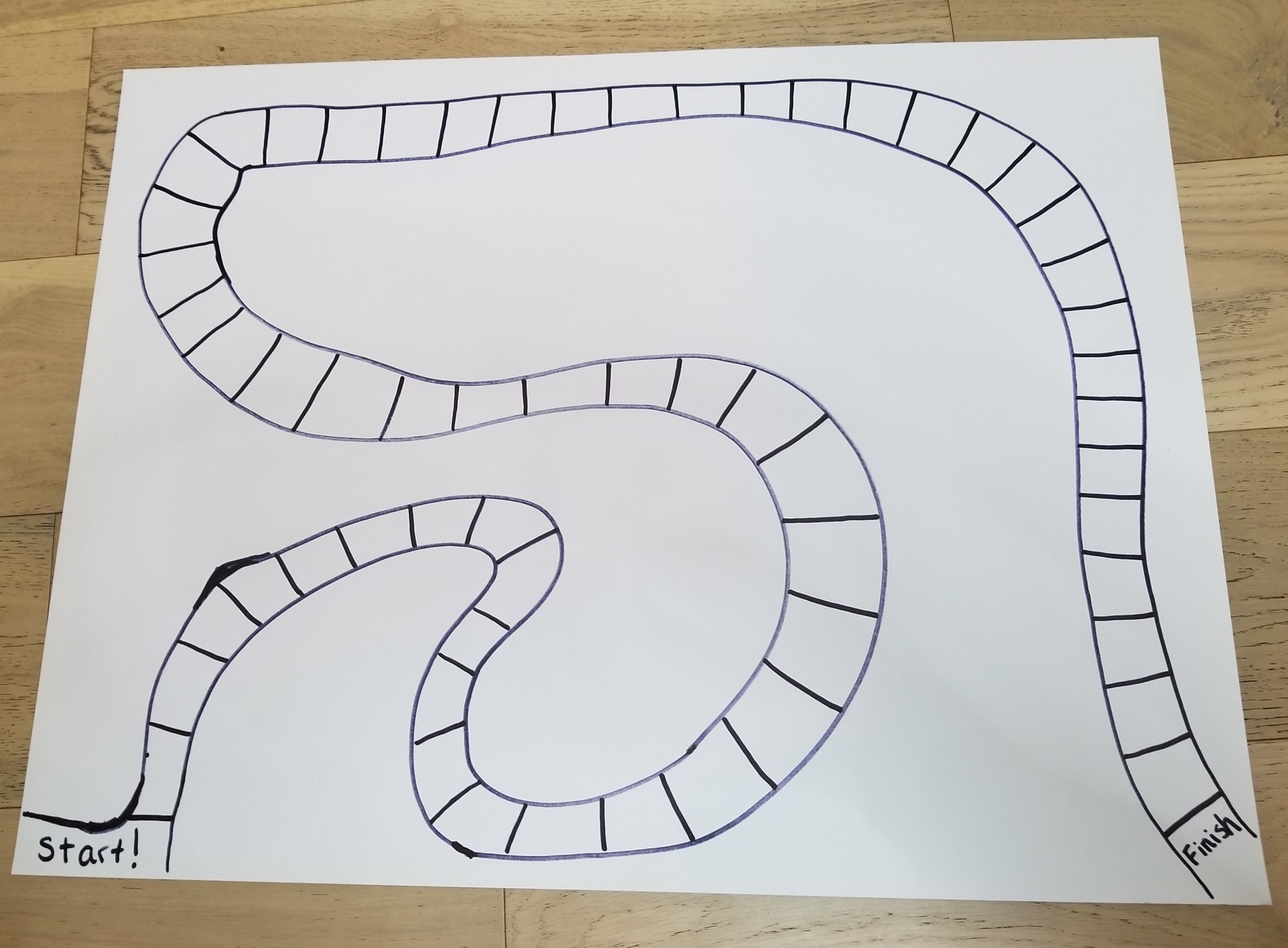

Step 1: Draw a winding path from one corner of the poster board to the other. The way is entirely up to you. Make sure it is wide enough for you to write a couple of words inside.

Step 2: Draw lines across the path, segmenting it into at least 53 spaces. Write “start” in the first space and “end” or “finish” in the last one.

Step 3: Color the spaces a variety of different colors. Or you can glue on pieces of construction paper. Make it as colorful and inviting as you like!

Step 4: In the second spot, write the letter A. Continue writing the rest of the alphabet, leaving at least one blank space between the letters.

Step 5: Now it’s time to add some fun! Write instructions on some of the blank spaces. Here are some suggestions, below, but you can also come up with your own. Personalize this game for (and with) your child.

Suggestions: “Go back 1 space,” “Sing the ABCs,” “Spell your name,” “Spell a pet’s/relative’s/friend’s name,” “Go ahead 1 space,” and “Make a letter with your body.”

Step 6: Decorate the board more! Let your child lead the way on how this should look. When I do this activity with students, our boards always end up with glitter and sequins on them!

Step 7: Play the game! See my rules below, but you should feel free to edit or create rules that work best for your game and your family. That’s the best part of creating your own board game!

Rules:

- Players go in alphabetical order.

- Players take turns rolling the die and moving that number of spaces.

- If a player lands on a letter, they say the name of the letter and something that starts with that letter. If they’re unable to do so, they go back to their previous space.

- If a player lands on a space with an action, the player must complete that action or go back to their previous space.

- If a player lands on a blank space, they can chill out that round.

- The first player to reach the finish line wins!

This game can be played quickly, perfect for the attention spans of little players (and convenient for busy parents, too!). But while it may be over quickly, the memories your family will create as you play your own customized board game will last long after the final die is rolled.

How was your family game night? Let us know!

By Michelle Luke

Easter. It’s a time of eggs and sweets, beautiful bonnets and celebrations with loved ones, and … So. Many. Plastic Easter eggs! If you’d rather keep them out of the landfill but have way too many for future egg hunts, turn some of them into literacy-supporting maracas that kids can shake along to nursery rhymes and favorite songs.

In this super-easy, two-step craft, you’ll upcycle old plastic eggs into colorful musical instruments to welcome in the spring with a vibrant lyrical celebration. Check out the instructions below, and then read on for tips on how to use your child’s new shaker for maximum brain-building benefit.

Incorporating stories and words with physical activity enhances a child’s story time by tapping into their motor skills and building greater engagement. Speaking in exaggerated, sing-song tones, responding to a child’s verbalizations, and taking turns in conversation are key behaviors that help babies acquire language and older children develop literacy. With these homemade Easter-egg shakers, you’ll incorporate both!

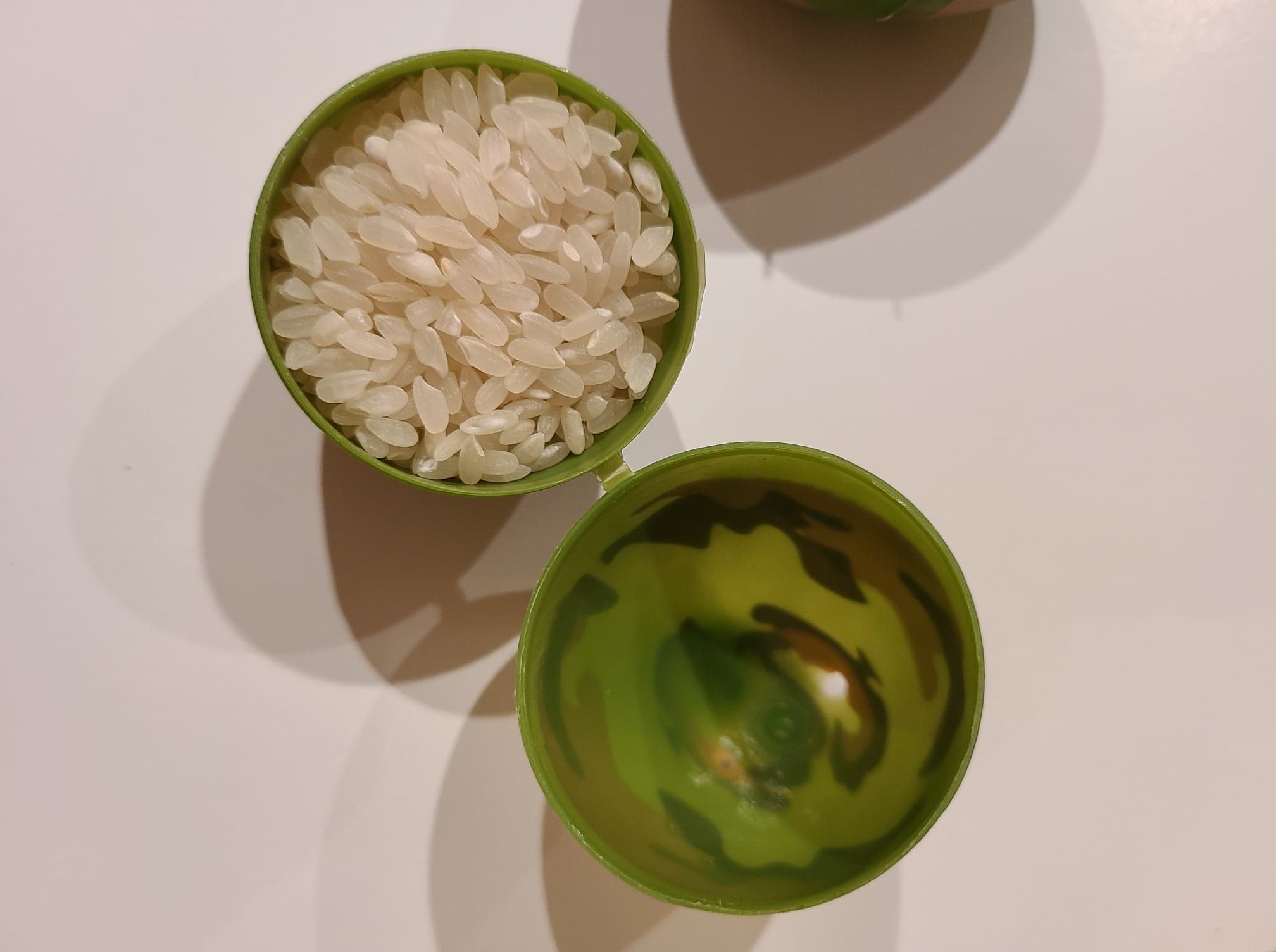

Materials:

- Plastic Easter eggs (as many as you want)

- Dry goods (rice, beans, pebbles, etc.)

- Clear tape

- Mod Podge (optional)

- Colored tissue paper (optional)

Cost: Free! (If you’re one of the rare few who doesn’t have any old plastic Easter eggs on hand, ask around! A neighbor or friend is sure to have one or a million lying around.)

Step 1: Fill your plastic egg(s) with any dry goods of your choice. Rice, beans, or pebbles all work well.

Step 2: Snap the egg shut and tape it closed with a single piece of clear tape. Make sure it’s well sealed.

Bonus step (optional!): The beauty of this craft is that it’s fun, free, insanely easy, and educational! But if you’re ready for a tad more crafting and have some Mod Podge and colored tissue paper on hand, you can also decorate your egg with a tissue-paper collage. Just tear strips of tissue paper and use the Mod Podge to stick it onto your egg after taping it shut.

Congratulations! Your egg is now an instrument that your child can shake along to a favorite nursery rhyme, poem, or song. Invite your child to recite or sing along with you, or let them take the lead. You can participate by clapping along.

Having your child use a shaker to feel the regular cadence of a rhyme’s rise and fall provides a rhythmic template for the developing brain. The emphasis of syllabic meter helps them feel the syncopation of the poem or song, as they engage with it both physically and mentally. See 4 Brilliant Ways Nursery Rhymes Prepare Kids to Read and Write to learn more.

Here are tips for using your shaker to develop important early literacy skills:

- Use your shaker to mark the syllables of your child’s favorite nursery rhyme, having them clap or shake along as you read, emphasizing syllabic meter.

- Use it to keep the beat to your child’s favorite songs, developing in them a sense of syncopation, rhythm, and beat.

- Once your child feels the rhythm of syllables and how they work together in a rhyme, work with them to develop some rhymes of their own that they can recite or sing to the accompaniment of their egg-shaker.

- Enhance the fun (and learning!) by inviting your child to perform his or her own rhyming masterpiece for family members. Hand shakers out to the “audience” to keep the beat as your child recites or sings.

- Your child can even come up with a call-and-response story, where the audience is engaged to use their shakers to emphasize a suspenseful part of the story.

Once you make the shaker, it’s yours to use in so many wonderful ways.

Liked this tutorial? Share it!

I love a good alphabet book to help kids get practice identifying, naming, tracing, and saying sounds for letters. But they are surprisingly hard to find.

Many alphabet books are designed with older readers in mind, putting more emphasis on specialized vocabulary and background knowledge than basic letter forms and the most common sounds they represent.

Some ABC books feature show-stopping illustrations that distract prereaders from paying attention to the letters at all. Others have fonts that are so faint or frilly that it’s hard to see the specific features that set one letter apart from another—the letters’ lines, curves, and humps.

Still others give too much attention to silent letters, unusual pronunciations, and other content that prereaders aren’t ready for. These may be great tools to work on spelling and reading skills with budding readers, but they’re not what you need to teach your child the alphabet.

The best alphabet books for teaching preschoolers their ABCs (and any kids who are still learning the fundamentals of reading) feature clear, bold uppercase letter forms, minimal text, streamlined illustrations, and words that begin with the most common sounds for the target letters.

There’s no perfect alphabet book—for example, very few feature the most frequently used letter sounds for every letter, as is ideal for beginning learners. But below is our list of some favorite ABC books to get you started. What’s more, each of these titles, besides giving the letters their due, also has a compelling hook that will make your little one want to read them again and again.

ABC Books that Highlight A Letter or Two

ABC Books for Teaching the Full Alphabet

An ABC Book for Teaching Lowercase Letters

If you found this post helpful, please share it!

Easter is coming, and that means egg hunts and baskets full of goodies. Chocolate and jelly beans are fabulous, of course, but if you’re like us you may be seeking additional ways to celebrate that involve a little less sugar. (And dying eggs can only get you so far.)

Don’t worry! We’ve got you covered, with various enriching activities and DIY gifts that offer plenty of Easter fun and build literacy skills at the same time.

We love DIY storytelling dice to get the ball rolling on inventing stories together with your child. This helps kids enrich their oral language, deepen their comprehension, expand their vocabularies, and develop key skills underpinning reading fluency. What’s more, it’s easy and cheap to recycle a couple of old building blocks into your own Easter-themed storytelling dice.

Make them with your child as an activity during the build-up to Easter, or craft them on your own as a cute Easter-basket stuffer. After all, the more space taken up with little novelties, the less room for sweets. And what better way to fill out your little one’s basket than free, educational, and eco-friendly surprises?

Follow the tutorial below, or try our other fun Easter activities.

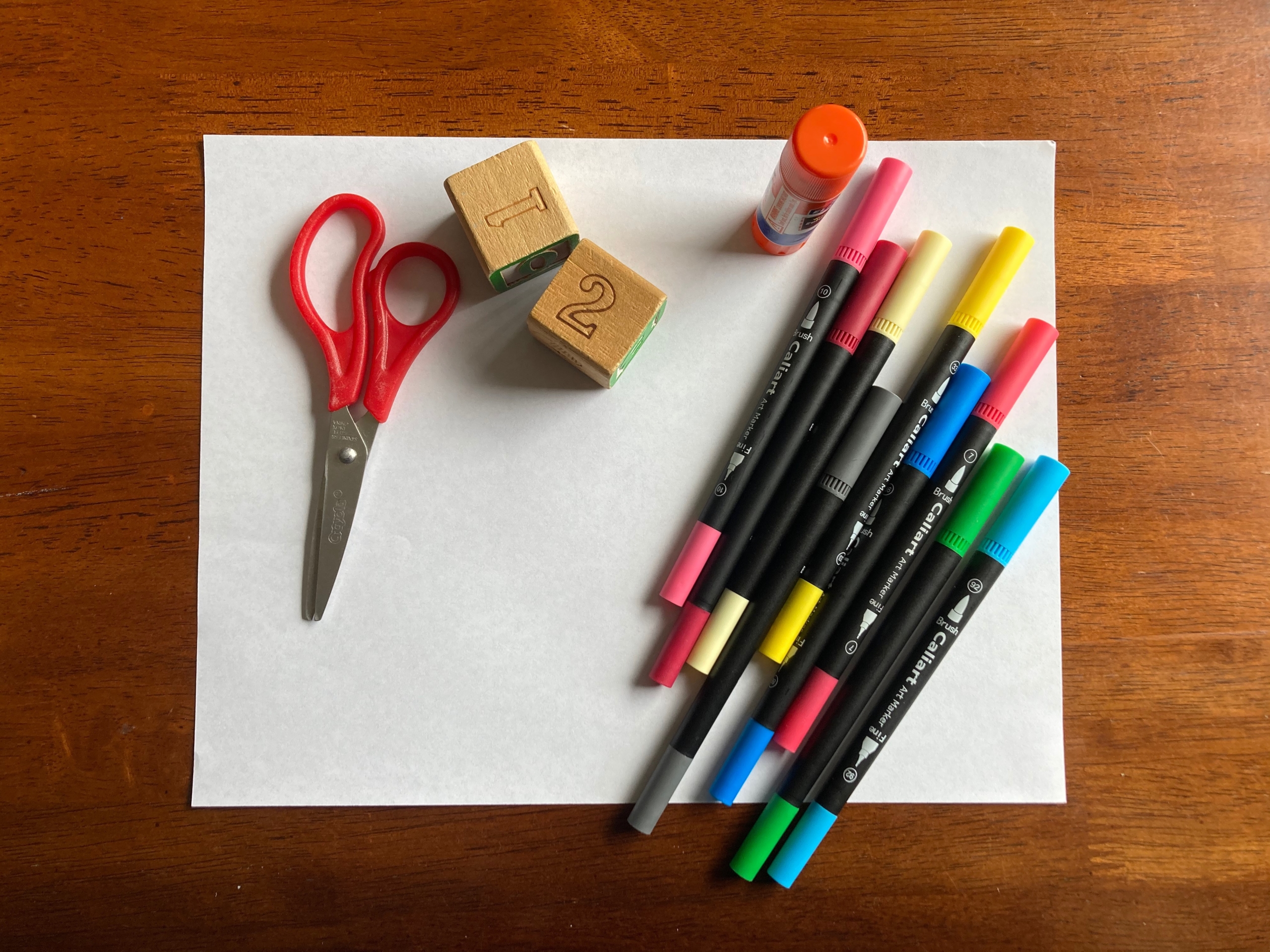

Materials:

- Square building blocks (2)

- Glue or tape

- Paper

- Markers

- Scissors

- Mod Podge (optional)

Cost: Free!

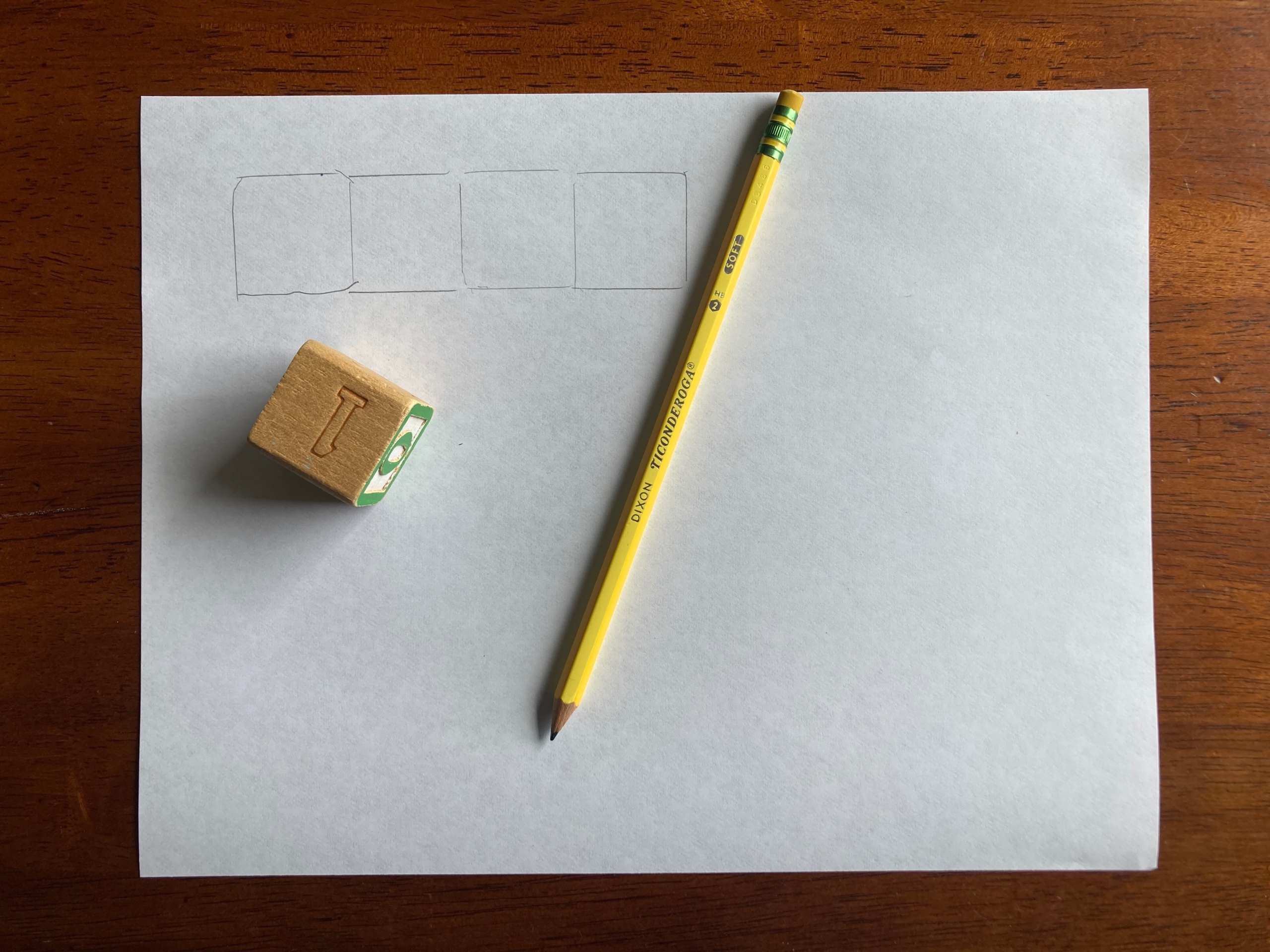

Step 1: Lay your block on a piece of paper and trace it. Repeat 12 times, to make 12 squares. Cut each square out, a little inside the line.

Step 2: Draw simple pictures of Easter and spring-related pictures on six of the paper squares. Then write the name of each item underneath it in clear printing. Then draw another set of the same pictures and labels on the remaining squares, so that you have two of each picture.

Ideas: Bunny, egg, basket, hat, sun, chick, flower, tree, etc.

Step 3: Glue or tape the squares on all six sides of your block. Opt for tape if you want to peel off the labels later and return the block to toy duty, or choose glue if you want a more lasting Easter cube. Repeat with additional blocks if you want multiple storytelling dice.

Tip: If you really want to make it last, paint Mod Podge over the papers to give them a protective finish. Do this if you’re making these Easter storytelling dice as an Easter basket gift!

Now your storytelling dice are ready! Time to play. Here’s how: Take turns with your child gently rolling the dice. On your turn, make up a story featuring the two pictures that show up when you roll. (If the same picture comes up on both dice, roll again.)

Go first, to model for your child how to create a story from the prompts. Get creative and use lots of descriptive words to really bring your story to life!

Here’s an example to get your storytelling juices flowing:

Once upon a time, on a sunny Easter morning, a bunny was hopping along in a meadow. Suddenly, she spotted the most beautiful flower she’d ever seen in all her life.

As she stopped and looked around, she realized she’d entered a patch of radiant blossoms in every color of the rainbow. Luckily, she had her Easter basket with her, so she began gathering flowers to take back to her mother, when suddenly …

On your child’s turn, encourage them by listening attentively to their story, showing surprise and excitement as appropriate, laughing out loud if something funny happens, and generally demonstrating that you’re engaged in their story.

As you play, you can gently point out the labels below the pictures. This will help even the youngest kids to develop print awareness and learn that words represent objects. And older kids can begin connecting up the sounds and letter combinations with the items on the dice.

If you’re ready for more complicated stories—or just need more inspiration—roll the dice more than once per turn and take note of all the pictures that show up.