I’m a teacher, and as November approaches, parents often ask me to recommend books by Native American authors or with Native American characters. I always have a list handy. But it got me thinking: Why now; why November?

Well, we know the answer, of course. Thanksgiving. It’s generally the only time of year schools and media celebrate the contributions of Indigenous Americans to the current version of this nation. What’s more, many kids’ Thanksgiving books tell a similar (and often falsified) story of the first Thanksgiving.

As parents, you have the power to change this just by the books you put on your children’s shelf—all year long. Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop, a leading multicultural children’s literature expert, says, “Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror.”

By making sure your child has access to quality books by and about Native Americans all year long, you can create those mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. This post will show you how.

How Should We Choose Picture Books About Indigenous Americans?

This is a great question and the answer is important. There are two good ways to choose:

- Look for kids’ books by Indigenous American authors. Often the author’s bio on the book jacket will tell you. If not, you can typically find the answer in a two-minute Google search.

- Also, read the book before you buy or borrow it. Does the book frame Native Americans as “others” or compare them to white people to make it “relatable?” For example, phrases like “Today, Native Americans dress the same way we do.” If so, pass on those. Does the story center Indigenous American characters and create authentic, well-rounded stories? Then get it!

Happily, in the past few years, more Indigenous American authors have been getting published and winning awards. We Are The Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom even won the Caldecott Medal in 2021! Because of this, it has become even easier to include such stories in your child’s life.

Awesome Kids’ Books by Indigenous Americans

For some great books to get you started, here are a few of my favorites:

Mission to Space by John Herrington

Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story by Danielle Greendeer, Anthony Perry, and Alexis Bunten

We Are Water Protectors by Carole Lindstrom

I Sang You Down From the Stars by Tasha Spillett-Sumner

My Heart Fills with Happiness by Monique Gray Smith

We Are Still Here by Traci Sorell

The Walrus and the Caribou by Maika Harper

Where to Find More Ideas & New Books by Indigenous American Authors

You can also check out the American Indian Youth Literature Awards for books for children of all ages. To dig in further and find more awesome recommendations in real time, follow these accounts on Instagram to find reviews, releases, and recommendations:

- @indigenouseducators

- @indigenousbookshelf

- @thunderbirdwomanreads

- @paperbacks_n_frybread

- @massybooks (a female Indigenous owned bookstore)

- @mollyofdenali (a PBS Kids show about an Alaskan Native girl)

Why and How to Build an Inclusive Library for Your Kids

As you build out a more inclusive bookshelf, keep in mind that quite often children’s books about Thanksgiving feature racially insensitive stereotypes about Native American characters and give the false impression that Indigenous Americans:

- lived a long time ago and no longer exist

- had/have a single shared culture, religion, and language

- only exist(ed) to serve as guides or “assistants” to white people

Indigenous Americans live and exist in the United States 365 days a year. There are 574 federally recognized Native American tribes within the United States. As such, books by and about these Americans deserve to be celebrated on your bookshelves and in story times all year round.

This will help families of all backgrounds counteract the white Euro-centric viewpoint kids can learn when they only see white children in picture books. In turn, it will prepare them to act with empathy for others. And for Native American children, seeing themselves represented in a positive light will empower them and give them self-confidence to speak up for themselves and positively advocate for their communities.

Change can begin on your bookshelf. Investing in quality picture books about Native Americans will affect your child as well as the lives of others. It’s a ripple in a pond. Keep sharing books by Indigenous American authors all year round and watch those ripples grow.

Picture this. It’s Christmas eve, and your family has gathered to give each other books, then cozy up for an evening of reading and hot chocolate. (Maybe throw in a roaring fire and marshmallows for good measure). Sound almost too good to be true? Meet the Icelandic Yule tradition of Jolabokaflod, which means “Christmas book flood”—a festive celebration of reading and simple pleasures.

The tradition has been going strong for more than 75 years in Iceland. Over the last few years, it’s been capturing imaginations beyond the Nordic island, resonating with book lovers and those seeking a more conscious holiday experience versus unsustainable consumption. After all, what could beat giving loved ones, and especially your children, the gift of reading—and all the treasured memories that go along with it?

So, if you’ve been searching for fun and rewarding Christmas traditions for kids—and grown-ups—this holiday season, maybe it’s time to start your own Jolabokaflod. But what exactly does it consist of? How should you go about it?

This article will answer those questions. As with so many of the best ideas, its appeal lies in its simplicity.

The Story of Jolabokaflod, the “Christmas Book Flood”

Iceland is a nation of readers, boasting one of the highest literacy rates in the world (99 percent) and reporting more published books per capita in recent years than almost any other country. Its literary heritage stretches back through the ages to the famous Norse myths and sagas recorded on the island in medieval times, and it remains at the core of Icelandic cultural identity today. Stories have been a flame to see its people through the long, dark nights of their far-north winter. No wonder, then, that it was there that such a strong book-giving Christmas tradition took root.

In 1944, paper was one of the few commodities that wasn’t heavily rationed due to World War II, yet Icelanders had money to spend on Christmas gifts. The solution? Going all-in on books as gifts. The publishing trade sent a “Book Bulletin” catalogue to every household to make placing Christmas book orders extra easy, and so the Jolabokaflod tradition was born.

Fast-forward to today and the Book Bulletin still goes out every year during the Reykjavík Book Fair in November—alongside a flurry of literary events—marking the beginning of the “Christmas book flood” season. It’s a time when books become the talk of the nation.

Iceland’s literary scene is thriving, its authors published in translation throughout the world (Nordic noir is an especially popular genre). Writers are respected. Supposedly one in 10 Icelanders eventually write a book. And there is even an Icelandic saying: “Everyone has a book in their stomach,” meaning “everyone gives birth to a book.” In 2011, Reykjavík was the first city with a native language other than English to become an UNESCO City of Literature.

The ripple effect of Jolabokaflod has had a lasting and profound impact on Iceland’s people, arts, and economy.

The Joy of Jolabokaflod and Book Gifts for Christmas

These days, the “Christmas Book Flood” may come with more marketing hype and author competition than when it first started out, but its spirit remains true to Icelanders’ deep love of books and stories, perhaps best summed up by people who grew up with it.

As author Hallgrímur Helgason puts it, “Thanks to Jolabokaflod, books still matter in Iceland, they get read and talked about. Excitement fills the air. Every reading is crowded, every print-run is sold … At the average Christmas party people push politics and the Kardashians aside and discuss literature.”

Gerður Kristný—Icelandic poet, novelist and children’s writer—recalls, “I have always been given books for Christmas. I remember vividly being an 11-year-old getting nine books that year! Looking at the pile I felt very grown up.”

“Nothing has prepared me better for life than the books I read as a child,” continues Kristný. “They taught me what kind of a world I wanted to live in as an adult and how I could be a part of making it fair and just. They also showed me into worlds I would never otherwise have entered.”

In today’s economically unpredictable times, books remain one of the more affordable luxuries—small investments that deliver rich rewards. And, as well as providing opportunities for relaxing holiday downtime and enjoying the benefits of reading together, bringing books into the heart of your Christmas family tradition gives your children a powerful, and long-lasting message: that books are special and reading matters.

Are you ready to include Jolabokaflod in your Christmas traditions?

How to Hold Your Own “Christmas Book Flood” this Holiday

One of the lovely things about Jolabokaflod is you can go as big or small as you feel like.

In the run-up, get your kids excited by talking about your “Christmas Book Flood” and encouraging them to suggest ideas for making the evening special. You could ask them to share their “wishes” for books or book themes, browse bookstores together, or attend some children’s author events in your area. In turn, ask them to choose a book for you or another family member to read. Want some instant inspiration for choosing great children’s reads? Check out our book lists!

Remember this is your Jolabokaflod, so if you don’t want to buy your books new, you don’t have to. You could find your books in a thrift store or book market, or even pass on a treasured book of your own. Nor do you need to stick to the literal meaning of the expression and “flood” your family with books. A Secret Santa-style exchange, with each person giving and receiving just one book each, can work just as well.

On the day, take time to savor the celebration. Get creative with wrapping. Prepare snacks and hot chocolate together. Make your reading chairs and book nooks extra cozy with throws and cushions, and add the twinkle of fairy lights.

Find ways, too, to personalize the book-giving—people might want to inscribe and date the books they’re giving, or share why they chose a particular title. Then enjoy snuggling up together and poring over those lovely new reads!

In the days that follow your “Christmas Book Flood,” keep the book love flowing! Talk about the books you each received and read. And why not try some book-related craft activities and games? These can enrich the experience, as well as provide fun, screen-free holiday time and further learning opportunities. Maybe everyone could write a short review or draw a picture about their book—these could be turned into a collage or kept in a Jolabokaflod box that comes out every year.

However you choose to celebrate it, the “Christmas Book Flood” might just end up becoming one of your family’s favorite holiday traditions for many winter seasons to come. Happy book giving!

With the holidays approaching and shopping lists and letters to Santa getting longer every day, it’s easy to get stressed looking for the perfect gift. So we’re making holiday shopping just a little bit easier. We’ve compiled a list of terrific educational gifts for preschoolers that will become household favorites the whole year through. These fabulous gifts spark early learning and a love of reading in your child. And best of all? None of them sing or have flashing lights.

Educational Gifts for Kids Who Can’t Read Yet

Orchard Toys Big Alphabet Floor Puzzle

This giant floor puzzle is so fun. It’s bright and colorful and has illustrations kids are drawn to. My favorite part is that the puzzle features lowercase letters rather than uppercase letters. So your child will be learning an important new literacy skill. With its large pieces and simple shapes, this gift is great for ages 2-4. I bought this puzzle for my own nephew and he began to understand the alphabetic order while assembling this puzzle. He also began to ask questions about why letters matched the pictures, introducing him to letter sound correspondence. A big thumbs up from me (and my nephew).

Storytelling cards like the Create a Story set from eeBoo are fantastic fun and learning for kids long before they begin reading, though they remain fun for years after, too. These are sets of cards with pictures on them meant to inspire storytelling. There are different themes, so you’ll be able to find a set that appeals to your child. The child can lay out cards in any order and create their own story right in front of their eyes. When they’re finished, they’ll love explaining the plot to you! Alternatively, you can spare your wallet (and the planet) by making your own DIY story cards or story cubes by upcycling an old card deck or a few building blocks.

Montessori Phonetic Reading Blocks Wooden Words Spelling Game

These blocks are fantastic for children who are ready to start learning to read simple words. They’re strong, interactive, and a great practice tool! Children spin the blocks around and learn to spell and read basic words. The blocks come with cards, so children can replicate words and match them to an image. However, children can also play with them independently and learn how to sound out words that they create themselves.

If you are a fan of the Montessori learning method, you’ll really like these Montessori language objects. These collections of small materials align with different phonetic skills. For example, some collections contain objects whose names rhyme, and others have groupings of objects whose names start with the same letter sound. The small items help children learn to associate letters with sounds while playing. They make great stocking stuffers, too!

Touch Think Learn: ABC by Xavier Deneux

This beautiful board book combines dynamic graphic art with uppercase letters. It’s tactile and fun for all your little learners. This book is great for helping young kids identify letters and introducing them to the sounds that letters make. Your child will fall in love with their ABCs with Touch Think Learn: ABC. (Plus, see our list of awesome alphabet books for more book ideas.)

Educational Gifts for Kids Who Are Starting to Read

Create Your Own 3 Bitty Books Kit

For the little budding author in your life, this make-your-own-book set from Creativity for Kids will be an inspiring gift. The set includes three blank hardback books (yay, durability!), markers, and stickers. Your child can dictate stories for you to transcribe, then they can illustrate them. If your child wishes, they can simply create an illustration-only picture book. As your kids are ready to tackle writing themselves, these books are a great opportunity to sit together to practice sounding out and writing words to create their own story. Their creativity will flourish, as will their love of books. Once they’ve finished their literary masterpiece, they can read their story to you. What a wonderful way to choose a bedtime story!

Mad Libs are a great gift for older preschoolers! They’re a fun stocking stuffer for your child and a playful, silly way to spend some time together. Even if your child can’t read or write yet, they’ll love supplying you with words for the Mad Libs, and you’ll be teaching them about nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. There are dozens to choose from, so you’ll be able to find one for every child you know!

uKloo Early Reader Treasure Hunt Game

This game is set up as a treasure hunt. The adult hides cards throughout the house. The child must read a clue on each card in order to find the next card. What if your child doesn’t know a word? There’s a visual printout included to help your child learn to read new terms. The game also has three difficulty levels, as well as wipe-off write-your-own cards, so it can grow as your child’s reading skills do!

Early Bird Readers from Lerner Books

Say goodbye to outdated Dick and Jane and colorless BOB books. These lively books are wonderful early readers. They’re funny, brightly colored, and organized into color-coded difficulty levels. The books are well thought-out and well paced. The stories grow longer with each level and at a certain point even begin to include fun comprehension questions. These books are dynamic, so children don’t feel like they’re being forced to do practice reading. I highly recommend these!

Designed for kids 4 to 9 years old, This goofy game teaches children to read common words as they compete to be the first kangaroo to get some pizza. What’s really nice about this game is that there are three levels with increasingly difficult words. This means the game can grow with your kids, and it also means that if you have multiple children at different reading levels, they can still play together, each with their own personal set of challenges. Another aspect I like is that the players can compete against one another OR you can play a cooperative mode, where everyone works together. The flexibility and fun is really what puts this game on my list. And, after all, shouldn’t reading be fun?

Educational Gifts For Children of Any Reading Level

Literati Kids Club Subscription

Like Stitch Fix crossed with a library, Literati is a book subscription service that’s fun and fabulous. You sign up for a group based on your child’s age and then each month you receive a box of books. It starts with board books and goes up through high school. Keep the ones you like, send the rest back, and only pay for the ones you keep. You also get a monthly art print and cute little extras like stickers or temporary tattoos. A fresh stack of books each month—what could be better? Having new reads available keeps kids engaged and eager to read, and it keeps the adults in the household from getting burned out reading the same tattered tales again and again.

Homer is a digital reading program for kids. It serves kids from two years of age just learning their letters to first graders working on fluency and comprehension. It has fun games, adorable characters, original fiction and nonfiction stories, and adaptations of well-loved favorites like Thomas the Tank Engine or Angelina Ballerina. Children learn how to read through song, animations, interactive readers, and excellent curriculum. Their program can be done on a tablet or on a computer, so it works with the technology that best suits your family. Kids are so enthralled with Homer that they feel as though they’re getting playtime as they learn.

Epic is, well … epic. It is a digital collection of tens of thousands of books, audiobooks, and educational videos. Your child (or any child you know) will love the ability to browse and choose the content they want. Adults love that it is a safe digital platform that’s educational too. You can learn more from our post How to Get Your Child to Read More at Home with Epic! Digital Library.

Give the Gift of a Book Date

This gift isn’t one you can easily wrap. Buy the child you love a gift card to a local bookstore. Then, choose a day and time to go together on a book date. Tell your child that they can use the gift card to buy books—whatever book they want and however many the card can cover, but they have to choose a book. (Otherwise you might end up with $25 worth of fairy tattoos.) You can explore every area of the bookstore, taking time to read stories together, finding old favorites from your childhood, asking the store clerk to help you find books on rocket ships or baseball or mermaids, or just marveling at how many Llama Mama books there are.

A love of reading doesn’t just happen overnight. Children must be introduced to books and reading. It can come through reading together at bedtime or snuggled up on a rainy day. It can be as simple as finding letters on a cereal box. But the more fun you make reading and the more pockets of joy you create surrounding books and words, the more your child will feel drawn to reading themselves.

Whether it’s for your own little ones, or the children of friends and family, these great educational gifts for preschoolers and toddlers will make everyone on your list happy. (No batteries required.)

Like this post? Share it!

You know Dasher and Dancer and Comet and Vixen. But do you recall the newest Christmas character of all? I mean, of course, the Elf on the Shelf. This little magical Christmas elf has found its way into millions of American homes and sparked a modern-day Christmas tradition.

The concept behind the Elf on the Shelf is simple. It’s a small toy elf that arrives at your home a few weeks before Christmas to watch the children of the house and see who’s being naughty or nice. Each night, the elf flies back to the North Pole to report to Santa, then flies right back to its adopted home. Families name their elves, love their elves, and design elaborate outfits and scenarios for their elves to show up in each morning.

It can be great fun and stir up the feeling of magic so often associated with Christmas. However, it can also create a hole. Because the elf is purportedly there to report on kids’ behavior, and that behavior leads to getting gifts, a child’s relationship with the elf can tilt away from Christmas values such as charity, togetherness, and love. But it doesn’t have to be that way. In fact, you can make your elf a tool for social-emotional learning, family bonding, and literacy! Just turn your elf into a Christmas pen pal for your kids.

How and Why to Start an Elf on the Shelf Pen Pal Tradition

Kick off the season by having your elf show up with a note addressed to your child(ren) on the first morning it appears. The elf should initiate the pen pal relationship and request a reply.

Later in this article, we’ll share some more tips on what to write. But first, let’s look at why this activity is so valuable.

1. It fosters social-emotional learning.

Children watch how the adults around them act and react. If, at Christmas, the adults are consumed with buying and wrapping presents, children think that gifts are the sole point of the holiday. Commercialism and “me” thinking will become its cornerstone for them.

Developing a pen pal Elf on the Shelf activity opens up the opportunity for your children to grow their social-emotional skills, instead. Unlike Santa letters, which are primarily centered around what they can get, these letters are focused on connection, empathy, and communication. That’s why this simple Elf on the Shelf idea is so revolutionary.

When writing these letters, steer your child to ask questions about the elf. Where are they from? What is it like being an elf? Do they go to school? And so on. Then, when you write as the elf, include questions that allow children to reflect on themselves. Beyond just questions about how their day was or their favorite color, you can ask about their feelings, hopes, or dreams. Talk to one another about traditions or values your family shares, either through your letters or directly as you sit together to write to your elf.

By making these moments with your child about others as well as themselves, you will help foster their social-emotional development.

2. It facilitates family bonding.

Writing letters with your Elf on the Shelf is a sweet way to strengthen family bonds. Letter writing allows you more festive time together that’s outside of gifting and receiving. It also allows you insight into how your child thinks and other aspects of their personality they may have trouble communicating verbally.

If there are older children who don’t believe in Santa, you might invite them to help you write the letters “from the elf” to their younger sibling. This way, they’re still included in the family activity and are able to feel that they’re creating a magical Christmas for their sibling. It’s all about making this Elf on the Shelf activity something for the whole family!

3. It develops your child’s literacy.

By writing letters to your elf, your child will be able to practice the art of correspondence, as well as building their awareness of writing skills. Whether you write their letter for them or they write it themselves, they’ll be developing their knowledge of how writing conveys speech.

For kids old enough to transcribe their own letter, they’ll be practicing important skills from handwriting to spelling, capitalization, and punctuation. They’ll also learn how to translate their thoughts to a page. When children tell stories verbally, they can get repetitive (“and then, and then, and then, and then, he, um … and then”). Writing allows them to slow down and clarify their thought process, to think about the words they choose and want to share with others.

And reading your elf’s notes will add one more opportunity for kids to develop their reading and comprehension skills, whether they read the letters on their own or you read them aloud. Your child will be looking for answers to the questions they asked their elf, and eager to see what questions their elf has for them. Especially since the elf is going to share a magical world with them that they can’t see. This attentiveness fuels your child’s comprehension.

Tips for Your Elf on the Shelf Pen Pal Activity

- Hand-write the letter clearly, or type and print it out, making sure it’s clear it’s from the elf. If your child isn’t reading yet, point out the letters and words as you read the note aloud to them. Show them what words you’re reading and point out some of the letters that key words start with (such as their name or “elf”). For beginning readers, encourage them to read the letter on their own.

- Write in words and sentences that are on your child’s comprehension or reading level. It’s okay to give challenging words, but overall, make it as accessible to them as possible.

- Whatever your child’s level, support them in writing back to the elf themselves. They can dictate their letter and then you hold their hand and guide them to write their names, or they can write some or all of the words as you tell them which letters form the words they want, or they can take the lead. Find the level that’s right for your child.

- In the letters “from the elf,” ask specific questions to prompt your child to write a response.

- When writing back to your child, make sure to respond to any and all questions they asked the elf.

- Help your child write their responses to the elf by making it a special time of day.

- Keep it fun! Encourage this as a fun Christmas activity rather than homework or a task that must be accomplished.

Christmas can become a hectic time that’s filled with endless to-do lists, parties, and presents. By carving out the time to form this new tradition with your family, you’ll be demonstrating for your child what really matters at this time of year—relationships.

Thanksgiving—it’s not just the day before Black Friday.

So, if you’d like to cultivate more than your family’s appetite this year (though we fully support that, too!), we’ve curated some of our best articles to help you build gratitude, kindness, togetherness, and love this season. Now there’s something to be thankful for!

Read Stories Together to Build Empathy and Kindness

Writer Andrea Hunt reports on the evidence that reading fiction can help foster empathy, which she shares is increasingly recognized as a “superpower” in fields from education and business to science and technology. She shares that empathy is believed to increase everything from personal satisfaction and creativity to leadership and negotiation skills.

But, she says, empathy is declining and the U.S. has an “empathy deficit,” according to researchers. “It appears that as a society we’re becoming more narrow-minded, more disconnected,” Andrea writes, but “making a habit of it—for example practicing loving-kindness meditation—can make our brains grow.”

Read Andrea’s article on how reading fictional stories can help your child develop emotional intelligence. Then check out her curated list of picture books that support empathy.

Teach Kids Gratitude with a Sweet Craft

As adults, we may recognize that gratitude contributes powerfully to our mental and emotional well-being, and that practicing appreciation makes us happier as people. That it supports us to be more resilient and improve our relationships.

And sharing this knowledge with our children can be a priceless life lesson. As contributor Penny Sebring reports, a 2019 entry in the Journal of Happiness Studies found a positive correlation between gratitude and happiness in children as young as five years old. Numerous other studies have also found that gratitude can improve children’s and teens’ empathy and overall sense of satisfaction.

That’s why Penny put together a Thanksgiving craft tutorial to make super-cute “words-of-gratitude” paper-chain animals. The craft emphasizes gratitude as you create adorable Thanksgiving decorations (and sneaks in some reading, writing, and spelling practice too)!

Cultivate Kindness by Supporting a Great Cause

You can help your family build emotional intelligence and cultivate thankfulness by engaging in an act of kindness together. Helping out a good cause will make your child proud and teach them they can take positive actions to make the world better, a very empowering realization.

There are many options to make a difference, from volunteering at a food bank to helping a neighbor to donating to a cause. And one cause close to our hearts is fighting illiteracy in our own neighborhoods and around the world.

Contributor Chrysta Naron curated a list of organizations around the world that support literacy and could use donations, volunteers, and books. Check it out for opportunities to make an impact this season.

Slow Down and Cook Together

This one may seem obvious on Thanksgiving, but the fact is that with small children, it can feel easier to cook without them. It’s well worth the trouble to do a little cooking together, though. The connection you build and interaction you share will set them up for success and fulfillment in so many ways, including developing language skills key to literacy!

Our Read With Me Recipes for Kids provide quick, easy recipes to make with small kids—in a printable format that’s specially designed to help them develop print awareness and reading skills. Try it out with our roasted pumpkin seed recipe, maybe with the seeds from a pie pumpkin!

Just keep in mind that while hours spent pottering in the kitchen together may sound idyllic, for cooking with the youngest kids to be successful, you should probably think more in terms of minutes than hours. And adding to family stress is definitely not the point. So our Read With Me Recipes are intentionally quick and simple to make. Bon apetit!

Put in Quality Time Doing a Fun Learning Activity

If your little one thinks you’re always on your phone (well, after all, someone has to work/shop/check Instagram!), cooking dinner, or otherwise not paying enough attention to them, the holiday may be a great opportunity to slow down for some quality time. And sitting down to make some old-fashioned crafts together is a fun way to do just that.

In addition to the sweet paper-chain gratitude animals above, we have some other project tutorials that are perfect for the season. Check out our turkey letter-matching game or a fall-themed clip-card spelling activity. You can also explore our site to find lots more educational crafts and activities for kids.

Share Picture Books By and About Indigenous Americans

Chyrsta Naron, an early childhood educator as well as contributor to this site, reminds us that we parents have the power to change the world through the books we expose our children to.

Chrysta quotes Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop: “Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror.”

Check out Chrysta’s post about books by and about Native Americans to create some of those mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors this year.

P.S. We’re thankful for you! Happy Thanksgiving.

By Laila Weir

Reading aloud from the start is key to setting your baby on the path to literacy. But with infants, you obviously don’t have to be reading stories per se. In fact, there don’t even have to be words on the page right at first. Early on, the idea is to capture babies’ attention and engage them with your voice, gestures, and facial expressions to spur a verbal or other response of their own. Coos, babbles, and book grabs encouraged!

As they get older, they’ll tune into the words and stories more and more, and notice the mechanics of how you crack open the book, turn the pages, and read from the front to the back. They’ll discover that books are for reading (not just chewing), that they’re read in a particular direction, and that they convey certain ideas that parents return to each time they open them. All these simple elements are actually crucial building blocks towards reading. A tip: Engaging with your baby around the book is key. See our post on how to engage kids during story time.

Ok, so hopefully you’re sold on sharing books with your little lump of sleepy cuteness. But what books should you “read” to them? Here’s the lowdown on baby books that will help you capture infants’ attention and set them out on the path towards reading.

Noise Books

Choo-choo! Moo! Baaaa. Tick-tock.

Books that focus on the noises and sounds that animals or objects make are perennially popular with babies, making them excellent candidates to capture your infant’s attention.

They also build the child’s awareness of the sounds that underpin speech. This is a crucial step in building early language—and it will eventually aid them in picking out individual sounds in words as they learn to read and write.

Noise books provide a particularly rich opportunity for adult-child interaction, as well. For example, as you read a favorite noise book to your child (probably for the umpteenth time), you may find yourself naturally prompting them to join in, even before they can really make the sounds: What does the doggy say? That’s right! Woof-woof.

This kind of interaction is gold. In fact, it’s more precious than that. Because, as it turns out, research has shown that babies acquire speech sounds by interacting with the people around them. Not by watching someone speak on TV. Not by listening to a recording of a person speaking. Only by interacting.

For all these reasons, books that feature farm animal sounds, transportation noises, and other exaggerated speech sounds of all sorts make a great addition to your baby’s bookshelf.

Bonus: If you want to dig deeper, books that emphasize the letter sounds of M, N, B, P, D, Y, W, and H are especially well adapted for building your baby’s sound awareness. Moo, baa, and bow-wow, here we come!

Nursery Rhyme Books

Rhyming (hickory dickory dock, the mouse ran up the clock) and alliteration (Peter, Peter, pumpkin-eater) are also great for developing baby’s sound awareness. Both are common features in classic and new nursery rhymes—which are also playful, lilting, frequently silly, and all-around fun.

These features make time-tested nursery rhymes, as well as modern takes on the old form, excellent choices for reading with babies. They’re also perfect vehicles for encouraging some key parent behaviors that help babies learn language: making eye contact and speaking in exaggerated and sing-song tones, as well as interacting with and responding to the baby.

Learn more in our article about the benefits of nursery rhymes.

Books with Character Names

Many baby books don’t have characters, per se, and this is fine, up to a point. But reading infants books about actual characters who have names can heighten their attention, researchers have found.

“For infants, finding books that name different characters may lead to higher-quality shared book reading experiences and result in … learning and brain development benefits,” writes psychologist Lisa S. Scott.

Scott also points out that books with named characters may lead parents to talk more with their babies when they read together. So, whether it’s Jack and Jill or Pete the Cat, look to include some stories with character names in your shared reading with baby.

Photo Books

Books with simple text and real photography are also a great bet to capture babies’ attention. Plus, studies have shown that very young kids are more likely to connect realistic images of objects with the objects themselves—thereby better learning the words associated with them—than with more abstract artistic representations or less lifelike cartoons. (Don’t worry, there will be lots of time for the pretty art later on!)

Showing babies color photos of everyday items and reading the accompanying labels expands their vocabularies in ways they find fascinating. At the same time, if you point out the word at the same time, it can help them begin to realize that the letters on the page are also associated with the item. Learning the connection between an object, a spoken word, and a written word is a key literacy skill.

Bold and High-Contrast Books

You may have heard that newborns can only see in black and white, an assumption that spawned a whole genre of black-and-white books for infants, but current analysis suggests that’s not true.

While they can’t see as well as adults at first, research indicates that infants see much like adults, according to Russell D. Hamer of Florida Atlantic University. Hamer writes that a newborn’s vision is a “rapidly developing version of adult vision, rich in pattern, contrast, and color, and that it possesses some remarkable abilities for discrimination and complex pattern recognition.”

Nevertheless, there is scientific reason to believe that bold, bright, and high-contrast patterns and shapes best draw the attention of infants during the first few months of life at least.

Face Books (including Mirror Books!)

Babies are also drawn to photos and images of other infants and children with parents or siblings, and to circles and face-like shapes in general. In fact, one study documented fetuses showing a preference for face-like shapes before they were even born!

The Global Babies series from the Global Fund for Children is a beautiful set of books featuring photos of babies from cultures around the world. There are a number of charming books in the series, including the original Global Babies, Global Baby Girls, Global Baby Boys, and more. As your baby gets older, you may want to move into books with realistic illustrations, but baby faces will remain popular with your little audience.

Books with faces also offer an opportunity to expose your infant to people from diverse backgrounds. Research into “face bias” has shown that newborns look at all faces equally, but that as they get older, babies who primarily see faces from their own race can’t recognize and remember individuals from other races as well. Choosing books featuring a diversity of faces may combat that effect. Plus, they’re fun!

Tip: Your infant’s own face will fascinate them, too, so look for baby books that include a mirror as well. These cute books also give lots of chances for interaction and giggles together.

More Tips for Reading with Baby

Keep in mind that even as you move into books with more detailed illustrations and more complicated storylines when your baby gets a little older, not all books have to have words on the page. Check out our post on how to use wordless picture books to support literacy.

When the books do have words, though, be sure to point them out. Make them a focal point (albeit a lesser one) along with the story and images. Take a look at our post on 5 Reading Aloud Tips to Get Your Child Kindergarten Ready for tips on how to do this.

Also, be sure to look for board books or fabric books. Most popular children’s books, even longer and more sophisticated stories, are available in board-book form these days, and it’s well worth it.

When your baby reaches for a book you’re reading to them, it’s a sign of engagement, and you want to encourage that! Letting them interact directly with books increases that engagement. So go ahead and let them play with their books, turn the pages, look at the pictures while riding in their stroller or car seat, and, yes, even mouth them!

Have fun looking at, playing with, chatting about … and even reading … books to your baby! Then let us know your favorite “reads” for infants in the comments.

One of the best ways we can set our young children up for kindergarten and beyond is by introducing them to the alphabet and teaching letter sounds. This may sound intimidating to busy parents without training in education, but with a few tips, it can be easy and fun. Besides teaching the letters directly, one of the easiest ways to help kids learn the ABCs and understand their purpose is snuggling together while reading simple picture books and bringing the child’s attention to the writing on the pages.

Any and all reading together will help your child learn to love books and set them on the path to becoming a reader, but pointing out the text will jump start their journey and prepare your preschooler for reading (plus help them get the most out of story time). And certain books with simple drawings (or even none) and large, noticeable print are particularly good at focusing kids’ attention on letters. This kind of book is great for helping them understand the link between the letters on the page and the words they’re hearing.

Read on for tips on how to draw attention to print while reading and a list of 10 great books that are perfect for turning your child’s attention towards letters. For more on teaching your child the ABCs (including when, how, and why to do it), see our post answering six top questions about teaching your child the alphabet.

How to Get Your Preschooler Ready for Reading

“Research findings have consistently shown that when adults call attention to print, children’s development of print knowledge accelerates,” write Laura M. Justice and Amy E. Sofka in Engaging Children with Print: Building Early Literacy Skills through Quality Read-Alouds.

In other words, when parents and educators engage children with the printed words in books, we help them form a foundational understanding of written language, which will benefit them immensely going forward in their education. A key first step is to point out and explain the use of letters in books and elsewhere (for example, letters on signs and around your neighborhood).

There are quite a few easy ways to bring attention to print and help our kids develop print awareness while we read to them:

Nonverbally:

- Point to particular words, letters, or other print features in the book

- Use a finger to follow the words as we read them

Verbally:

- Ask questions about the print (for example, Do you know this letter? or What do you think this says? while pointing to a picture of a stop sign)

- Make comments about the print (e.g. This sign says “Keep Out!” or Look! There is an A like in Avery)

- Request that the child show you features of the print (e.g. Point to an N or Show me where I should start reading)

Great Books for Preparing Preschoolers for Reading

Note: You can start drawing your child’s attention to print and letters very early on. Then, as they grow, don’t think you have to set aside baby books or early favorites. Some of your tot’s beloved board books will be perfect for teaching them their ABCs later on, with their simple words and bold text. Your child may return to them again when they start reading on their own, too.

What are your favorite books to teach little ones the ABCs? Comment below or let us know on social media!

Reading is taught, not caught. This phrase has been in circulation for decades, but it bears repeating with each new generation of parents, and it has never been more fully supported by compelling evidence. Learning to read is a complex, unnatural, years-long odyssey, and parents should bear no illusions that their kids will pick it up merely by watching other people read or being surrounded by books.

Parents are influential in helping kids navigate the twists and turns that lead to literacy. I offer five teaching tenets to carry with you. Don’t worry, there are no scripted sequences, rigid rules, or worksheets forthcoming. These are principles any parent can remember and apply with ease during long, busy days with young children. Some of the five you may know instinctually. Others may have never crossed your mind. All deserve to be hallmarks of the way we approach raising readers.

These touchstones are research-backed and parent-approved. Personally, I’ve found that returning to these principles, even now that my daughter is a strong, fluent, and independent reader, still makes a difference for her, me, and our relationship. Ultimately, they are calls to be a more patient, more responsive, and more purposeful parent in every context.

May you find the same comfort, wisdom, and practical guidance in them that I did. Take them to heart. Repeat them like mantras if you like. And remember, the sooner you embrace them, the better this journey gets.

It’s What You Say — and How You Say It

Spurring literacy development, like teaching of any kind, is about creating shared meaning between you and your little one. And that requires meeting them where they are, capturing their attention, engaging in back-and-forth exchanges, and also providing the stimulation that helps them to their next level. Parents’ actions such as asking questions vs. giving directives, introducing novel vocabulary, and arranging words and phrases in advanced ways all affect kids’ language development. But parent responsiveness plays a major role as well, for example how reliably and enthusiastically you respond to your child’s speech and actions.

As Harvard pediatrics professor Jack Shonkoff puts it, “Reciprocal and dynamic interactions . . . provide what nothing else in the world can offer — experiences that are individualized to the child’s unique personality style, that build on his or her own interests, capabilities, and initiative, that shape the child’s self-awareness, and that stimulate the child’s growth and development.”

So we must have the awareness to let a child’s age or language ability affect the content and tenor of our speech. Studies provide evidence that infants and young toddlers, for example, benefit from conversations about the here and now with us pointing and gesturing to label objects in our immediate surroundings or on the pages of books we’re reading together. And parentese is the speaking style of choice. Slower, higher pitched, and more exaggerated than typical speech, it’s been thought to advance infants’ language learning because of the ways it simplifies the structure of language and evokes a response from babies.

With older toddlers and preschoolers, we should keep examining what we’re saying and how, but update the range of things we consider. It’s no longer necessary to speak at a slow pace or nearly an octave higher than normal to aid a child’s language development. By 30 months, the variety and sophistication of parents’ word choices may have a greater influence on kids’ vocabulary growth. By 42 months, talking about things beyond the present, such as delving into memories of the past or discussions of what will happen in the future, is positively related to kids’ vocabulary skills a year later.

While it’s unnatural and unrealistic to monitor yourself all day, the thing to remember is that our words and responsiveness fuel powerful learning for kids. Set aside ten minutes a day of mindful communication, focusing on your baby, your words, and the interplay between them. Over time the focused practice will create habits that spill over into other conversations, too.

Learning Takes Time — and Space

We live in a catch-up culture, where people feel perpetually behind and forced to hustle near the finish line after being waylaid by hurdle after hurdle. This contributes to the (false) belief that we can make up in intensity what we lack in good pacing. But we can’t cram kids’ way to reading.

Ask any learning scientist about the relative merits of massing study together versus spreading it out over time. They’ll tell you that spacing between sessions boosts retention of the material. The proof of the principle (known as spaced learning, interleaving, or distributed practice) shows up all over the place. Numerous studies across the human life span, from early childhood through the senior years, have documented its power. And there’s evidence of the benefits of spaced study across a wide range of to-be-learned material, such as pictures, faces, and foreign language vocabulary and grammar.

Even learners taking CPR courses performed better if their classes were spaced out. So if you want your child to remember what you’re teaching, digging into it for ten minutes a day for three days likely will beat a half-hour deep dive. The spacing effect is among the field of psychology’s most replicated findings.

Incidentally, a study found that a bias for massed learning emerges in kids in the early elementary school years, so you’re in good company if the approach feels counterintuitive. In the preschool years, the kids were as likely to think learning something bit by bit over time was as effective as learning it in a clump. During elementary school, though, the kids started predicting that massed learning would be better at promoting memory than spaced learning.

Maybe the teaching methods employed in so many classrooms give kids (and parents) the impression that repetition, repetition, repetition in one sitting is the way knowledge sticks in memory. Want to learn your spelling words? Write them over and over again in different colored pencils. Want to practice your handwriting? Fill that page with well-formed letters.

Spacing things out may feel inefficient, but it’s more effective, more fun, and a better fit for daily life with young kids. Parents have a natural advantage in teaching more gradually, because we are with kids for hours a day over the course of years. We aren’t under intense time pressure, at least over the long term, removed as we are from the confines of a school day or school year. Nor do we have to find a way to meet the needs of twenty-five kids or more at once.

And keep in mind that the lessons we give needn’t be formal. Teaching young children often looks like talking, playing, and singing. I once ordered a home spelling program that included what felt like 50 million individual magnetic letter color-coded index cards, and scripted teaching procedures. I was so tired from separating and organizing all the materials that I never got around to working through the curriculum with my daughter.

Ultimately, conversation over a few games of prefix bingo one week taught her more about prefixes, suffixes, and units of meaning within words than the elaborate curriculum did. Why? Because that was the method I enjoyed and followed through on — the one that worked within the context of our relationship and our attention spans. She loves board games; I love talking about words. Win-win. The takeaway: do what works for you, and do it a little at a time.

The More Personal the Lesson, the Better

Helping your child learn to read requires making decision after decision. Which letters or words to teach? Which song to sing or story to tell? When making the calls, err on the side of making the lessons themselves personally meaningful for your child. Sometimes it’s as straightforward as teaching the child the letters in their name first, making up songs and stories featuring their pets, or choosing vocabulary words from their favorite books. Sometimes it’s as deep as practicing fluency by reading aloud texts that affirm and sustain a child’s cultural heritage or community.

To help conceptualize this, researchers have defined three levels of personal relevance, from mere association to usefulness to identification. When a reading lesson centers on a passage about the student’s sport of choice (say, soccer), that’s making a personal association. If you can make it clear how the lesson itself is advancing a goal the child is after (like joining wordplay with older siblings), even better. But if you can make the activity resonate with the child’s sense of self, you’re really cooking with grease. This is what’s going on when a little one named Anna sees the letter A and says, That’s my letter! She’s owning it — and identifying with it. It matters to her and she learns it quickly.

The power of personal meaning also helps explain why parents so often find that something that worked like a charm with one child falls flat with another. Kids’ associations, judgments of usefulness, and identities vary widely, even when they grow up under the same roof. Locking in on what makes your individual learner tick and facilitating resonant experiences just for them is golden.

Luckily, you have a built-in feedback mechanism for determining what’s working: your child. Even infants express preferences. A little one might reach for the same book with bold illustrations or lift-up flaps over and over again. You may also find that what gives the lesson meaning is you — your demeanor, your engagement, and your responsiveness can be tremendous motivators.

Praise the Process

You’re voluntarily reading a parenting book, so I’ll venture that you value learning and have confidence that you’ll reap some benefit from the effort you put into acting on the tips compiled here. You believe that you can know more, teach better, and make an impact. And I imagine that you want your child to feel the same sense of self-assurance as they pursue their own challenges.

One way to cultivate that can-do spirit is by cheering on their hard work, focus, and determination by name. Instead of giving generic praise like “You’re so smart,” say specifically what you loved about how they learned — not just the results. For example, if your little one is beginning to write letters: “Great job picking up the pencil and writing. I see you working to hold it in your grasp.” You’ll celebrate their work and lay the motivational track for other efforts to come.

Research by psychologist Carol Dweck and others has found evidence that when parents praise kids’ effort in the learning process — not outcomes — it impacts their kids’ belief that they can improve their ability with effort. With that growth mindset, they are more likely to think they can get smarter if they work at it, a trait that boosts learning and achievement.

In a longitudinal study, Dweck and colleagues traced the whole path of these relations, from parents uttering things like “Good job working hard” when their kids were 1 to 3 years old, to testing those same kids’ academic achievement in late elementary school. They found evidence that this process-related praise predicted a growth mindset in children, which contributed to strong performance in math and reading comprehension later on in fourth grade. The study also found evidence that parents established their praise style (more process-focused, or less so) early on. So learn how to give meaningful compliments. The positive vibes leave lasting impressions.

When in Doubt, Look It Up

This was my dad’s go-to saying when I peppered him with questions as a kid. A good reference guide, in our case a giant Webster’s dictionary that he kept on a wooden stand in his office, was always the first stop for a spelling, definition, or example. His words remain with me, reminding me how important it is to continue learning as we endeavor to teach our kids. My dad didn’t have all the answers and wasn’t afraid to learn alongside me.

When it comes to nurturing and teaching reading, we should stay curious and work to deepen our content knowledge, versus falling back on instructional methods that are more familiar than effective. For example, parents often do things like tell kids to sound out words like right, people, and sign that can’t be, well, sounded out. These words clearly don’t feature direct letter-sound matches, but our default response to any decoding question, phonetic or not, is “sound it out.” The lesson a child needs in those instances isn’t how to blend this letter sound into that one, but how the English language and its writing system work overall.

Similarly, if we decide to teach spelling, we should make it a priority to learn something about word origins and get a handle on conventional letter-sequence patterns. Having a child write a word over and over again is one method, but it’s one you’ll probably feel more comfortable letting go of as you know more about why we spell how we do. When we’re well informed about how written English works and how reading develops, we can take advantage of the countless teachable moments in everyday life.

Excerpted from Reading for Our Lives: A Literacy Action Plan from Birth to Six by Maya Payne Smart. Published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Maya Payne Smart.

Enjoyed this excerpt? Get the book!

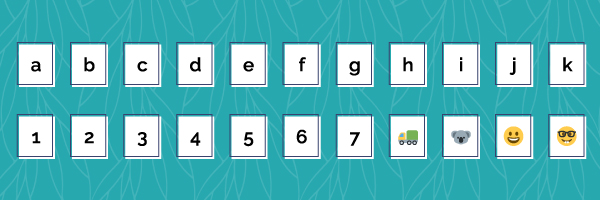

Learning that letters represent specific sounds is a major development on the road to skilled, fluent reading. But the way it happens for most kids is a slow dawning of recognition over time, as children gain experience with the 52 uppercase and lowercase letters. For this reason, it’s critical for parents to make a habit of regularly bringing kids’ attention to letter shapes, names, and sounds over their early years.

A three-year-old named Beth, for example, might know that the letter “B” says /b/ in Beth. She might recognize and point to the letter on signs or in books, and even say “that’s my letter.” But that doesn’t mean she also understands that B says /b/ universally—like in bus, banana, or bowl. And it could take weeks, months, or years for her to make connections between other letters and the sounds they make, such as knowing the letter X says /ks/ or N says /n/.

How quickly children connect written symbols to sounds comes down to exposure and practice. It matters (a lot) how frequently grownups call the kids’ attention to print and discuss specific letters and their sounds. Preschool-aged kids who see and talk about letters more will learn them faster, while kids who see them less—or not at all—will struggle later in school.

That’s why parents are the perfect candidates to teach the alphabet. As a parent, you have ample opportunity to talk about letters while going about daily life with your little one. With just your voice and the letters around you (in books and on signs, t-shirts, cereal boxes, etc.), you have all you need to help kids learn their ABCs.

Moreover, relying on school alone to teach kids their ABCs is a losing strategy. One study of 81 preschool classrooms found the teachers spent an average of just 2.77 minutes a day teaching letters. The rest of the time they focused on other important self-care, social-emotional, and pre-academic skills. Imagine how easily you could double that time at home and target the lessons to your child’s level.

The Best Way to Teach the Alphabet

So how should you teach the alphabet? The best way to start is with some simple, direct teaching. After that, it’s a question of practice and repetition, which can be easily accomplished through play.

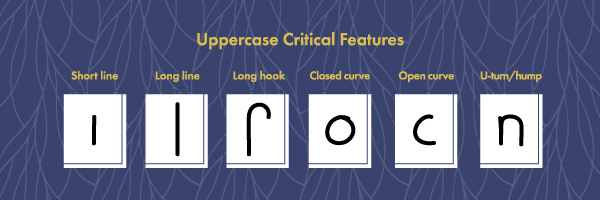

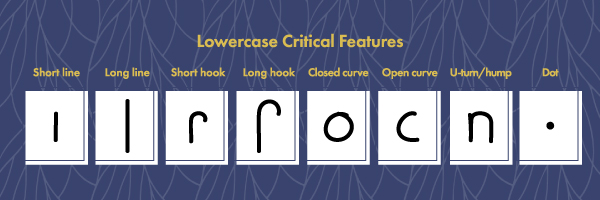

To begin, just draw your child’s attention to letters and their component parts. Critical features to point out within letters include short and long lines, open and closed curves, hooks, humps, and dots. Bonus points if you refer to these letter parts consistently (e.g. short line, long line, hook, curve) so that kids grasp that they’re used to form various letters. For example, you can point out the “long lines” that appear in A, B, and D, as well as the curves in C and G. Similarly, you can help kids notice that the features can vary in orientation (horizontal, vertical, diagonal), size (height, width), overlap, and more. Paying attention to these features helps with both letter recognition and letter formation (writing).

Research suggests that elements like where curves and lines terminate and intersect help people distinguish among letters. When children begin trying to write, they engage more actively with the shapes of different letters and pay greater attention to their distinctive features (e.g. curves, humps, and dots). But even before kids have the motor skills needed to write, you can introduce them to forming letters by giving them laminated letter-part cutouts to assemble into letters.

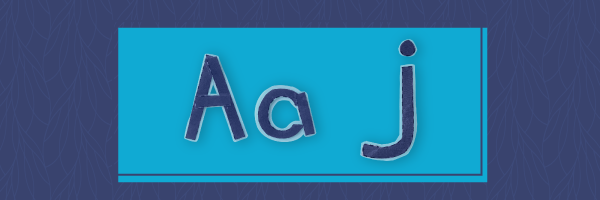

For example, a capital A would be constructed from two long lines and one short line. A lowercase j would feature a dot and a long hook.

There are countless opportunities every day for you to point out letters in the books you read to your child or on signs and labels in your home or neighborhood. But you can also just whip out a sheet of paper or index card, write a letter on it, and talk to your child about it.

How to Talk about Letter Shapes, Names, and Sounds

It’s a surprisingly powerful literacy lesson just to say something as simple as This is the letter T. T says /t/ like in taco. T is made from one short line (trace across the top of the letter) and one long line (trace across the vertical line). In a matter of seconds, you’ve brought your child’s attention to a letter, given its name, highlighted its main sound, and traced its shape.

In fact, talking about letters may be one of the easiest and highest return-on-investment activities parents can do. Over time, these light touches will stick the ABCs in your child’s memory. You’ll build their knowledge of English’s 26 letters, the ways they combine to form 44 different speech sounds, and the 52 different ways we write them (uppercase and lowercase). And you’ll pave the way for them to sound out hundreds of thousands of words. It’s no wonder that letter knowledge at kindergarten entry is a significant predictor of reading skills down the road.

You can describe the lines and curves within the visual forms of letters, comparing and contrasting the shapes of different letters, for example comparing a lowercase “b” and “d.” You can write a “c” and draw a cat next to it, pointing out that the word begins with the /k/ sound. And so on.

I’m highlighting this kind of direct, straight-forward teaching of letters (individually, in isolation, and outside of words) because sometimes our preconceptions about what’s “natural,” “meaningful,” and “enjoyable” in young children’s learning get in the way of doing what’s effective and efficient.

A review of four randomized control trials of letter instruction for three- and four-year olds found that teaching letters on their own was more effective than teaching them while reading a book or within the context of words or names—and it was fun, engaging, and motivating to boot. Think about it: Letter lessons delivered during storybook reading have to compete with all the wonderful images and stories unfolding on the books’ pages.

That’s not to say that there’s no benefit to teaching letters within the context of books or everyday signage. In fact, you absolutely should do that, too. It’s just to say that it’s not the first or only way you should be teaching letters. It’s critical to teach literacy skills in meaningful contexts (in this case, within words) as well as in isolation. How else would kids learn what letters are for and how they connect with sounds and meaning? There are some books with large, bold letters and sparse illustrations that are perfect for drawing attention to print. They’re entertaining for kids and provide valuable prompts for parents to remember to talk about print. (More on this below.)

The point is: It’s best to teach letters in and out of context. Giving a specific lesson on a specific skill or a single letter isn’t tantamount to “drill and kill”—provided you keep it brief, light, playful, and responsive to your child. Key elements of education are practice, repetition, and “retrieval”—which is a fancy way of saying bringing knowledge up from memory—even with three-year-olds. So go ahead, give some five-minute direct letter lessons now and then.

It makes sense developmentally to start with uppercase printed letters, because they’re easier for kids to recognize than lowercase and handwritten letters.

A Simple Letter Lesson to Try

Just remember to keep it light and easy. You can create impactful letter experiences with young children in ten minutes or less. A home letter lesson, adapted from this instructional progression idea, might look like doing the following:

- Pick a letter.

- Write it on a piece of paper, say its name, and most common sound. This is the letter Z. Z says /z/.

- Describe its lines, curves and other distinctive features while pointing to or tracing them. Z is made of three lines. Two short and one long.

- Ask the child to trace and describe the featured letter parts one by one (e.g. lines, curves, dots). Can you trace the lines of the Z with your finger?

- Ask the child to write the key letter parts on whatever surface and whatever materials are handy (e.g. pencil on paper, shaving cream on the side of the bathtub, on the sidewalk with chalk). Can you draw one long and two short lines on this piece of paper?

- Ask the child to combine the features to form the letter. (Or, if their motor skills aren’t there yet, ask them to assemble the letter by combining letter-part cutouts.) Can you write a Z made of three lines?

This approach gives the child a bit of runway as they approach writing the letter. It gives them repeated opportunities to see the letter’s visual form while hearing its name and it breaks down the component features needed to write or build the letter.

How Kids Learn to Recognize and Distinguish Among Letters

As readers ourselves, parents often fail to grasp what a leap it is even to see letters as distinct from other images and graphics in print. To know an O from a circle or an H from a stick figure is the result of a long learning process, a slow-growing awareness of print and its properties. At first, pictures, letters, and numbers are all a bunch of 2D marks to be deciphered.

Children begin to be able to distinguish different things they see as infants. However, it takes years for them to develop the ability to differentiate letters from one another and from other letter-like forms. After all, all letters look very, very similar to one another when taken in the context of most other “objects” kids are learning to distinguish visually.

Eventually, they come to easily distinguish letters from numbers and other visual forms with letter-like shapes. They also tend to learn printed uppercase letters before lowercase letters and handwritten letters. As kids get older and gain more and more experience with letters in print, handwriting, cursive, and various fonts, their ability to discern letter variations and distortions grows. That is, they come to know that all of the following, despite different cases and fonts, are As.

The sequence of letter-learning varies among children but, generally speaking, kids learn:

- Letters in their own names before other letters

- Uppercase letters before lowercase letters

- Printed letters before handwritten letters

- Letters early in the alphabet (A, B, C) before letters later in the alphabet

- The sounds for letters when the letter name gives a clue (“dee” for duck) before sounds for letters whose names don’t contain the letter sound (“double-u” for Wednesday)

- Sounds for letters with a single sound (e.g. /b/ for B) before sounds for letters with multiple sounds (e.g. /k/ and /s/ for C)

Teach & Practice the ABCs Through Play

As a parent teaching your child the alphabet, there are many different ways to deliver the letter lessons described above. You can point out letters as you play with alphabet blocks, write them for your child in glue or glitter, form them from playdough, and so on. Mixing the learning in to playtime with your child will keep it fun and engaging for them (and you).

Once your child is familiar with some letter names, shapes, and sounds, practice and repetition become especially important. It takes years to commit all those to memory, so finding fun games and crafts to reinforce the learning is powerful. Below are links to numerous activities you can do with your child to help them learn the names, shapes, and sounds of the ABCs.

Letter Name Games

Sure, you could hold up a card with a letter on it to find out what letter names your child knows. But if you call it a game of War and have them play against you, suddenly it’s transformed into something more lively and engaging. The same goes for naming letters on a board game, hopscotch squares, a soccer ball, or a scavenger hunt. Some letter-name practice is just more fun as your kids work to learn to correctly identify all 52 different uppercase and lowercase letters.

- Alphabet Game of War

- DIY Alphabet Board Game

- DIY Alphabet Fishing

- Alphabet Soccer

- Alphabet Hopscotch

- Outdoor ABC Scavenger Hunt

Letter Shape Activities

Nothing helps a child spend sustained time thinking about letter shapes better than an activity that gives them a chance to form a letter themselves. It also gets them in tune with the lines, curves, and intersections of letters even before they have the fine motor skills to write them with a skinny pencil. Give any or all of these activities a try to create fun time learning letters.

Letter Sound Play

I love The Name Game (Bananafana fofana fi fi fofana banana) for giving kids practice manipulating the sounds within words, attuning their ears to the different sounds that make up language—a crucial skill for later reading, writing, and spelling. But little ones also need to learn which sounds map to which written letters, and parents could use a slew of activities to provide that critical practice lightly over time.

- Wheel of Phonics

- Sound Search Game

- Pretend Alphabet Soup

- Alphabet Bingo

- All-Day Alphabet Scavenger Hunt

- Outdoor ABC Scavenger Hunt

- Alphabet Hopscotch

- Alphabet Soccer

- DIY Alphabet Board Game

- Alphabet Game of War

Seasonal Letter Fun

Getting your child’s attention is half the battle with anything you want to teach. And sometimes a seasonal hook is just the way to get your child in the letter-learning spirit. Here are some Thanksgiving, Halloween, Christmas, and Valentine’s Day activities to infuse a little learning into the holidays:

- DIY Turkey Letter Matching Game for Thanksgiving

- Christmas Alphabet Flipbook

- Halloween Alphabet Spinner

- Valentine’s Day ABC Memory Game

Tools for Teaching the Alphabet at Home

You can teach your child the letters of the alphabet with a little knowledge, a dab of confidence, your voice, and your pointer finger, for example using the scripts above. But using some external tools can help make the necessary practice and repetition more fun for them—and for you. Index cards, letter tiles, and alphabet books top my list of go-to tools, but there are lots of resources you can use to reinforce letter learning. Draw from the list below, and click on each tool to learn more and get inspiration for how to use it:

- Playdough

- Stacking Blocks

- Index Cards

- Letter tiles

- Comic Sans

- Craft Sticks

- Letter Tracing Sheets (free printable)

- Alphabet Books

Teaching with Alphabet Books

You can and should teach with whatever letters you find in your everyday environment, from the grocery store to the bus stop. But carefully curated books also create great opportunities to bring kids’ attention to print. And well-chosen alphabet books, in particular, can make letter teaching a snap for parents. Displaying quality ABC books in your home will create wonderful prompts to spend much-needed time engaged in letter talk with your child.

Numerous studies suggest that alphabet books prompt parents to talk about words, letters, and the writing system more than other kinds of picture books. While reading ABC books, parents naturally reference letters, count letters, separate words into individual sounds (also known as phonemes), and ask kids to do the same. All of this letter talk helps kids understand that printed text represents spoken language—and it builds their bank of letters and words they know.

When reading typical picture books, by contrast, parents are less likely to even draw kids’ attention to the print, much less to dig into the form, function, and features of written language. You’re understandably busy reading the story and talking about the book’s plot, illustrations, or connections between the story and the child’s life.

Don’t get me wrong: There is tremendous value to reading all genres of picture books, and those other kinds of read-alouds and conversations are crucial for developing vocabulary, comprehension, and book love. It’s just that when your aim is teaching letters, alphabet books are a wonderful choice. They make it easy to stay on task, provided you choose the right kind of ABC books.

Alphabet Teaching FAQs

At what age do kids need to know the alphabet, and when should parents start teaching them?

Kids should recognize all uppercase and lowercase letters of the alphabet by the end of kindergarten, according to the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts. So the question is: What should parents do when their kids are infants, toddlers, or preschoolers to help them meet that expectation? When should letter instruction begin? How should it progress as children grow?

If books and reading aloud are a part of your family life beginning in your child’s infancy, your child may begin to gain awareness of printed letters before their second birthday. For example, the Texas Infant, Toddler, and Three-Year-Old Early Learning Guidelines state that toddlers (18-36 months old) might recognize some letters with help, such as their own first initial.

“Help” is an adult drawing attention to the child’s name, for example, showing a monogrammed blanket and saying “Z says /z/. Z-O-R-A says Zora,” as they point to each letter in turn. Helping your child make the connection that a printed shape corresponds with a particular sound can be just as simple as repeating short sentences like that now and then—again and again over the days, weeks, and months of early childhood.

After three years old, kids’ letter-learning capacity noticeably expands. Between 36 and 48 months old, children might identify some letters, know the sounds some of them make, write letter-like forms, and even grasp that letters combine to make words, the Texas guidelines say. Some research suggests that three-year-olds can learn as much about the alphabet as four-year-olds. And about half of four-year-olds recognize their own first initial and can name some printed letters. Of course, fulfilling that potential depends on the visual experiences with print, and conversations around print, that young children have with the adults in their lives. So ramp up your letter teaching when your child is about three.

Formal letter instruction typically accelerates in the preschool and pre-K years. But the federal and state standards that early educators use to guide instruction vary widely in terms of how many letters they say kids need to know and by when. For example, South Dakota’s benchmarks expect that an older preschooler (45 to 60+ months) can “recognize and name at least half of both upper and lowercase letters of the alphabet.” In Texas benchmarks, by contrast, a child is considered on track at the end of preschool if they can “name at least 20 upper and at least 20 lowercase letters in the language of instruction.”

I say, aim to give your child rich lessons in letter names before kindergarten, because you don’t know which letters your particular child will pick up right away and which will take them more time to learn. Your child may even master them all, paving the way for more advanced literacy lessons come kindergarten.

Is it pushing kids too far, too fast to teach them the ABCs so young?

No. The timing of letter-learning matters because the number of letter names kids know at kindergarten entry predicts their later success in reading and spelling. And that’s independent of the child’s age, socioeconomic status, IQ, and other early literacy skills, according to the National Early Literacy Panel.

Evidence supports aiming for kids to learn 18 uppercase letter names and 15 lowercase letter names by kindergarten, say researchers who study the relationship between preschool learning and later academic outcomes. In other words, kids are fully capable of knowing that many letters at kindergarten entry (with our help), and those who do are more likely to succeed in the classroom.

Some parents may object to directly teaching letters to three-year-olds—and to the notion that kids should know the whole alphabet by the end of kindergarten—on the grounds that they learned their letters later in life, and they read fine.